Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

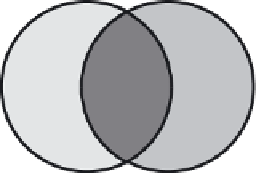

Circle A:

Adaptations possessed

by the animal

Circle B:

Challenges faced

by the animal in

its current

circumstances

2. Challenges for

which the animal

lacks corresponding

adaptations

1. Adaptations that no

longer serve an important

function

3. Challenges for which the

animal has corresponding

adaptations

Figure 8.2

Many of the welfare challenges in contemporary farming occur either because the

animal has an adaptation that no longer can find a function in modern rearing systems or because

the animal lacks adaptations to such systems (after Fraser

et

al

. 1997).

because the animal has an adaptation that can no longer find a function in modern rearing

systems or because the animal lacks adaptations to such systems (Fraser

et

al

. 1997, Figure 8.2).

Thus, the stress caused because the animal lacks adaptive strategies to handle the situation

(e.g. a noisy fan in the pig house) may be considered worse than the stress outdoor pigs experi-

ence with the fox sneaking around their paddock, since animals in the wild are primed to deal

with unpredictable conditions, of which predators are an important part. This should by no

means stop farmers from protecting their piglets from foxes (albeit by other means than by

eradicating the fox population, since the means used must comply with the ecocentric frame-

work). However, the pigs would have to live with the possibility of being exposed to this kind

of stress, which should not be the case with the noisy fan. It could, of course, be questioned

whether it would be a valuable experience for the pigs, in the sense discussed by Vaarst

et

al

.

(2000), but it would expose the animals to a wider range of experiences, and add 'excitements'

that would still be within their genetic adaptation. Thus, in Figure 8.2 the fan would represent

a 'type 2 challenge', whereas the fox would be a 'type 3 challenge'.

The ecocentric philosopher Holmes Rolston (1988) suggested handling the dilemma of

animal suffering through applying 'a homologous principle' in animal husbandry: 'Do not

cause inordinate suffering, beyond those orders of nature from which the animals were taken.

[…] Culturally imposed suffering must be comparable to ecologically functional suffering.'

The same view can be found in the organic farming movement (Lund 1996). The organic

understanding of animal welfare differs somewhat from that commonly used in conventional

farming, where the biological functioning approach is usually seen as the norm. Researchers

also prefer the latter approach, since it makes it comparatively easy to quantify welfare states.

Therefore to some extent, the criticism of animal welfare in organic farming may stem

from a different understanding of what welfare is. While organic farmers may believe their

chickens have good welfare because they have a (relatively) free life in an environment that

allows them to perform most of their natural behaviours, the conventional farmer or scientist

may focus on the risk of parasite infections, predator attacks, cannibalism and the home-

grown feed with low content of certain essential amino acids. From their point of view, the

welfare of these animals is being compromised.

Is there a general welfare problem in organic production systems?

Several issues must be considered when trying to answer the question of whether there is a

general animal welfare problem in organic production systems. The first one is the issue of