Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

Guest

Field Note

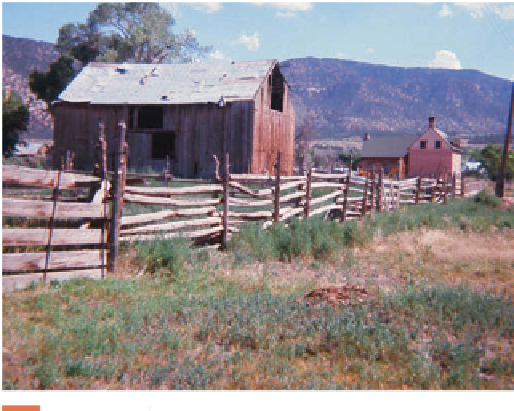

Paragonah, Utah

I took this photograph in the village of Paragonah, Utah, in

1969, and it still reminds me that fi eldwork is both an art and

a science. People who know the American West well may

immediately recognize this as a scene from “Mormon Coun-

try,” but their recognition is based primarily on their impres-

sions of the place. “It is something about the way the scene

looks,” they may say, or “it feels like a Mormon village because

of the way the barn and the house sit at the base of those arid

bluffs.” These are general impressions, but how can one prove

that it is a Mormon scene? That is where the science of fi eld-

work comes into play. Much like a detective investigating a

crime scene, or a journalist writing an accurate story, the

geographer looks for proof. In this scene, we can spot several

of the ten elements that comprise the Mormon landscape. First, this farmstead is not separate from the village, but part of

it—just a block off of Main Street, in fact.

Figure 4.28

Paragonah, Utah.

Photo taken in 1969.

Next we can spot that central-hall home made out of brick; then there is that simple, unpainted gabled-roof barn; and

lastly the weedy edge of a very wide street says Mormon Country. Those are just four clues suggesting that pragmatic Mor-

mons created this cultural landscape, and other fi eldwork soon confi rmed that all ten elements were present here in Par-

agonah. Like this 40-year old photo, which shows some signs of age, the scene here did not remain unchanged. In Paragonah

and other Mormon villages, many old buildings have been torn down, streets paved, and the landscape “cleaned up”—a

reminder that time and place (which is to say history and geography) are inseparable.

Credit: Richard Francaviglia, Geo.Graphic Designs, Salem, Oregon

United States and Canada, including symmetrical

brick houses that look more similar to houses from the

East Coast than to other pioneer houses, wide streets

that run due north-south and east-west, ditches for

irrigation, poplar trees for shade, bishops storehouses

for storing food and necessities for the poor, and

unpainted fences. Because the early Mormons were

farmers and were clustered together in villages, each

block in the town was quite large, allowing for one-

acre city lots where a farmer could keep livestock and

other farming supplies in town. The streets were wide

so that farmers could easily turn a cart and horses on

the town's streets.

The morphology (that is, the size and shape of a

place's buildings, streets, and infrastructure) of a

Mormon village tells us a lot, and so too, can the shape

and size of a local culture's housing. In Malaysia, the

Iban, an indigenous people, live along the Sarawak

River in the Borneo region of Malaysia. Each long

house is home to an extended family of up to 200 people.

The family and the long house function as a community,

sharing the rice farmed by the family, supporting each

other through frequent flooding of the river (the

houses are built on stilts), and working together on the

porch that stretches the length of the house. The rice

paddies surrounding each long house are a familiar

shape and form throughout Southeast Asia, but the

Iban long house tells you that you are experiencing a

different kind of place-one that reflects a unique local

culture.

Focus on the cultural landscape of your college campus.

Think about the concept of placelessness. Determine

whether your campus is a “placeless place” or whether the

cultural landscape of your college refl ects the unique iden-

tity of the place. Imagine you are hired to build a new stu-

dent union on your campus. How could you design the

building to refl ect the uniqueness of your college?

142