Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

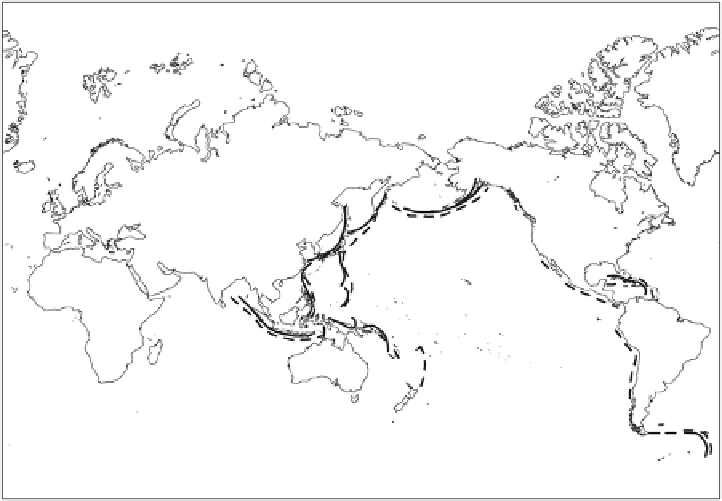

FIGURE 2.10

Distribution of island arcs (solid lines) and deep-sea trenches (dashed lines). Both phe-

nomena occur mostly around the Pacific, a closing ocean. (Adapted from various sources.)

Plate tectonics provides a broad and unifying framework into which virtually all as-

pects of Earth science fit. Although details are still being added, especially in the more

complex and older continental areas, the theory explains the movement of continents,

as well as such formerly perplexing problems as the youthfulness of the bottoms of the

ocean basins. The origin of the oceans has long been a great enigma: They are thought

to have formed soon after initial

accretion,

when the crust had cooled enough to allow

liquid water. The Earth is over 4 billion years old, yet the sea-floor rocks are less than

180 million years old. This disparity can be explained easily in plate tectonic theory.

New sea-floor crust is continually produced at the mid-ocean ridges and destroyed at

the subduction zones; as a result, it can never be very old. The continents, on the oth-

er hand, can be broken apart and reassembled in various ways as continental plates

are rifted apart or sutured together in collisions, and because of their low density they

are not subducted easily; the basic amount of continental material stays the same or

increases through time. Erosion may wear down the land and transport the low-density

sediments to the sea, but much of this material is reconstituted by being carried down

subduction zones, melted, and then rising up as igneous intrusions and added to exist-

ing continental masses through mountain building. Continents thus display accretion of

younger material and active tectonism at their edges, whereas their interiors are com-

monly older and more stable.

Mountain Building and Plate Tectonics

Search WWH ::

Custom Search