Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

1.10

1.23

1.12

1.22

1.14

1.17

.81

1.09

1.20

1.21

.75

1.04

1.10

.94

1.00

1.12

.90

1.22

1.13

.81

1.23

1.23

.90

1.00

.85

.89

.93

1.07

1.19

1.17

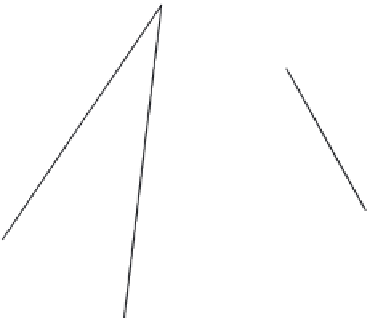

FIGURE 1.6

Allometric coefficients of traditional morphometric measurements, plotted on the organism.

Using landmarks as data does not solve all of the problems confronting traditional

methods, and one remaining problem becomes evident as soon as we try to examine the

changes in head profile over the piranha's ontogeny (

Figure 1.7

). We can see that the aver-

age slope on either side of landmark 2 must get steeper, but we cannot tell whether the

profile becomes more S-shaped, C-shaped or any other shape. This uncertainty arises

because the three landmarks provide too little information about the curve between them;

they are no better a sample of the curve's shape than the line segments connecting them.

For this reason, we need to incorporate information about points on the curve between

landmarks (

Figure 1.8

). These points (called semilandmarks) are not landmarks because

they are not individually homologous anatomical loci even though they sample points

along homologous curves. The utility of semilandmarks is even more apparent if we look

at structures whose curvature is both complex and critical to its function, like those on

the margins of rodent mandibles (

Figure 1.9

). The regions on which the muscles insert

lack landmarks but the information about the depth of the jaw, the positioning and

orientations of the muscles provided by semilandmarks is necessary for any explanation

of jaw shape. As we predicted in the Introduction to the first edition of this topic, the

limitation of geometric morphometrics to landmarks was transitory.

Geometric morphometrics may also have appeared to have a limitation not confronting

traditional methods: the restriction to two-dimensional data. But that limitation was purely

a matter of the technology for obtaining the coordinate data. The mathematical theory

poses no obstacle to the analysis of three-dimensional shapes. The obstacles lie in cost of

the equipment for obtaining three-dimensional coordinates and the details of using it,

such as the need to transport either the equipment or the specimens so that they are in the

same place at the same time. The other problem results from the difficulty of depicting

results of the analysis on a static, two-dimensional medium such as the pages of a journal.

Traditional morphometric studies did not face these obstacles because specimens could

always be measured with calipers if the equipment needed for three-dimensional