Game Development Reference

In-Depth Information

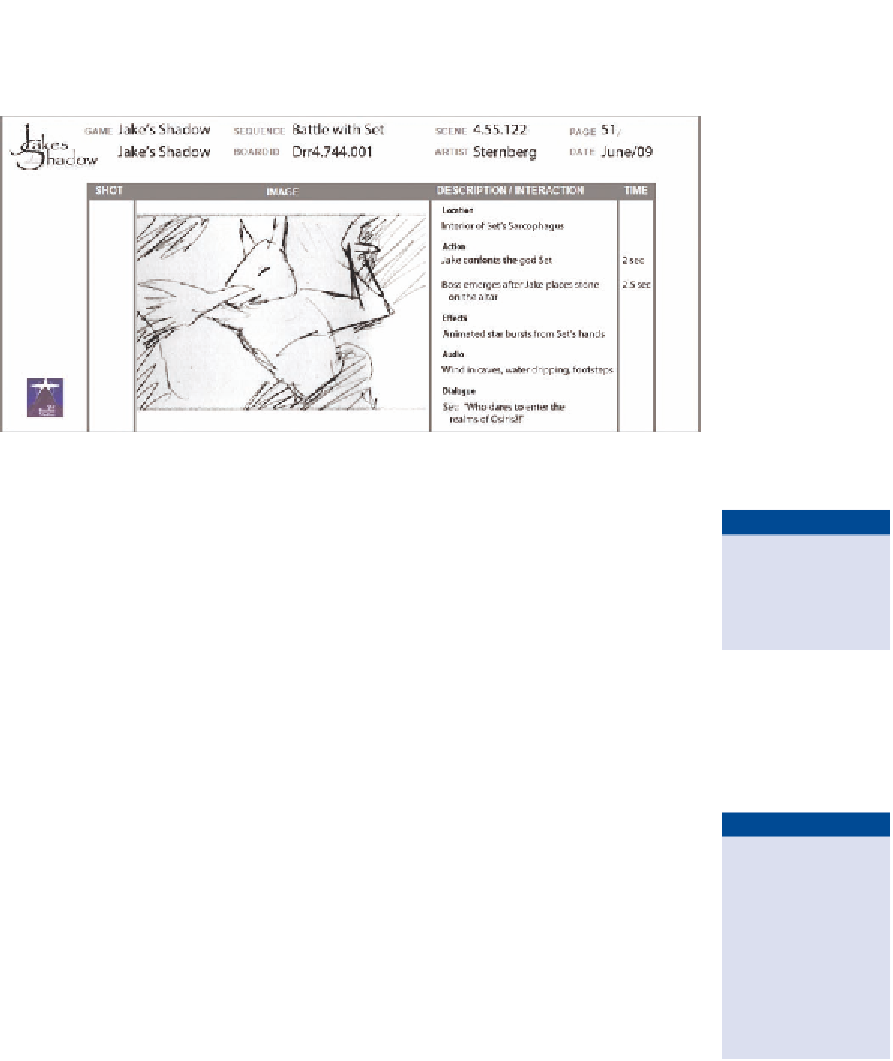

Figure 3.2 is an example of one type of template you can use for storyboards.

FiGuRe 3.2

Example of a boarded scene

This example of a boarded scene is from the game

Jake's Shadow,

which is

about a little boy who ventures into the world of the ancient Egyptian gods to

retrieve his stolen shadow. In the figure, art shows the god Set and basic infor-

mation like dialogue, location, and so on. Boards are extremely useful to help

organize story, actions, and more. They can also be scanned and cut into pieces,

after which camera moves can be added in a program like Flash or After Effects

as an animatic to provide a sense of timing for the action. That step is almost

always done with cinematics (see “Understanding Cinematics and Cutscenes,”

later in this chapter).

Creating storyboards

and flowcharts helps

others begin to see

your vision.

Flowcharts

You can create a flowchart to help map out where characters can go and how

storylines may develop and be revealed. The flowchart shown in Figure 3.3, from

the game

Pinkyblee and the Magic Chalice,

has been color-coded to show the

start point (yellow), the departure point to a next level (blue), gameplay in this

level (aqua), and a boss who can kill your character (red). Essentially, flowcharts

can be created to enhance and explain gameplay to the artists, animators, cod-

ers, and others who are building the game, especially when you have large crews

involved in a project. They don't have to be color-coded; they can be drawn in

any manner and tailored to meet the vision of the designer and whatever seems

to work best to communicate with the crew.

designers often cre-

ate flowcharts like

puzzles, keeping the

events on pieces of

paper or layers in

photoshop to move

around and edit

while honing the

design of the game.