Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

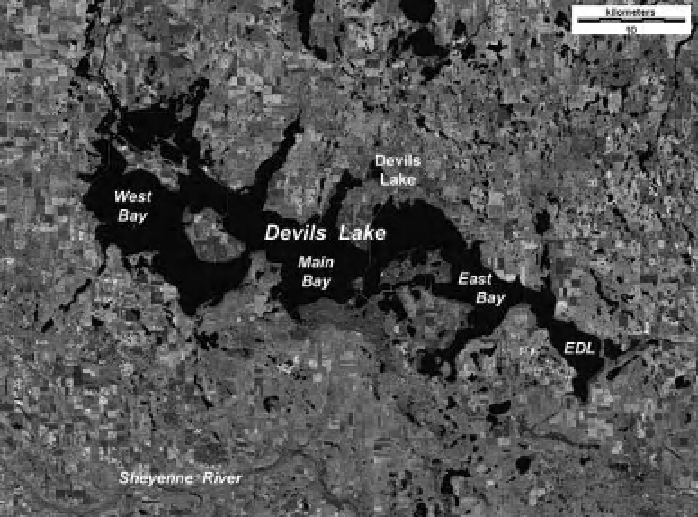

Figure 8-26.

Devils Lake vicinity, northeastern North Dakota, United States. Landsat TM band 5 (mid-infrared)

satellite image showing expanded extent of lakes, 8 September 2000. EDL

=

East Devils Lake, which was formerly a

separate lake (see Fig. 8-28). Image from NASA; processing by J.S. Aber.

climatic cooling

-

a positive feedback relation-

ship. A shift toward warmer, drier climate would

have the opposite consequence, again a positive

feedback situation. However, neither climate nor

wetlands behave in such simplistic ways. Con-

sider, for example, the northern Great Plains of

the United States. Climate has become gradually

warmer during the past half century in the

Dakotas and Minnesota. However, precipitation

has also increased, with major consequences for

wetlands, as demonstrated by frequent l ooding

of the Red River of the North and expansion of

Devils Lake in the northeast of North Dakota

(Fig. 8-26).

Devils Lake is a system of connected, large

lake basins scooped out during the last glaciation

of the region, some 14,000 to 12,000 years ago.

Lakes in the enclosed drainage basin are subject

to sizable changes in their elevation, area, capac-

ity, chemistry, and biomass (Aber et al. 1997).

These changes take place mainly in response to

climatic l uctuations. During the past half century,

Devils Lake has experienced a dramatic increase

in its surface elevation on the order of 40 feet

(12 m) with corresponding increases in surface

area and volume (Fig. 8-27).

Lake elevations above 1440 feet have led

to signii cant l ooding of adjacent cities, parks,

roads, farms, sewage treatment plants, a military

base, a Native American reservation, and other

human structures. This elevation was surpassed

in 1997, and Devils Lake reached 1446 feet

elevation during the summer of 1999, at which

point the lake overl owed and began draining

eastward into Stump Lake. Despite this outlet,

lake level has continued to rise and now exceeds

1450 feet (U.S. Geological Survey 2010). Count-

less smaller lakes and marshes in this vicinity

have responded in a similar fashion, which dem-

onstrates that global warming may have unex-

pected consequences on a regional basis, in this

case leading to greatly expanded wetland habi-

tats (Fig. 8-28).

One may look also at the micro-scale impact

of climate change (see Tables 3-1 and 2), for

example, in bogs of Estonia. During warm/dry

periods, hummocks and ridges are stable or

increasing, whereas bog hollows expand during

cool/wet climatic intervals (Karofeld 1998).

Frenzel and Karofeld (2000) demonstrated at

Männikjärve Bog (see Color Plate 3-10) that

hummocks and ridges are sinks for methane; in