Technique

Save Time By

Understanding what cookies can and can’t do

Using Ad-Aware to knock out scumware

Setting up Internet Explorer to deal with cookies on your terms

Everybody’s worried about cookies, of course, but few understand how they work and why they even exist. I find that people have lots of misconceptions about cookies. People lose work — heck, people lose sleep — over cookies, when a little bit of plain talk and some simple prevention can reduce your chances of problems to almost zero.

I say “almost zero” because bugs have been discovered in Internet Explorer that pose a real threat to all of us. The bugs allow renegade Web sites to merrily cavort through all the cookies on your PC, even though Web sites aren’t supposed to be able to see any cookies but their own. No telling if similar bugs will crop up in the future.

This technique shows you how to fight back against unscrupulous marketing types, using a program called Ad-Aware. It also shows you why most cookies are good for you, demonstrates how you can subvert them, and offers some commonsense, quick steps to protect yourself from the “bad” cookies.

Understanding Cookies

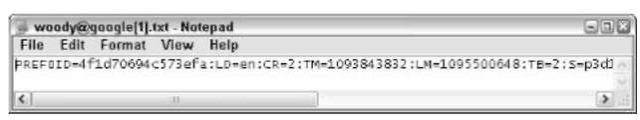

People have wasted more time fretting over cookies than any other Web topic. It’s all for naught. Most cookies aren’t evil. They aren’t even mysterious. But what are they? Cookies are simple text files that Web sites place on users’ PCs (see Figure 53-1).

• Figure 53-1: The cookie that was put on my PC by Google (www.google.com).

Web sites want to put a cookie on your machine so they can keep track of your online comings and goings. The simplest cookies contain what amounts to a customer number; when you return to the Web site, Internet Explorer delivers the cookie to the site. The Web site’s computer can look up your customer number and use that number to figure out all sorts of things. For example, on cnn.com, your customer number tells the CNN computer which regional newsgroup you prefer (U.S., Europe, Asia, and so on). On Amazon.com, your customer number tells the Amazon computer whether you have a shopping basket in the works, or any saved items; Amazon also uses your customer number to look up your buying history and pepper its pages with offerings you may find tantalizing.

Internet Explorer has several cookie settings that are difficult to understand unless you’re acquainted with how cookies work in the real world. The following sections step you through the good, the bad, and the ugly, so you can understand what IE settings make sense for you.

In most cases, Web sites stick an identifying number in your cookie. In my Google cookie, shown in Figure 53-1, that number is 4f1d70694c573efa. The number doesn’t signify anything. It’s just a handy way to keep track of what I’ve done on the Google Web site. To see what’s happening, consider this hypothetical interaction:

7. You start Internet Explorer and go to

www.google.com.

2. Google asks your computer, “Do you have a Google cookie?”

3. The computer responds, “Yes” and hands over the cookie file.

4. The Google computer looks up the identifying number, 4f1d70694c573efa, and discovers that you have an outstanding order for Froogle (Google’s shopping service) pending.

Actually, I’m the one with the Froogle order, but bear with me.

5. Google sends the computer the standard Google search page, with a little note asking if you want to check on the status of your Froogle order.

6. As you use Google, the Google computer keeps track of what you’re doing and adds that information to its database for customer 4f1d70694c573efa.

7 From time to time, for reasons of its own devising, the Google computer may send a new cookie to your computer. Your computer dutifully stores the new cookie, wiping out the old one.

That’s how cookies work. Very simple. Nothing to worry about, right? For the most part. But sometimes cookies aren’t so simple, or that quaint. The plot thickens.

Gathering information with cookies

Say you surf to www.billyjoebobsite.com, and the site puts a cookie on your PC that identifies you as

customer 4f1d70694c573efa.

Every time you interact with a Web site, Internet Explorer sends a handful of relatively innocuous information to the Web site:

Your IP address: That’s the number that uniquely identifies your computer on the Internet. If you have an always-on Internet connection, such as with a cable modem, or DSL or satellite, your IP address doesn’t change. On the other hand, if you have a dial-up Internet connection, your IP address probably changes each time you dial in.

