Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

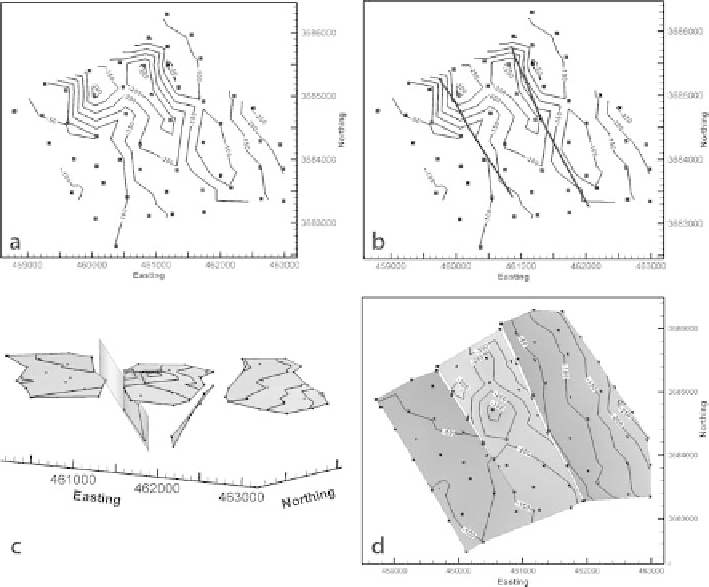

Fig. 8.6.

Example of procedure for fault interpretation applied to top of Gwin coal cycle, Deerlick Creek

coalbed methane field, Alabama (based on data in Groshong et al. 2003b). Contour interval is 50 ft,

squares

show well locations.

a

Top of the Gwin contoured without faults.

b

Top of the Gwin showing approximate

fault traces.

c

3-D oblique view of top Gwin broken into separate blocks at fault traces and re-contoured.

d

Top of Gwin re-mapped to fit the faults. Additional

squares

are points defining HW and FW cutoff lines

footwall blocks (Fig. 8.6c) and finally re-mapped to join the marker surface to the fault

planes (Fig. 8.6d). The final re-mapping requires contouring up to and across the fault

planes and must honor the known fault separations. Locating the faults, projecting

beds to the fault surface, and contouring up to and across a fault will be discussed next.

8.3.1

Locating the Fault

In mapping a single marker surface with data from wells, the exact location of a fault

is usually uncertain. Closely spaced, parallel contours on the marker surface provide

a clue to the presence of a fault but do not necessarily give an accurate location. For

example, the traces of the faults in Fig. 8.6b are in regions of closely spaced contours

but do not follow the contours. Furthermore, it is rare for a well to cut a fault exactly at the

marker horizon being mapped and so direct evidence of the fault location in the marker

horizon is usually absent. All fault cuts at any stratigraphic level that can be correlated