Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

that meant it had to go quickly. A gathering of pio-

neers could hew out a cabin and put it up in a day.

With the current revival of log building, filling the

spaces between logs is once again a major problem.

Log kit manufacturers have devised all manner of

splines, locking grooves, and plastic gaskets to substi-

tute for the old-style chinking. Some of these innova-

tions may prove to work well over the years; others

have already fallen by the wayside. Because most of

these kit logs have not stopped “moving” when assem-

bled, they have been known to twist out of the clever

spline configurations.

Either way, I've got a strong prejudice against

factory-made, fit-together log kits. They are expen-

sive, and, to me, they aren't the real thing. Building or

restoring your own traditional hewn-log house lets

you participate in history, in a sense, and it can save

you a lot of money.

Finding Out What Works

Modern materials and techniques that last but look

like traditional chinking are the key here, because they

solve the age-old problem of permanence.

I grew up around log cabins, and that meant trying

different ways to make the chinking more effective

and permanent. When I was 11, my father, older

brother, and I tore down, moved, and reassembled a

log house that had provided little real shelter because

the chinking was constantly falling out. The logs had

been notched so that they were close together, and the

voids had been filled with solid concrete mortar.

When the logs expanded during the wet season, the

chinking broke up like ice on a pond.

We shortened and renotched the logs for a wider

crack. Before we filled the space with a lime-based

mortar, we drove rows of nails across the spaces and

strung barbed wire in there. This gave the chinking

some reinforcement. And it is still intact almost 60

years later.

But still those logs shrank with dry weather, open-

ing cracks next to the chinking. Caulking seemed the

ultimate answer, but it was expensive and required

periodic maintenance. We also questioned the sense

of using stone shards and wood splits behind the

chinking mortar because they didn't seem to do much

to keep out the wind or cold. But neither did filling the

entire space with the masonry mortar.

As the years passed, I graduated from barbed wire

to chicken wire, then to hardware cloth, and finally to

metal lath, which is designed to hold plaster. I also

tried various kinds of insulation, but it wasn't much

good at keeping out drafts. Sprayed foam was better,

but messy and hard to contain as it formed. It's expen-

sive too. The best insulation that I've found is fiber-

glass batting. If it's packed more tightly than usual so

it springs outward against the logs, it really keeps the

wind out. It's not as efficient that way as insulation,

but it does work. It takes about two times the quantity

you'd use for normal insulating.

I ultimately settled on the following routine to

chink my log structures. With a chain saw, we cut a

one-inch-deep groove, a little over one inch in from

the outside face of the log. This is only on the under-

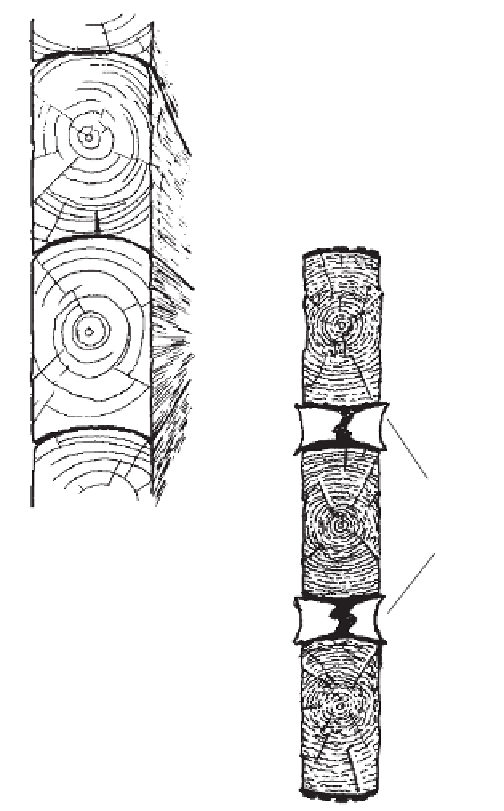

These scribed logs are fitted to go together

without chinking. Traditionally, a layer of

moss was used between them.

Often, old chinking improperly

installed acts to destroy logs

over time by catching rainwater.