Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

One of the brightest ideas extant is a duct for out-

side air to feed the flames, to be closed when there's

no fire. The air still goes up the chimney, but warm air

isn't drawn out of the room and drafts are eliminated.

I have used either a direct or a “Y” passage in concrete

beneath the firebrick in some fireplaces, with screen-

ing over the outside openings to discourage varmints.

The air comes in right in front of the fire and does its

thing nicely. A device to keep ashes out of it is a sim-

ple necessity.

Another improvement using the dual-wall box,

puts the cold-air inlets ducted under the floor to far

corners of the house. This draws cold in, leaving low-

pressure areas, which in turn are filled with the warm

airflow from the heat box outlets. If no blowers are

used, these ducts should be the full size of the inlets

themselves. With blowers, you can use smaller ducts

because the air travels faster. Without these ducts, the

circulating heat box pulls air from the room very near

the fireplace, and doesn't do much for the distant parts

of the house.

A fireplace may be flush with the inside wall, with

the structure completely outside. Or it may break into

the room and be almost flush against the outside wall.

Traditionally, it was largely outside, taking less room

space and being simpler to construct. But that meant

much of the heat was convected outside. I have built

raised-hearth, stone-to-ceiling, floor-level hearth,

heat box, and just plain fireplaces. I make some com-

promise with history here, because the old fireplaces

did such a wretched job of heating. If you plan to con-

struct a fireplace, get exact specifications; it is so easy

to foul up the joy.

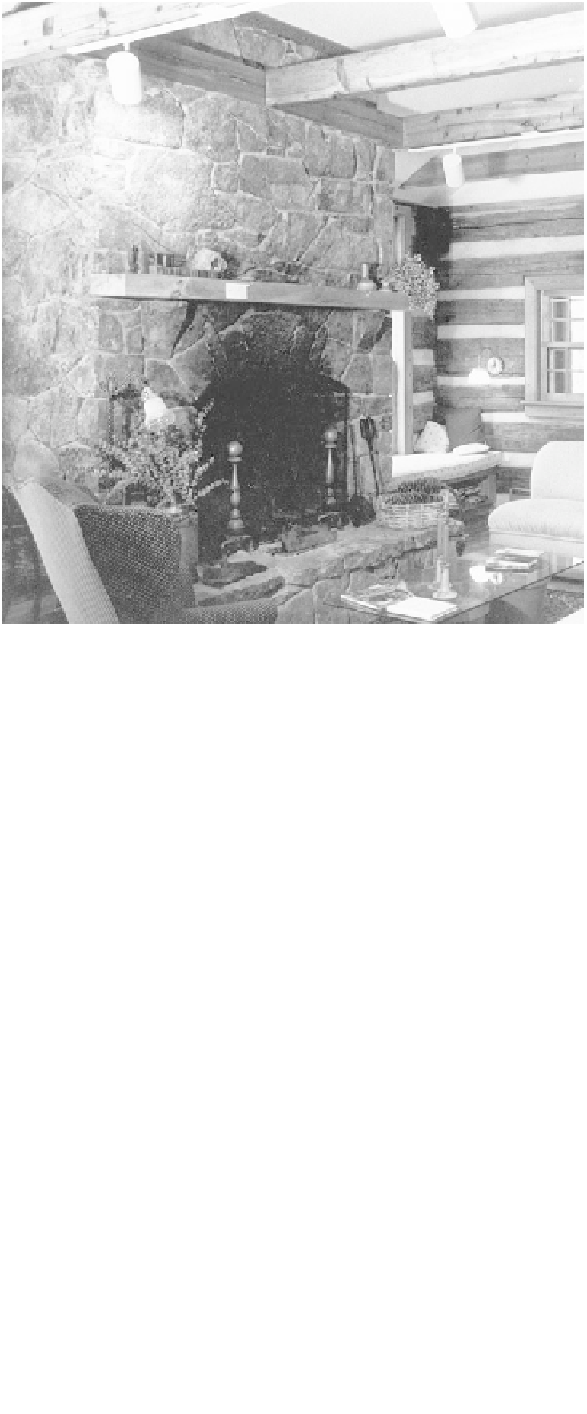

The Wintergreen fireplace is built entirely inside the house walls, which

keeps heat, convected through the masonry, inside the house. Building

codes require that chimneys be two inches from structural framing (in

this case, logs), a dilemma for all builders.

building customs of a group of settlers of similar back-

grounds became the custom of their children, and

therefore of later settlers.

The catted chimneys with their mud “cats” and neat

mini-log pens are admittedly works of art, but I will

stay with stone.

Masonry Chimneys

Catted Chimneys

In the East and red-clay South, bricks were used for

chimneys. In the mid-Atlantic and into Tennessee and

Alabama, a combination of stone and brick was com-

mon. Stone was used as a base, because the low-fire

brick often softened in the ground. Also, bricks were

easier to carry up high on the chimney.

Today, to save money, builders are using concrete

blocks and parging over them with a kind of stucco.

Stone or brick veneer over block is also common, but

in many cases is really more expensive because two

chimneys are actually being built.

I have seen, in my youth, mud-and-stick chimneys,

but haven't built an operable one. Nancy McDonough,

in her delightful book

Garden Sass,

notes the use of

mud chimneys largely in the Ouachita Mountains of

south Arkansas, and stone was almost exclusive in the

Ozarks, the Alleghenys, and the Smokies. Henry

Glassie also notes the heavy concentration of “catted”

chimneys in the Ouachitas, which, curiously, is the

home of some of the best building stone in the coun-

try. This may be simply a result of tradition — the