Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

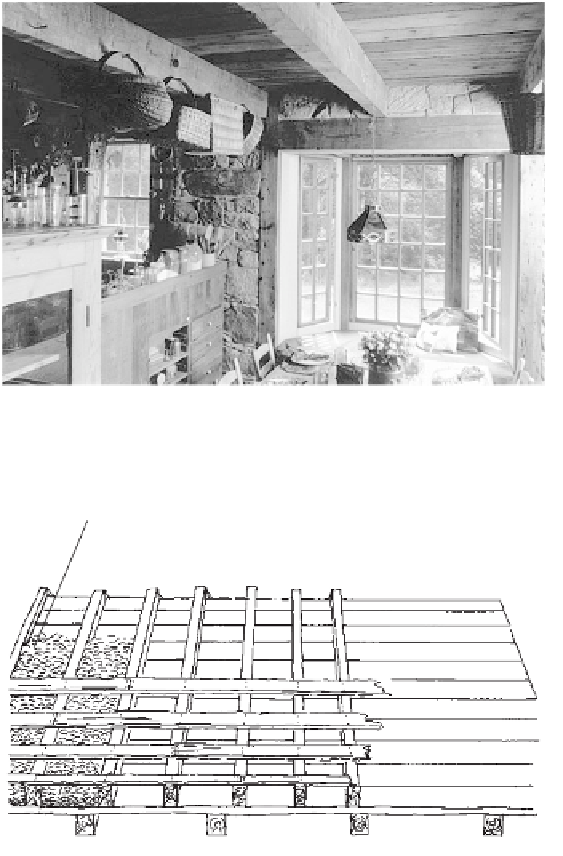

Floor joists, often of logs flattened only on top to

carry the flooring, will sometimes be warped too much

for reuse. I will usually replace these with 2≈10 saw-

milled stock when it won't show and if there's to be no

basement. If it is to be visible from below, here's where

I use newly cut beams, often cut down from recycled

old factory or warehouse timbers. Lacking these, you

can use fresh wood if it's been seasoned for at least a

year. Or you can buy kiln-dried heavy beams through

most building supply stores for a price.

The rule of thumb for joists is one inch in height for

every two feet of span. That's misleading, though,

because a 6≈10 can carry more weight than a 2≈10.

And although modern building codes require a basic

16-inch-on-center (o.c.) spacing, you may be replacing

beams set three feet apart, so they'll have to be bigger.

Also, what you're flooring them with affects the size

and spacing. In our house in Virginia, we have three-

inch grooved, splined flooring from an old cotton mill;

this spreads the load considerably, so we have fewer

but larger (6≈10) joists.

Here's where you need that conference with your

building inspector. If your log house had 2≈6 ceiling

joists on 24-inch centers, for a span of 16 feet, it may

have held a century of upstairs living, but he'll want

something more solid. Given the rule of thumb, you

should have 2≈8s that are 16 inches o.c. or heavier, but

you won't want to look up at all that zebra-stripe fram-

ing above. So suggest 4≈10s or 6≈8s, maybe 36 inches

o.c., or more, to fit into mortises in the wall logs where

the originals had been. That'll mean flooring with two-

inch-thick tongue-in-groove (t.i.g.) upstairs, but that's

a good idea anyway. You can then perhaps reuse the

old, one-inch-thick flooring from up there over a sub-

floor, downstairs where it'll be seen and appreciated.

We've gone from roofs to floors here, so let's go up

there again. You may want to keep those pit-sawn 3≈4

rafters, especially if they're mortised and pegged

nicely at the peak. You can use them as a base for your

roof, decking with boards; you may paint between the

rafters to lighten your loft. Then you can do a built-up

roof, using 2≈6s or 2≈8s on edge, toenailed on top of

the decking, with insulation between and the roof cov-

ering on top of that. It's expensive, but it looks nice.

We usually rebuild a roof using 2≈10 rafters for

more insulation and to meet the building code, deck-

These hewn 6x10 joists in our stone kitchen addition are floored

upstairs with three-inch-thick splined cotton mill flooring.

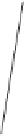

This drawing shows a double or built-up roof, which lets historic heavy

roof rafter beams show inside while fully insulating the roof itself. These

beams are strong enough to hold up the roof but too shallow to be

seen and still accommodate the thickness of insulation. This compli-

cated roof is a trade-off between the ambience of seeing these vintage

beams and spending the money and time.

ing and covering conventionally with shakes or

standing-seam metal. Then we insulate between

rafters and wall the insides with shiplapped boards or

drywall, often painting off-white to lighten the

upstairs. This gives a flat plane, not as interesting as

the old rafters but a lot cheaper. To add interest we'll

often reuse the old collar ties, or new ones made from

old material, out in the open up above head height.

These can be left with the old saw marks or planed and

oiled for the beauty of the wood grain.