Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

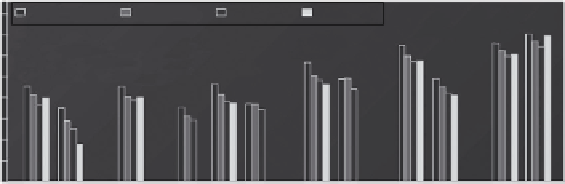

S

ã

o Paulo

100,000,000

Mexico City

Santiago

New York

Restricted

activities

Acute

morbidity

10,000,000

1,000,000

100,000

10,000

1,000

100

10

1

Other

medical visits

Hospital

admissions

Chronic

morbidity

Mortality

FIGURE 13.5

Estimated potential human health beneits from reductions in air pollution associated with

implementing GHG mitigation measures in four cities (2001-2020). (From Cifuentes, L. et al.,

Science

,

293(5533), 1257, 2001b.)

assessments of GHG mitigation policies on public health have been produced for Canada (Last et al.,

1988) and selected energy sectors in China (Wang and Smith, 1999; Cao et al., 2008), under dif-

fering baseline assumptions. A synthesis of research on co-beneits and climate change policies in

China concluded that China's Clean Development Mechanism potentially could save 3,000-40,000

lives annually through co-beneits of improved air pollution (Vennemo et al., 2006). Several studies

investigated the links between regional air pollution and climate policy in Europe (Working Group

on Public Health and Fossil Fuel Combustion, 1997; Alcamo, 2002; van Harmelen et al., 2002).

13.5.3 M

onetary

v

aluations

oF

M

itigation

c

o

-b

eneFits

To help decision makers assess policies with a wide array of health consequences, outcomes are often

converted into comparable formats. One approach is to convert health outcomes into economic terms

to allow direct comparison of costs and beneits. There are several common approaches for eco-

nomic valuation of averted health consequences (step 3 of Figure 13.4): cost of illness (COI); human

capital; willingness to pay (WTP) methods; and quality-adjusted life year (QALY) approaches. The

COI method totals medical and other out-of-pocket expenditures and has been used for acute and

chronic health endpoints. For instance, separate models of cancer progression and respiratory disease

were used to estimate medical costs from these diseases over one's lifetime (Hartunian et al., 1981).

However, early attempts to value mortality risk reductions applied the human capital approach, which

estimates the “value of life” as lost productivity. This method is generally recognized as problematic

and not based on modern welfare economics, where preferences for reducing death risks are not cap-

tured. Another limitation is incorporation of racial- or gender-based discrimination in wages. This

method assigns value based solely on income, without regard to social value, so unpaid positions such

as homemaker and lower-paid positions such as social worker receive lower values. Because data are

often available for superior alternatives, this approach is rarely used in health beneit studies. WTP

generates estimates of preferences for improved health that meet the theoretical requirements of neo-

classical welfare economics, by aiming to measure the monetary amount persons would willingly

sacriice to avoid negative health outcomes. Complications arise in analysis and interpretation because

changes in environmental quality or health often will themselves change the real income (utility)

distribution of society. A valuation procedure that sums individual WTP does not capture individual

preferences about changes in income distribution. Another complication is that the value of avoided

health risk may differ by type of health event and age. The QALY approach attempts to account for the

quality of life lost by adjusting for time “lost” from disease or death, but these estimates may be very

insensitive to different severities and types of acute morbidity (Miller, 2006).

Search WWH ::

Custom Search