The domain name of your Internet service provider: For example, if your ISP is Earthlink, then the domain name is earthlink.com.

Your Web browser and version number:

Internet Explorer Version 6, for example.

The Web site you just came from: Commonly called a referring URL, this information can be used in somewhat unexpected ways.

All this information can be stored in a database record for a customer number, such as 4f1d70694c573efa.

In the course of running around billyjoebobsite.com, you order Southern Cooking in a Nutshell from his online shopping center. You type in your name, address, telephone number, e-mail address, and credit card number.

Bingo.

A cookie is on your computer — one that only billyjoebobsite.com can retrieve — that identifies you as customer 4f1d70694c573efa. Now an entry in the billyjoebobsite.com computer matches 4f1d70694c573efa with a specific name, address, e-mail address, and credit card number. The entry also says you ordered Southern Cooking in a Nutshell.

In the normal course of events, the fact that billyjoe-bobsite.com has your mailing address shouldn’t cause you much lost sleep. After all, you’re the one who typed your address on its Web page. Chances are good that billyjoebobsite has a security policy that protects you (see Technique 72). No doubt you trusted billyjoebobsite to protect your credit card number when you gave it to them to process your order. The problem comes when billyjoebobsite teams up with a company that isn’t quite so scrupulous, and together they start planting spy cookies on your PC.

Passing information with spy cookies

Say that billyjoebobsite.com sells an ad to badadguys. com. That ad appears as a picture — a banner ad — on one of the billyjoebobsite.com pages. The folks at badadguys.com pay billyjoebobsite.com to run the banner ad. The ad may be so small you can’t even see it. The people at badadguys.com may be selling something — or maybe not. It’s entirely possible that badadguys.com pays to have billyjoebobsite.com run the ad, solely so that badadguys.com can harvest information about people who visit the BillyJoeBob site.

Here’s how the whole banner ad thing works:

When you surf to the page that contains the banner ad from badadguys.com, the billyjoebobsite.com computer hands over data to the badadguys.com computer, which in turn provides the ad that shows up on the page, on your computer.

Got that? That’s the way most banner ads work.

Of course, billyjoebobsite is a conscientious site that doesn’t hand out, say, your credit card number. So visiting billyjoebobsite won’t send your credit card number to badadguys. Still, as I explain later in this technique, the amount of information badadguys can gather about you and your surfing habits can be considerable.

Because the badadguys.com computer puts an ad on the page, it can stick a cookie on your machine, too — a so-called third-party cookie. It’s third-party because you didn’t go to any badadguys.com Web site: The cookie is brought along to the party when you view the ad on the billyjoebobsite.com Web page.

I tend to use the terms third-party cookie and spy cookie interchangeably. Third-party cookies, almost invariably, exist to extract information surreptitiously. They’re spies.

To see how this becomes a problem, consider what can happen if the badadguys.com cookie identifies you as, oh, visitor 123456789:

7. You surf to the billyjoebobsite.com page that has the badadguys.com ad on it.

2, The billyjoebobsite.com computer knows that you are customer 4f1d70694c573efa, so the computer looks you up in its database.

3, The billyjoebobsite.com computer contacts the badadguys.com computer and says something like, “My customer number 4f1d70694c573efa just asked for a banner ad. Here’s his name, e-mail address, and phone number. I won’t give you his credit card number, but he’s ordered a copy of Southern Cooking in a Nutshell from us, and spent $24.97. Would you send him an ad?”

4, The badadguys.com computer asks your computer if you have a badadguys.com cookie. Your computer says “Yes” and sends the cookie — the third-party (or spy) cookie — to the badadguys.com computer.

5, The badadguys.com computer looks at the cookie, discovers you are badadguys.com visitor number 123456789, and that you’re billyjoebobsite.com customer 4f1d70694c573efa.

6, The badadguys.com computer puts two and two together and updates its records for visitor 123456789 with your name, address, telephone number, e-mail address, and some information on your shopping habits — all of which are provided, as part of the advertising deal, by billyjoebob site.com.

