Abstract

This paper examines how motion sensitive remote control devices can improve the usability of television sets for older adults. It investigates the use of a pointing remote control where the actions are read and selected on the TV screen by a group of users between 65-85 years old. It was seen that the test participants universally wanted a more usable and less complicated device in both appearance and employability. The preferences in relation to channel choice were relatively narrow, mainly in the use of only 4-7 channels. The argument is proposed that the use of differing design principles facilitates older adults in also becoming proficient users of new technologies, especially focusing on the use of digital television (DTV) and the many opportunities and options to access new features that arise.

Keywords: interaction design, universal design, pointing, motion sensing, accelerometer, Wii, remote control, older adults, aging, attractiveness.

Introduction

The need for an alternative to the traditional TV remote control comes from the frequent problems older adults have in choosing which buttons to use for activating a certain feature, trouble seeing and pressing the desired button without having to switch to reading glasses and interpretation of the labels on the buttons. The solution considered here is using gestural interaction, where a gestural interface is programmed to interpret human articulation, via a pointing remote control.

The empirical data in this paper is based on interviews that were conducted with older adults from 65 to 85 years of age. It addresses some of the initiatives in relation to the target group that already exist and looks at whether any of these have had success. Moreover it introduces an alternative user interface than that which is based on using a pointing remote control.

Older Adults and the Television Remote Control

During the past few decades, there has been a rapid evolution in the area of information technology, including television. New technology has been introduced for playing recorded television and commercial films, such as HDD-, DVD- and blu-ray recorders. With the advent of set-top boxes (STB) and DTV there has been the introduction of many new services such as cable and satellite television service, pay-per-view films and video-on-demand [1].

All these available options present challenges as well as opportunities. For example, while typical end users prefer having more options to choose from rather than fewer, this is counterbalanced by a desire for the selection process to be both fast and simple. When older adults are considered, the majority want fewer options and a simpler way to manage the control and it does not have to be particularly fast [2]. Unfortunately, though, the selection processes for many systems and media interfaces are neither fast nor simple. Since Adler introduced the world of remote control in the early 50s [3], there have been major advances in the interface design and many new technologies such as touch sensitive displays and accelerometers, but the advanced models are often too expensive for the average user. A small LCD display and an increased number of function buttons have often been the only major developments on remote controls in the broad consumer market.

Newell claims that we need to devote more research efforts to designing artefacts to control our technological homes to support older adults people [4]. An increasingly ageing population is a very pressing challenge to accessible computing [5], with the over-65 age group expected to increase sharply. By the year 2040 the over-65 age group will increase by 70% above its present level in Denmark [6]. This is not a local trend; also Europe is experiencing a major demographic shift. By 2025 the proportion of the population over 65 is expected to increase from 20% to 28% [7, 8].

At the same time, the lack of accessibility to many ICT-based products and services is a major barrier for many people. Currently 30% of Europe’s population is not actively participating in the information society [9]. It is also worth noting that the expected number of people with cognitive impairment is expected to grow faster than the number of older adults people and they diverge dramatically after 2036 (see fig 1).

Fig. 1. Projected changes in numbers of people aged 65 and over and in those with cognitive impairment in Britain by year (1996-2061) [9]

When looking at the demand in conjunction with TV sets, a study made by the UK National Institute of Adult Continuing Education (NIACE) found a correlation between age and leisure-time activities [10]. 21% of 17-19 years olds spend more than 11 hours a week surfing the Web compared with just 2% of those aged 75+. However, 40% of 17-19 year olds and 80% of those aged 75+ spend more than 11 hours a week watching TV. Radio listening was also common among the older adults.

Table 1. %age of respondents by age group participating in the specified leisure time activities for 11 hours or more

|

Age |

17-19 |

20-24 |

25-34 |

35-44 |

45-54 |

55-64 |

65-74 |

75+ |

|

Surfing the WWW (%) |

21 |

19 |

12 |

12 |

6 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

|

Watching TV (%) |

40 |

43 |

49 |

52 |

62 |

71 |

80 |

80 |

|

Listening to the radio (%) |

12 |

18 |

22 |

23 |

25 |

31 |

34 |

30 |

|

Number of respondents |

221 |

416 |

803 |

954 |

761 |

808 |

545 |

423 |

New Digital Opportunities Impose New Demands on Interaction Design

There are many new services possibilities arising from the introduction of DTV. The services that today often come with providers of set-top boxes are all directed at improving one’s programme schedule for the individual channels and provide access to more content. Services include:

• EPG (Electronic Program Guide).

• VoD (Video on Demand).

• Watch an ongoing broadcast from start.

• Scheduling upcoming broadcasts from EPG.

• Access the library of past displayed works by the Public Service channels.

This is only the beginning of the DTV era. Many new services will emerge and a many of these will bring focus on the social aspect of having the viewers interconnect and support socially oriented activities and a social network through DTV services [11]. This can provide an opportunity to bring lonely older adults out of solitude and is an important factor as to why it is so important for older people to be able to adopt DTV [12]. This then presupposes the need for appropriately designed services that accommodate the older adults’ life situations, their age-related conditions and, ultimately, include the best possible interaction device to control them.

Attractive Inclusive Design of Remote Controls

Looking at the many variants of remote controls that are on the market today, there is a discrepancy between the way buttons, displays, packaging, etc. are designed and the need and the performance of the older consumer. To provide access to the potentially sizeable market share of the older adults, it is necessary to give the older adults people positive reasons to select a new product. If products and services can be designed that they feel comfortable with whilst also supporting their skills and independence, then that goal will be reached. Thoughtful, inclusive design, in most cases, creates products, services, environments that work better for people of all ages and abilities and hence produce wider appeal and revenue.

