Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

refractive index), then the light will be entirely coupled into the second guide

after a characteristic length referred to as the coupling length. This coupling

length value is definable in terms of wavelength, mode confinement, and

interwaveguide separation [42]. If the indices of refraction of the two guides

are slightly different, the net coupling may be quite small, so that application

of a voltage across the electrodes shown in Figure 2.18 will change the indi-

ces of refraction and, therefore, the propagation velocities, thus destroying

the phase matching. This determines which port (3 or 4 in Figure 2.18) the

light will be coupled into after a length

L

. For directional couplers, switch-

ing speeds as fast as 1 ps are possible; however, to accomplish this device,

lengths must be on the order of 1 mm. Although not a fabrication problem

it is known that the shorter the device length, the greater the applied volt-

age must be in order to obtain optical isolation [43]. For device lengths of

10 mm, control voltages of 2-8 V are required dependent on the wavelength.

For 1 mm devices, voltages of 10-30 V are required. Two other examples of

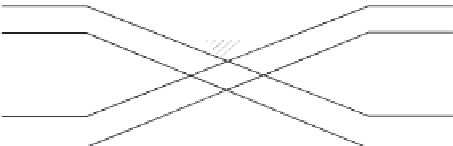

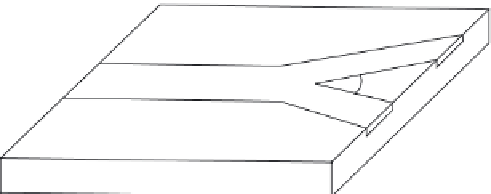

directional couplers are the X switch and the merged directional coupler

(Figures 2.19 and 2.20) [44]. Again a applied voltage will cause a change in

refractive index to occur causing changes in the coupling ratio. Switching

characteristics are direct functions of device length and switching voltage as

with previous devices.

v

L

1

3

α

2

4

∆

n

2∆

n

FIGURE 2.19

X-switch.

2

v

3

1

Θ

v

2

3

FIGURE 2.20

Y junction switch.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search