That’s how third-party/spy cookies can be used to transmit information to a central badadguys.com computer.

Combining information with spy cookies

Soon doubleclick.com . . . er, badadguys.com has a big database. The company grows by leaps and bounds. It pays Web sites big bucks to carry their banner ads. Soon every Tom, Dick, Harry, Billy, Joe, and Bob wants to put badadguys.com ads on their Web pages.

Say one day you surf to www.tomdicknharry.com. You don’t know it, but the tomdicknharry.com Web site has a banner ad from badadguys.com, too. You sign up for the tomdicknharry.com newsletter, and buy a couple of lavender tortillas from the site.

Click-click-click. The minute you hit a page with a badadguys.com ad on it, the badadguys.com computer is updated with your e-mail address, and the fact that you bought lavender tortillas. Badadguys already knows that you’ve spent $30 to buy a Southern cooking topic. The result: You get more spam — and, no doubt, ads for lavender tortillas.

Even if you don’t buy anything or provide any more personally identifiable information, badadguys.com knows who visitor 123456789 is, and it’s relatively easy to keep full details of where you’ve gone and what you’ve done. Spy cookies make it all possible.

The spy cookie companies are fully aware of the fine line they’re treading, and most of them wouldn’t dream of asking their “host” sites to pass on credit card numbers or other financial information. But they’re still amassing enormous amounts of information, which can be correlated in unexpected ways.

With the proliferation of always-on Internet connections, collating information from spy cookies is much simpler than ever before. Your Internet address — your IP address — goes along for the ride every time you look at a Web page.

Looking for spy cookies on your PC

Are you worried about spy cookies on your PC? Don’t be overly concerned: Almost everybody has them, and if the spy cookie cow is already out of the barn, you can’t do a whole lot. How’s that for a mixed metaphor?

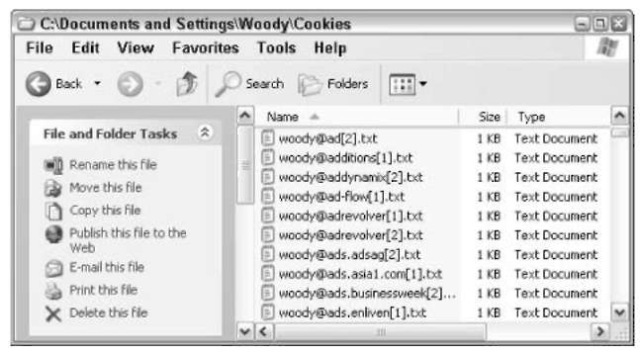

If you want to see spy cookies on your machine:

1 Choose Start My Computer, and navigate to

C:\Documents and Settings\<username>\ Cookies, where <username> is your user name.

My C:\Documents and Settings\\Cookies folder looks like Figure 53-2. It has a lot of small text files — my cookies.

2, Look for files with the word ad, ads, or advertising in the name. If you’re curious, open the ones that look suspicious.

There’s no need to delete them. In the next section, I show you how to do that automatically.

• Figure 53-2: My cookie collection.

Zapping Advertising Junk with Ad-Aware

Not all cookies are bad. But the bad ones — spy cookies in particular — can be very irritating. You can end up on spam lists. It’s highly unlikely that spy cookies will leave you prone to identity theft, but some personal information could go to a company you’ve never heard of. Your Web surfing habits could be collated. Not good.

The best, fastest, easiest way to protect yourself is with a two-prong approach. First, install a bad cookie catcher. Second, double-check your Internet Explorer settings to make sure the most irritating cookies don’t get through.

The best bad cookie blocker I’ve found is a product from Lavasoft called Ad-Aware Standard Edition. It’s free for noncommercial use. I run it every week. Amazing what it can find.

Here’s how to get it going:

7. Start Internet Explorer and go to www. lavasoft.nu.

Note the .nu.

2. In the Software category on the left, click the Ad-Aware Personal link.

That takes you to the explanation page for Ad-Aware Personal Edition. Ad-Aware Personal is free for non-commercial use. If you want to use it in a commercial, educational, or governmental setting, it costs $39.95.

