Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

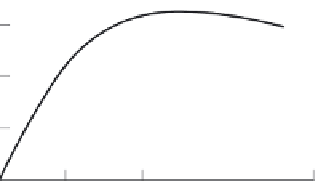

1.50

1.00

0.50

0

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

Effort (boat fishing days)

Fig. 7.15

Relationship between profi t and fi shing effort in the Cuban spiny lobster fi shery. This

curve is the top segment of Figure 7.14a - the net yield - expressed as profi t per lobster

recruited into the fi shery. The fi shing effort needed to optimize the economic yield (

F

EOY

) is

shown as a solid vertical line. The effort needed to produce the maximum sustainable yield

(MSY; dotted line) is slightly greater. The current effort (dashed line) is smaller than the

optimum, whereas the maximum effort (sometimes exerted in the fi shery) is higher than both

the optimum for economic returns and the maximum sustainable yield - such effort would lead

to overexploitation of the fi shery. (From data in Puga et al., 2005.)

occasionally seen in the fi shery (30,000 days) can be expected to produce lower

profi ts (US$1.7050) and overexploit the spawning stock (Figure 7.15).

7. 6

Adding a

sociopolitical

dimension to

ecology and

economics

'Social' factors enter the sustainable harvesting equation in two different ways:

because of the need to factor human nature into harvest management procedures

and because of political realities that sometimes work against taking ecological

advice.

7. 6 .1

Factoring in

human behavior

Management plans may fail if they simply assume people will conform with the

requirements of achieving an MSY or EOY but take no account of the way harvesters

will actually behave in changing circumstances. Harvesting involves a predator-

prey interaction: it makes no sense to base plans on the dynamics of the prey alone

while simply ignoring the dynamics of the predators - us (Begon et al., 2006). A

particularly graphic example of humans behaving as classical predators is shown in

Figure 7.16: the anticlockwise predator-prey spiral is precisely what ecologists

predict when owls feed on mice, or lions on antelopes - but this is for seal fi shermen

catching fur seals (

Callorhinus ursinus

) in the North Pacifi c in the last years of the

nineteenth century. What you see is extra vessels entering the fl eet when the stock

is abundant, but leaving it when seals are rarer. The most important point, however,

is the inevitable time lag in this response. Managers must remain wary because

whatever they might propose, a perfect, equilibrium match between stock size and

effort is never likely to be achieved. Hilborn and Walters (1992) wisely note that

'the hardest thing to do in fi sheries management is reduce fi shing pressure'. At least

the seal fi shers were eventually able to switch their effort to another stock waiting

to be exploited (halibut,

Hippoglossus stenolepis

). When alter native targets are una-

vailable, or cannot be exploited with the specialist gear in use, the temptation to

continue effort in an overexploited fi shery may be irresistible.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search