Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

4

3

5

2

6

15

7

1

14

16

8

13

12

11

10

9

(A)

(B)

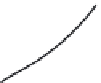

(C)

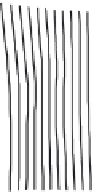

FIGURE 1.5

Ontogenetic shape change depicted in two visual styles. (A) Landmarks of all specimens; (B) vectors

of relative landmark displacement; (C) deformed grid.

Figure 1.5

, shows that the middle of the body grows faster and becomes deeper than the

rest of the animal. The limitation of this representation (and of the analysis) is exemplified

by the difficulty of interpreting the large coefficient (1.23) of the posterior segment of

dorsal head length

it is not clear whether the head is just elongating rapidly in this area

or if it is mainly deepening or if it is both elongating and deepening. We also cannot tell

if the pre- and postorbital head increase at the same rate because the measurement scheme

does not include distances from the eye to other landmarks. None of these ambiguities

arose from the geometric analysis of the landmark coordinates; the figure illustrating that

result showed the ontogenetic changes in all those specific regions. This ability to extract

and communicate information about the spatial localization of morphological variation,

including its magnitude, position and spatial extent, is among the more important benefits

of geometric morphometrics. Following the statistical analysis, which allows us to determine

which factors have an effect on shape, we can diagram the effects of the factors.