Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

is an eroded laccolith. Another prominent volcanic feature is

Shiprock in New Mexico, a volcanic neck that dates from the

Late Oligocene.

Pleistocene glacial deposits are present in the northern

part of the Central Lowlands, as well as in the northern Great

Plains; however, during most of the Cenozoic Era, nearly all

of the Central Lowlands was an area of active erosion rather

than deposition.

a plain across which streams fl owed eastward to the ocean.

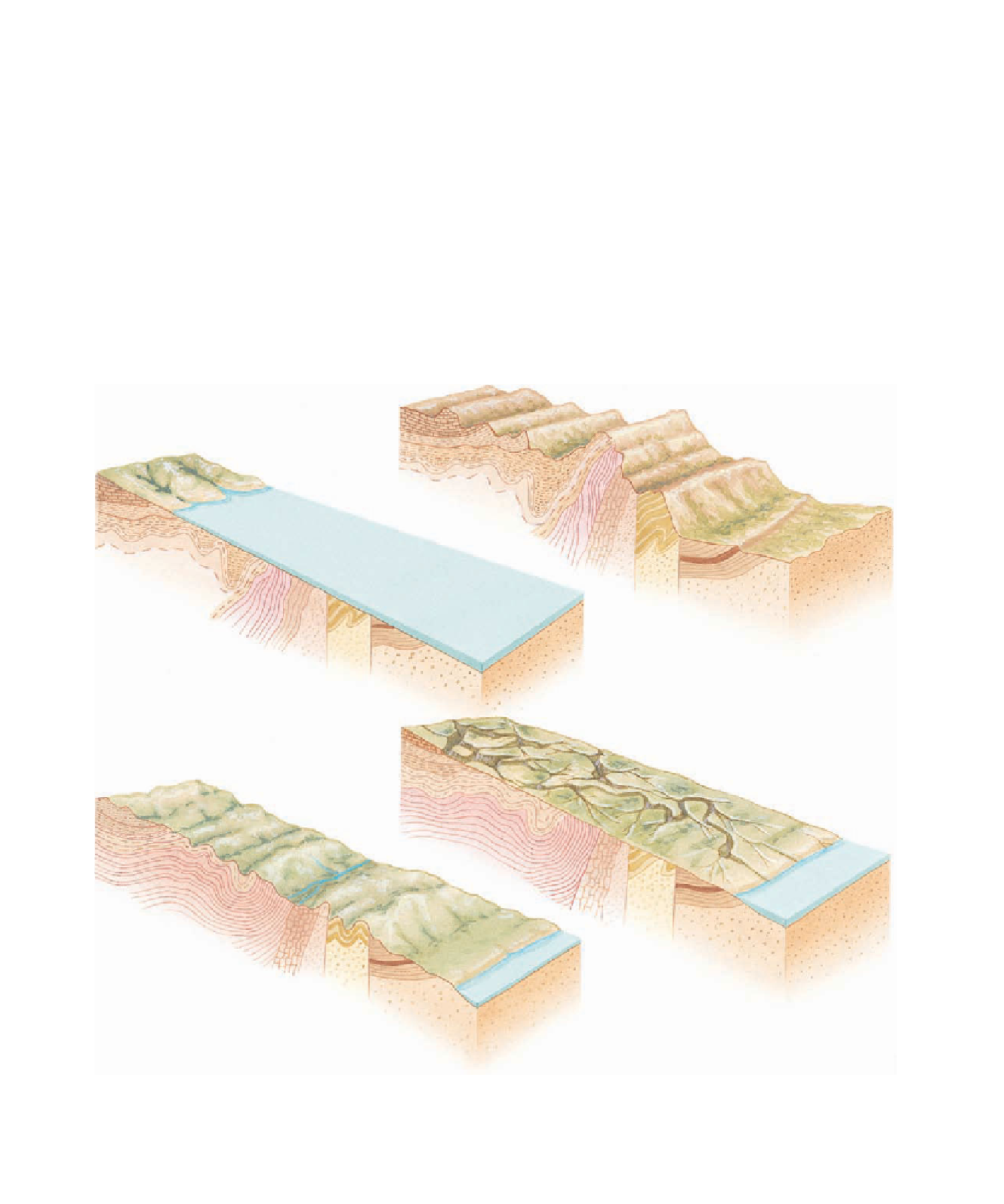

The present distinctive aspect of the Appalachian Moun-

tains developed as a result of Cenozoic uplift and erosion

(

Figure 23.11). As uplift proceeded, upturned resistant

rocks formed northeast-southwest trending ridges with in-

tervening valleys eroding into less resistant rocks. The pre-

existing streams eroded downward while uplift took place,

were superposed on resistant rocks, and cut large canyons

across the ridges, forming

water gaps

, deep passes through

which streams fl ow, and

wind gaps,

which are water gaps no

longer containing streams.

Erosion surfaces at different elevations in the Appala-

chians are a source of continuing debate among geologists.

Some are convinced that these more or less planar surfaces

show evidence of uplift followed by extensive erosion and

then renewed uplift and another cycle of erosion. Others

◗

Mountains

The Applachian Mountain region has a history of deforma-

tion during the Proterozoic and Paleozoic, and during the

Mesozoic, the region experienced block-faulting. By the end

of the Mesozoic, though, the mountains had been eroded to

Late Triassic

Cretaceous

Cenozoic

Recent

◗

Figure 23.11

Evolution of the Present Topography of the Appalachian Mountains Although these

mountains have a long history, their present topographic expression resulted mainly from Cenozoic

uplift and erosion.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search