Unlike many other colonies, Hong Kong was annexed by Britain not for the purposes of settlement, acquisition of natural resources, or the spreading of Western civilization, but for trade in the Far East. The first hundred years of colonial rule in Hong Kong were essentially shaped by trade imperatives.

Long before the site was established as a colony, Hong Kong Island and its adjacent peninsula were part of the larger Canton (Guangzhou) delta region in southern China, which had been a center of transnational trade between China, Southeast Asia, and the West. Hong Kong’s strategic location, its possession of a natural deep-water harbor, and its easy access from both inland China and the open sea soon caught the attention of Britain when the latter was looking for a trading base on the China coast.

When European trade with China expanded, the balance of trade became more and more unfavorable to Britain as Chinese tea and raw silk were exported to Britain in exchange for silver. In response, Britain exported opium produced in British India to China, thereby reversing the balance of trade. Alarmed by the drain of silver from the country and the increasing number of addicts in China, the Qing authorities banned the drug trade and in 1839 confiscated and destroyed opium stocks from British traders. This led to a series of armed conflicts between Britain and China in the so-called First Opium War (1839-1842). During the war, British forces took control of Hong Kong Island in 1841 and threatened to attack other Chinese cities. The Qing government yielded and signed the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, which ceded Hong Kong Island permanently to Britain. Before long, Britain and France attacked a number of ports and cities including Beijing during the Second Opium War (1856-1860), forcing the Qing court to sign the Convention of Peking in 1860, which ceded Kowloon Peninsula and nearby Stonecutters Island to Britain. In 1898 Britain gained possession of the area north of the Kowloon Peninsula on a ninety-nine-year lease from the Qing authorities, due to expire on June 30, 1997. The area was renamed the New Territories. Together with Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula, these areas became the British colony of Hong Kong. The colony remained under British control (except for a short period during World War II when Hong Kong fell into Japanese hands) until it was handed over to the People’s Republic of China in 1997.

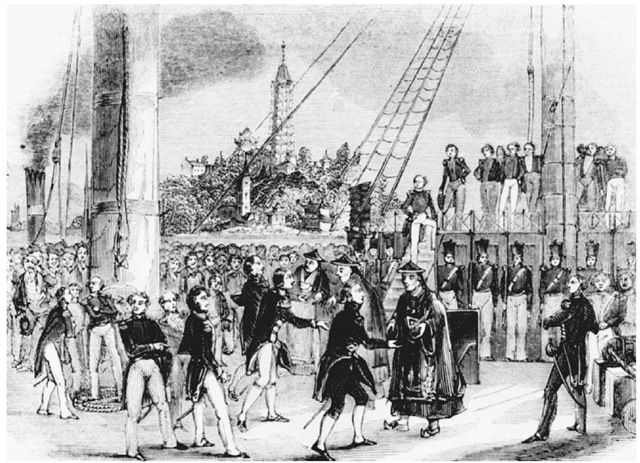

Signing of the Treaty of Nanjing. Chinese Mandarins met with British representatives onboard the HMS Cornwallis on August 29, 1842, to sign the Treaty of Nanjing, which ended the First Opium War. The scene is depicted in this 1842picture from The Illustrated London News.

Hong Kong was declared a free port as soon as the colony was officially under British possession. The intention was to turn Hong Kong into a trading post. In fact, the entire colonial administration was designed and set up to facilitate trade. Taking advantage of its strategic position and the extensive Chinese trading networks in East and Southeast Asia, Hong Kong became the regional trade center for British manufactures and traditional Chinese products such as silk, tea, and porcelain. In the early years, the colony also played a key role in the opium and coolie trade. Some Chinese merchants in the colony obtained their first tank of gold after becoming involved in the highly exploitative coolie trade under which tens of thousands of poor peasants were shipped to Southeast Asia and North America as contracted labor.

The primacy given to trade in the colony was reinforced by an imperial policy of discouraging colonial industrialization for fear of competing with British industries. When local industries sprouted in Hong Kong in the 1930s, the colonial government looked at these industries with great skepticism and refused to offer any protection or promotion. In fact, during the first hundred years of British rule, there was little attempt to invest in the colony because of a lack of confidence over the political future of Hong Kong. Economic planning and industrial investment in what the British saw as a borrowed place living on borrowed time were considered politically undesirable. The Communist takeover of China in 1949 and the Communist government’s refusal to recognize the three “unequal” treaties reinforced Britain’s belief that minimal investment in the colony was the right policy.

However, this policy did not imply that Britain simply adopted a hands-off attitude in its rule. On the contrary, the subsequent development of Hong Kong was crafted out of complex interactions between the colonial rulers, British business interests, indigenous inhabitants, and the Chinese migrants who came to the colony either to take advantage of the economic opportunity or to seek refuge from political turbulence in mainland China.

From the outset, the colony faced both cooperation and resistance from its Chinese inhabitants. On the one hand, Britain’s acquisition of Hong Kong depended not only on military strength but also on the indispensable help of Chinese contractors, compradors, and other merchants in providing essential supplies during the Opium War. After the occupation, British businesses relied on preexisting Chinese trading networks to penetrate other Asian markets. In exchange for their collaboration, British authorities rewarded the native Chinese in Hong Kong with social and economic privileges, so that these collaborators became the first generation of Chinese bourgeoisie in the colony.

On the other hand, colonial rule also met with resistance from Hong Kong’s indigenous inhabitants, especially those from the New Territories. Such resistance resulted in harsh military suppression from the colonial authorities. And as soon as order was secured, the colonial government implemented measures to pacify potential anticolonial hostilities. The landownership system in rural areas was reformed to limit the power of the pro-China landholding elite. The criminal justice system was established not only to secure law and order, but also to police the Chinese inhabitants and to secure easy convictions of suspected members of the populace.

In subsequent years, the colonial government selectively co-opted business elites (mostly British but also some prominent Chinese merchants) into policy-making bodies. It sponsored urban and rural associations to preempt anticolonial influence. It also backed one local faction against another to create social support. In addition,

Hong Kong’s colonial government manipulated ethnic and dialectal differences among the Chinese inhabitants and migrants to exercise divide and rule. In return, different social groups also made use of colonial state power to mediate relations among themselves in the creation of relationships of domination and subordination.