Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

choose a bit. I've been able to throw out a lot of it

sometimes and still be ahead of the price game. Or get

your local saw miller to cut you some decking. If put

up green, it'll shrink, but cracks here don't matter.

Tongue-in-groove lumber is ideal, but expensive.

The two-inch-thick variety is available most places,

and will span up to six feet easily at a 45-degree pitch.

Most people who buy this think it'll be extra insula-

tion, but again, it doesn't help much.

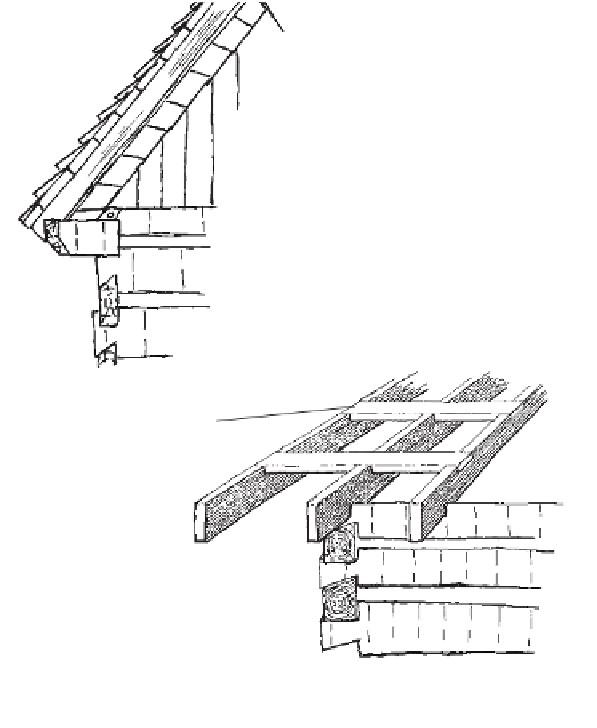

Trim the ends of the decking with an eave rafter of

the same size as the main rafters, carried on the

extended plate or lookout.

If you can, build with the top log plates extended to

support this eave rafter at the bottom. Traditionally,

this bit was avoided because older houses didn't have

much eave. When mud-and-stick (catted) chimneys

were used, the plates and ridge were extended so the

roof could shelter the chimney.

Extending the plate log to carry the

trim rafters is a good idea if you have

logs long enough. Eaves help protect

the logs but were rare in early build-

ing styles, including log cabins.

Insulation

A lookout is a cantilevered set of

braces to carry a trim rafter pair

beyond the house wall. Where

there is no extended plate for sup-

port, the lookout will do the job.

After you've decked with your chosen material, you

can staple down a layer of sheet plastic or tar paper to

seal the roof temporarily against rain while you work

inside. But take this off when you apply the permanent

roof if you insulate — which you should.

Insulation should be of a type that traps lots of tiny

air pockets, as with Styrofoam, mineral wool, or fiber-

glass. You can insulate between the rafters and finish

inside with some kind of wall if you don't want to look

at exposed rafters. Or you can put a nailing strip along

each rafter, insulate between with a layer of Styro-

foam, and cover with a recessed wall to leave part of

the beam showing. Either way, you don't want a solid

barrier, such as plastic or tar paper, outside the insu-

lation because moisture will condense. The insulation

should be at the same temperature and humidity as

the outside air.

You can nail upright beams, say 2≈6s, onto the

decking outside for a built-up or double roof. Insulate

between beams, again with something like Styrofoam,

which does an acceptable job in relatively thin appli-

cations. Next nail slats. And then nail the shakes or

metal roof to the slats. I like the Styrofoam outside

because it's waterproof. The best grade is the dense

blue stuff, which is more expensive but better insula-

tion and lasts longer. Fiber insulation that's wet is no

insulation at all. Also the foam insulates better per

inch thickness, and you don't get particles of it in your

lungs, which stay forever.

Again, the early settlers didn't insulate. If ceiling

boards, with maybe handmade rugs or bearskins over

them upstairs, held heat down in the main rooms, the

kids slept among the elements. Later, everything from

old newspapers to burlap sacks and cheap wallpaper

was applied to inner walls and roofs, but its purpose

was mainly to stop wind, and it did not impede the

flow of heat through solids.

Years ago, I used a couple of layers of Celotex, a

wood-fiber sheeting, as insulation on top of solid

decking. It was fair, but insufficient. Remember, you'll

lose most of your heat at the top, so trap it there. An

insulated ceiling will keep things warm downstairs if

you don't use the loft for anything but storage. But if

you live up there, insulate the roof, one way or another,

and let that heat go up through the ceiling. We use at

least R-19 overhead.