Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

variety or subspecies (

Homo

sapiens neanderthalensis

), whereas

others consider them as a separate

species (

Homo neanderthalensis

).

In any case, their name comes

from the fi rst specimens found in

1856 in the Neander Valley near

Düsseldorf, Germany.

The most notable differ-

ence between Neanderthals and

present-day humans is in the skull.

Neanderthal skulls were long and

low, with heavy brow ridges, a pro-

jecting mouth, and a weak, reced-

ing chin. Their brain was slightly

larger, on average, than our own

and somewhat differently shaped.

The Neanderthal body was more

massive and heavily muscled than

ours, with rather short lower limbs,

much like those of other cold-

adapted people of today.

Based on specimens from

more than 100 sites, we now

know that Neanderthals were

not much different from us, only

more robust. Europe's Neander-

thals were the fi rst humans to move into truly cold climates,

enduring miserably long winters and short summers as they

pushed north into tundra country. Their remains are found

chiefl y in caves and hut-like rock shelters, which also contain

◗

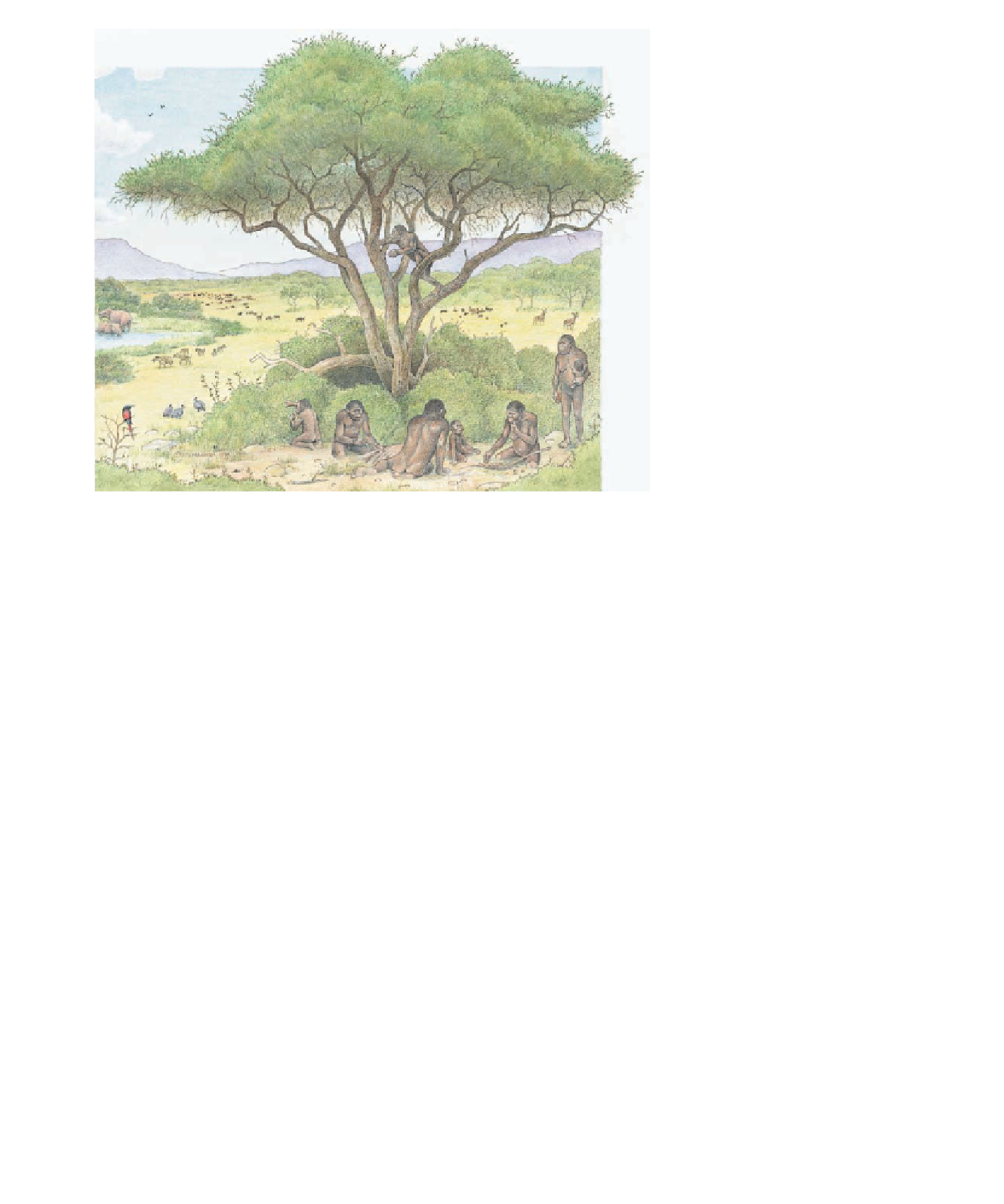

Figure 23.33

African Pliocene Landscape Recreation of a Pliocene landscape showing

members of

Australopithecus afarensis

gathering and eating various fruits and seeds.

Perhaps the most famous of all fossil humans are the

Neanderthals

, who inhabited Europe and the Near East

from about 200,000 to 30,000 years ago (

Figure 23.37).

Some paleoanthropologists regard the Neanderthals as a

◗

◗

Figure 23.35

Australopithecus robustus

The skull of

Australopithecus robustus

had a massive jaw, powerful chewing

muscles, and large, broad, fl at chewing teeth apparently used for

grinding up coarse plant food.

◗

Figure 23.34

Australopithecus africanus

A reconstruction of

the skull of

Australopithecus africanus

. This skull, known as that of

the Taung child, was discovered by Raymond Dart in South Africa in

1924 and marks the beginning of modern paleoanthropology.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search