3. On the right, click the Download link. Follow the instructions to download a copy of Ad-Aware Personal.

4. Double-click the downloaded file (probably called aawpersonal.exe or something similar).

The installer takes you through the steps.

Make sure you tell Ad-Aware to Update Definition File Now when you install it. Ad-Aware doesn’t automatically update its definition file unless you give your permission.

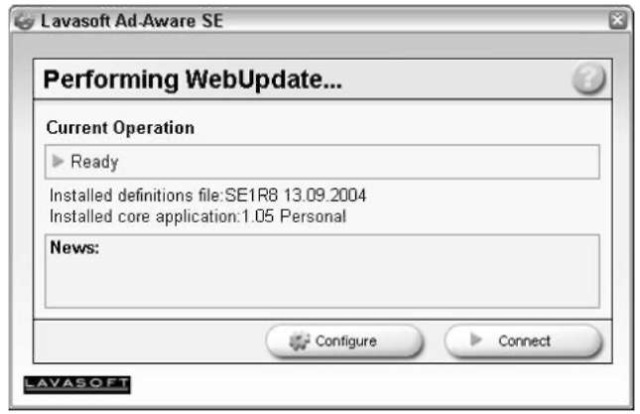

5. Ad-Aware looks for the latest definition file (see Figure 53-3). Click Connect. If a new reference file is available, click OK. Click Finish.

Wait while the reference file is updated. You return to the main screen.

• Figure 53-3: Ad-Aware looks for the latest definition file.

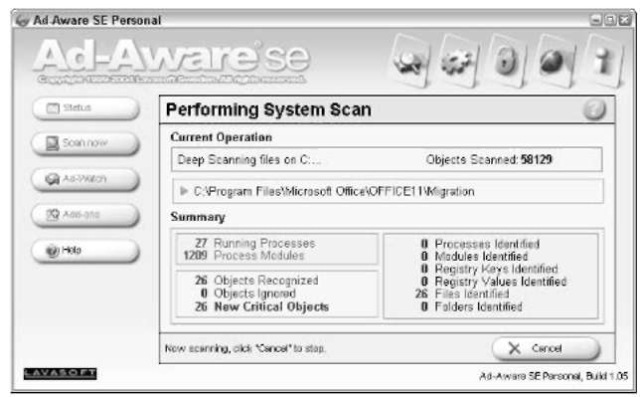

6 Click the Scan Now button.

Ad-Aware performs an in-depth scan (see Figure 53-4). Go get a cup of coffee.

• Figure 53-4: An Ad-Aware scan in progress.

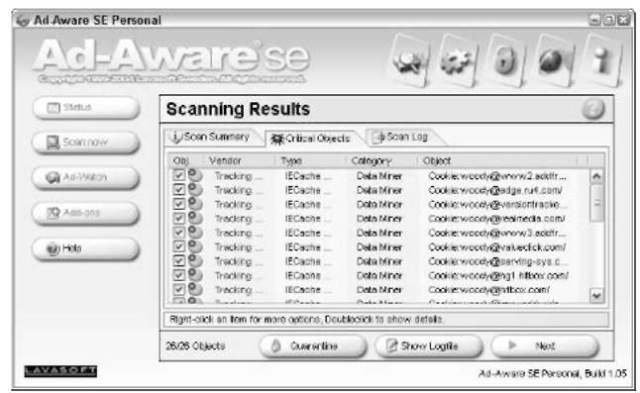

When the scan finishes, you hear a rather rude sound, and the Scanning Results dialog box shows you how many ornery critters have been uncovered.

7 Right-click the box in front of the first Object listed and choose Select All Objects.

That puts a check mark in front of each scummy object Ad-Aware has found (see Figure 53-5).

• Figure 53-5: Select all the junk that Ad-Aware finds.

