Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

(Box 6.1). Equally, it makes no sense at all to strive to obtain the last few tonnes of

an MSY if the money spent in doing so could be more effectively invested in another

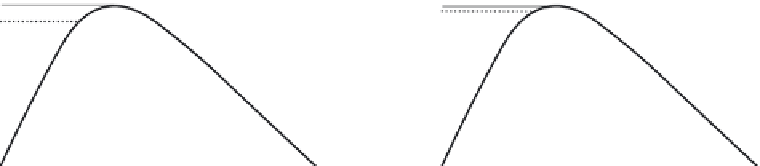

means of food production. The basic idea is illustrated in Figure 7.14a. Looked at

from an economic point of view the aim should be to maximize not total yield but

net value - the difference between the gross value of the harvest and the costs of

obtaining it. The costs have two components: fi xed costs (interest payments on ships

or factories, insurance, etc.) and variable costs that increase with harvesting effort

(fuel, crew's expenses, fi sh processing, etc.). The fi rst thing to note is that the eco-

nomically optimum yield (EOY) is less than the MSY, and for this reason alone the

chance of overfi shing is reduced. Note, however, that the difference between the

EOY and the MSY is least when most costs are fi xed (so that the 'total-cost' line has

a shallower slope; Figure 7.14b). And this is most likely to be the case in high-invest-

ment, highly technological operations such as deep-sea fi sheries. As a result, these

are more prone to overfi shing even with management aimed at optimizing economic

returns.

Spiny lobsters (

Panulirus argus

) provide the most valuable fi shery in Cuba. Fixed

costs in the fi shery are US$24,840 per boat, and variable costs consist of US$171 per

boat per day together with processing costs of US$687 per tonne of raw lobster. Most

lobsters are sold whole (value about US$12 per kg) but 30% as frozen tails (US$27.87

per kg). Some lobsters are more valuable than others, as was the case with male as

opposed to female Saiga antelope (Figure 7.7). Putting together all the economic

information for the lobster fi shery in a particular year (2002), revenues were US$55.87

million, fi xed costs were US$2.91 million, variable costs US$6.56 million, leaving a

profi t of US$46.41 million.

Previously the fi shery has been managed simply according to biomass yield and

not in terms of economic profi t. In their model, based on extensive economic and

biological data, Puga et al. (2005) determined that the long-term maximum profi t

(US$1.7306 per lobster recruited into the fi shery) would be obtained with a fi shing

effort of 24,016 boat fi shing days, slightly lower than needed to obtain the MSY

(26,405 days; US$1.7260 per recruit), but higher than what is currently the case

(18,315 days in 2000-2; US$1.6950 per recruit). On the other hand, the larger effort

(a)

(b)

Total

cost

MSY

EOY

MSY

EOY

Total

cost

Net yield

Net yield

Variable costs

Variable costs

Fixed costs

Fixed costs

Effort

Effort

Fig. 7.14

(a) In this diagram, gross yield in dollars is represented by the familiar hump-shaped curve. The economic

optimum yield (EOY), that which maximizes profi t to the fi shing industry, occurs at the point on the effort curve where the

difference between gross yield and total costs (fi xed plus variable) is greatest. At this point, the gross yield and total cost

lines have the same slope. The EOY is obtained at a smaller effort than needed to obtain the MSY (top of the curve). (b) The

effort required to obtain the EOY lies closer to the MSY when fi xed costs make up a larger proportion of total costs.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search