Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

Reliable earthquake prediction is

still in the future, but can anything

be done to control or at least partly

control earthquakes? Because of

the tremendous energy involved,

it seems unlikely that humans will

ever be able to prevent earthquakes.

However, it may be possible to grad-

ually release the energy stored in

rocks, thus decreasing the probabil-

ity of a large earthquake and exten-

sive damage.

During the early- to mid-1960s,

Denver, Colorado, experienced

numerous small earthquakes. This

was surprising because Denver had

not been prone to earthquakes in

the past. In 1962, geologist David

M. Evans suggested that Denver's

earthquakes were directly related to

the injection of contaminated waste-

water into a disposal well 3674 m

deep at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal,

northeast of Denver (

Epicenter of

Loma Prieta

earthquake

San Francisco

fa

ult

San Juan

Bautista

Parkfield

Los Angeles

Southern

Santa Cruz

Mountains gap

San Francisco

Peninsula gap

Parkfield

gap

0

5

10

0

100

200

300

400

0

5

10

Figure 8.20a).

The U.S. Army initially denied that a

connection existed, but a USGS study

concluded that the pumping of waste

fl uids into fractured rocks beneath the

disposal well decreased the friction

on opposite sides of fractures and, in

effect, lubricated them so that move-

ment occurred, causing the earth-

quakes that Denver experienced.

Figure 8.20b shows the relation-

ship between the average number of earthquakes in Denver

per month and the average amount of contaminated fl uids

injected into the disposal well per month. Obviously, a high

degree of correlation between the two exists, and the corre-

lation is particularly convincing considering that during the

time when no waste fl uids were injected, earthquake activity

decreased dramatically.

Experiments conducted in 1969 at an abandoned oil

field near Rangely, Colorado, confirmed the arsenal hy-

pothesis. Water was pumped into and out of abandoned oil

wells, the pore-water pressure in these wells was measured,

and seismographs were installed in the area to measure any

seismic activity. Monitoring showed that small earthquakes

were occurring in the area when fl uids were injected and that

earthquake activity declined when fl uids were pumped out.

What the geologists were doing was starting and stopping

earthquakes at will, and the relationship between pore-water

pressures and earthquakes was established.

Based on these results, some geologists have proposed

that fluids be pumped into the locked segments or seis-

mic gaps of active faults to cause small- to moderate-sized

◗

0

100

200

300

400

Distance (km)

◗

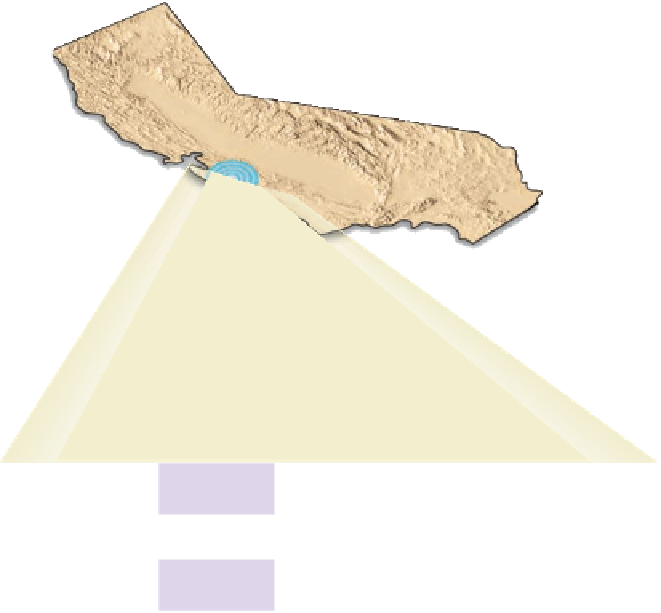

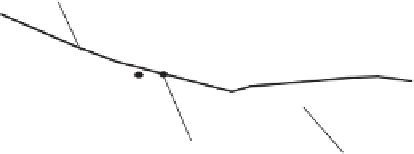

Figure 8.19

Earthquake Precursors Seismic gaps are one type of earthquake precursor that

can indicate a potential earthquake in the future. Seismic gaps are regions along a fault that

are locked; that is, they are not moving and releasing energy. Three seismic gaps are evident in

this cross section along the San Andreas fault from north of San Francisco to south of Parkfi eld.

The fi rst is between San Francisco and Portola Valley, the second near Loma Prieta Mountain,

and the third is southeast of Parkfi eld. The top section shows the epicenters of earthquakes

between January 1969 and July 1989. The bottom section shows the southern Santa Cruz

Mountains gap after it was fi lled by the October 17, 1989, Loma Prieta earthquake (open circle)

and its aftershocks.

Their earthquake prediction program was initiated soon after

two large earthquakes occurred at Xingtai (300 km southwest

of Beijing) in 1966. This program includes extensive study

and monitoring of all possible earthquake precursors. In ad-

dition, the Chinese emphasize changes in phenomena that

can be observed and heard without the use of sophisticated

instruments, such as observing changes in animal behavior

or changes in well water levels. They successfully predicted

the 1975 Haicheng earthquake, but failed to predict the

devastating 1976 Tangshan earthquake that killed at least

242,000 people.

Progress is being made toward dependable, accurate

earthquake predictions, and studies are underway to assess

public reactions to long-, medium-, and short-term earth-

quake warnings. However, unless short-term warnings are

actually followed by an earthquake, most people will proba-

bly ignore the warnings as they frequently do now for hurri-

canes, tornadoes, and tsunami. Perhaps the best we can hope

for is that people in seismically active areas will take mea-

sures to minimize their risk from the next major earthquake

(Table 8.5).

Search WWH ::

Custom Search