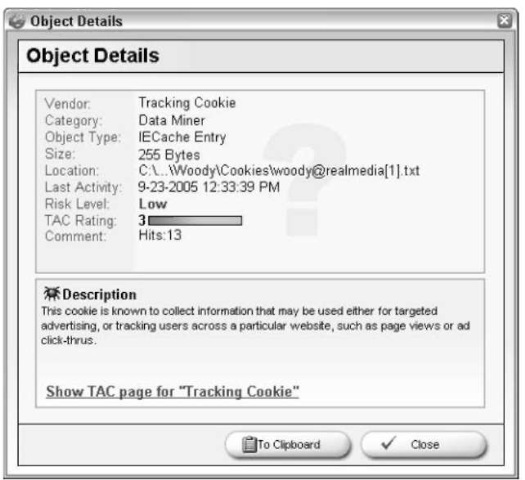

8. Scroll through the list of Critical Objects, and see if any stand out as potentially legitimate. If you think one of the entries might be something you want to keep, double-click it and read Ad-Aware’s synopsis (see Figure 53-6). Click the Close or To Clipboard button when you’re done to go back to the Scanning Results list.

In many cases, you’re given an opportunity to link to specific information on Ad-Aware’s Web site. If you have any doubt at all, check it out.

9, In the unlikely event that you see something that obviously should be saved, uncheck the box in front of it.

10. Click the Quarantine button.

Ad-Aware prompts you for a filename where it can store the Quarantined entries. It copies all the items you’ve checked into the Quarantine file, and then returns to the main screen.

• Figure 53-6: Double-click an entry to see the details.

In this case, Real Media dumped a ton of scummy cookies on my machine.

The Quarantine file can come in handy if you suddenly discover that Ad-Aware has removed something that you need in order to keep a program (or Web site) working. If an Ad-Aware scan zaps something it shouldn’t have, click Open Quarantine List on the main Ad-Aware page, and restore the offending entry.

11, Click Next.

Ad-Aware deletes all the quarantined files, and then returns to the Status page, ready to run again.

12. Click the Close (X) button to leave Ad-Aware.

In the past, I’ve advised people to avoid using Ad-Watch, the sprightly offspring of Ad-Aware that watches in the background and warns you when spy cookies are being, uh, deposited on your computer. I had a lot of stability problems with earlier versions. With Ad-Aware SE, though, Lavasoft seems to have solved the earlier difficulties. If you’re willing to spring $39.95 to upgrade to the fully licensed version of Ad-Aware (which includes Ad-Watch), you

will probably find Ad-Watch a worthy addition to your scum-fighting repertoire. Granted, most of the notices revolve around fairly innocuous spy cookies. But Ad-Watch also picks up some Internet Explorer home page hijacking attempts, and other insults to your intelligence.

Using Internet Explorer’s Built-in Cookie Catchers

Internet Explorer has a straightforward cookie catching capability, with one Achilles heel: It works on the honor system.

Understanding P3P

All major Web sites and most smaller ones have a formalized, published policy on gathering personal data and giving it away (or, more likely, selling it). Individual sites may collect individually identifiable data, such as your IP address or your name. They may limit themselves to more general data. They may hold onto the data and never share any of it. They may immediately broadcast any information you give them to the slimiest spammers on the planet. The formal privacy policy statement explains all.

Fortunately, the statements are in a standard form: The Platform for Privacy Preferences (or P3P) privacy policy relies on standardized building blocks to let a Web site tell you precisely what it intends to do with your data.

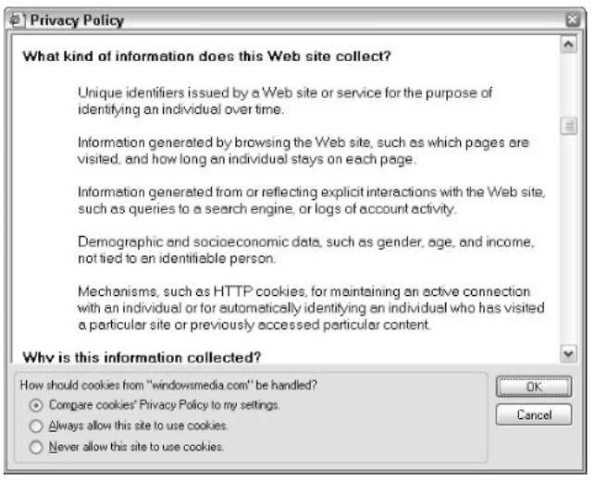

Most importantly, both humans and Internet Explorer can read a P3P policy. To see a P3P policy:

7. Start Internet Explorer.

2. Navigate to the site whose privacy policy interests you.

3. Choose View Privacy Report.

Internet Explorer shows you a list of all the Web sites that provide pieces of the current Web page. For example www.zdnet.com lists 96 separate Web sites. Windowsmedia.com lists several dozen.

4 To look at a P3P privacy report for one of the Web sites, click the site name and then click Summary.

5. If one of the policies interests you, click it.

Figure 53-7, for example, shows you the kind of information WindowsMedia.com gathers about you and sends to Microsoft’s vast database, every time you use Windows Media Player.

• Figure 53-7: WindowsMedia.com tells you that it’s collecting all sorts of information about you.

6. When you’re done, click OK and then click Close.

Internet Explorer can read and automatically interpret the P3P privacy policy for each site.

Here’s the trick. A Web site can post a P3P policy and not live up to it. There’s no computer-based enforcement. If a company fails to live up to its P3P obligations — if it sells your e-mail address, for example, when the P3P statements says it doesn’t — the organization can be taken to court. In the meantime, though, the P3P statement stands, and there’s precious little anyone can do about it.

Details about P3P are at www.w3.org/p3p.

Setting Internet Explorer’s cookie policy

Internet Explorer’s cookie settings rely on a site’s P3P policies to describe precisely what it does with your data. You tell IE how much privacy you want to maintain, and IE adjusts its cookie blocking accordingly.

To check your cookie settings

7. Start Internet Explorer.

2. Choose Tools Internet Options Privacy.

IE brings up the Internet Options dialog box.

3, Slide the bar up or down to change the cookie rejection policy. (If you don’t have a slider bar, you’re using custom settings, so click the Advanced button and modify each individual component.)

See Table 53-1 for a little help translating the settings into English. Keep in mind the discussion at the beginning of this technique: Most cookies are good; you only want to keep out the bad ones (and you have Ad-Aware to help if something gets through). I use the Medium setting, and suggest that you do, too. It seems to block almost all the bad cookies, and let through almost all the good ones.

4. When you’re done, click OK.

Your new cookie-rejection policy takes effect immediately.

If you want the full details on Internet Explorer’s cookie settings, look at www.p3ptoolbox.org/ guide/appendix.shtml. It’s heavy reading.

Table 53-1: Translating Cookie Settings Into English

| When the Privacy Tab Says This | It Means This |

| Blocks third-party cookies that do | Before IE accepts a cookie, it checks to see whether the cookie came from the Web |

| not have a compact privacy policy | page that you’re viewing, or from a Web site that contributed to the page (see the |

| discussion of spy cookies earlier in this technique). If the cookie came from a differ- | |

| ent Web site, IE goes to that Web site and checks for a P3P policy. If there is no P3P | |

| policy, the cookie isn’t saved on your computer. | |

| Blocks third-party cookies that use | Before IE accepts a cookie, it looks to see where the cookie came from. If it’s a third- |

| personally identifiable information | party (spy) cookie, IE checks the P3P policy from the cookie’s site. If that P3P policy |

| without your implicit consent | says (1) the site doesn’t collect personally identifiable information, or (2) the site col- |

| lects that information, but won’t release it unless you give your implicit permission, | |

| then IE saves the cookie on your computer. | |

| Restricts first-party cookies that use | Before IE accepts a cookie that comes from the Web site you’re looking at, it checks |

| personally identifiable information | to see if the P3P policy for that site says (1) the site doesn’t collect personally identi- |

| without implicit consent | fiable information, or (2) the site collects that information, but won’t release it unless |

| you give your implicit permission. If either of these conditions is true, then IE saves | |

| the cookie on your computer. |