Therefore it is obvious, that a proper implementation of a motion sensitive remote control needs to follow the 7 principles of universal design. There is one further consideration that is often neglected, namely attractiveness. It is somehow embodied under the principle of Equitable Use, which deals with avoiding segregating or stigmatizing of users and makes the design appealing to people with diverse abilities.

Attractiveness covers also aesthetic value, which is also vital for the success of an inclusive product. When designers are told to design for old and disabled people, it appears that they have a tendency to design for stereotypes and emphasize on function rather than style. It cannot be a surprise that older adults people with functional disabilities and disabled people, just as everyone else, wish for products that offer function, dignity, and enjoyment and express their desired personality. In other words, there is a divergence between the designers and the users.

Existing Remote Control Solutions for Older Adults

Working with older people as the target group sharply identifies the restrictions that are present within this age segment. Even though most older adults are healthy, there are known variations of age-related conditions. Many people in this segment have decreases in functional capabilities, arising from changes to vision, cognition and dexterity, as well as cultural and generational differences with technology [13, 14].

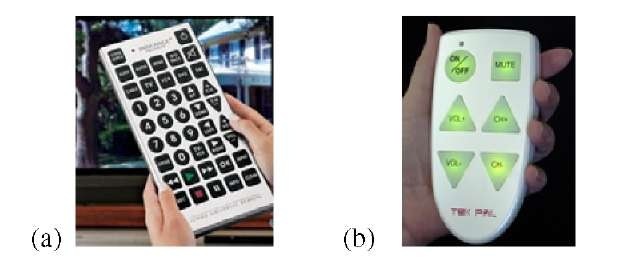

This emphasises the need to take special considerations when working with design of digital applications and services to support the needs of the older adults. The best known efforts to meet the older adults generations’ difficulties have primarily been focusing on making much larger buttons and thus the physical size of the device have increased (see fig. 2a and 2b). Two of the most obvious flaws are the placement of buttons and the printed text on the buttons that can cause confusion and also the physical handling of the large remotes can be problematic. The Innovage Jumbo Universal Remote Control (fig. 2a) also needs to be programmed to the individual TV set, and, according to sources on the Internet [15], this device comes with very limited directions on how to program the device. Others such as the TekPal (fig. 2b), meet the desire for a more handy device and stick to the absolute basic functionality, but omit many useful functions, e.g. switching input (DVD, VHS, etc.) and Teletext., which is used by half of those aged 65 and over [10].

Fig. 2. (a) Innovage Jumbo Universal Remote Control and 2(b) TekPal

Looking away from the physical artefact, the configuration menus and the graphical interface on the screen are often very confusing for the older adults person. It has already been demonstrated that the older adults represent a large proportion of the TV viewing public. Simultaneously they belong to the segment of the population that is least familiar with the conventions used when presenting information digitally.

A growing number of the older population are becoming familiar with computers, but for many it can present a challenge, when interpreting icons, links, hierarchies and menus, – all items that are widely used in the television interface today. There is a solid opportunity to affect a change by studying new alternative approaches to the use of remote controls amongst the older adults.

Interaction Experiments with Pointing Remote Control

The design process for this paper used Design Research Methodology (DRM) of Blessing and Chakrabarti as the methodical research strategy [16]. Using this method a correlation of the empirical data, the theoretical development and the practical work was gained.

Stage 1 - defining the problem: a picture of the target group for the research was provided using literature combined with surveys and 6 semi-structured interviews.

Stage 2 - developing a solution: the conceptual design process and development of a solution to be used for the final user test.

Stage 3 - evaluating the solution: performing the final user tests. During this stage paper prototyping and extended use of the Think-aloud method, although Dickinson claims that the method can be problematic with older adults, especially if conducted under laboratory conditions. [17]. Consequently, the sessions in stage 3 were held in the test participants’ own private homes.

Stage 1 – Defining the Problem

The results of the interviews with 6 older adults led to a clearer understanding of the target group and provided valuable input that was used in the design process. Furthermore it revealed the severity of the participants’ disabilities. Table 2 shows the categories that describe the respondents’ TV habits.

Table 2. The 6 interview respondents’ TV viewing habits

|

Results from |

Age |

Gender |

Television |

Watching tv |

Using |

Sum of |

|

6 participants |

|

M/F % |

usage |

|

TeletextTV |

watched |

|

|

|

|

h/week |

|

|

channels |

|

Average |

74 |

50/50 |

32.8 |

5.8 |

seldom |

5 |

|

hours/week |

days/week |

A disability survey was presented to the respondents to classify their age-inducted disabilities. The answers from the six respondents were quantified after Keates and Clarkson’s disability scoring table [18], as shown in Table 3.

The average time of watching TV per week was 32.8 hours, with a span from 8 to 80 hours. This was about 10% over the public average according to a Danish survey [19] and expected for the age segment according to the NIACE survey [10] and Stein Institute for Research on Aging [20]. The participants watched TV on average 6 out of 7 days.

Table 3. The disability severity levels for the 6 interview respondents – lower numbers are more severe impairments

|

Value |

A(F77) |

B (M72) |

C(F75) |

D (M66) |

E (M81) |

F (F69 ) |

|

Locomotion |

L4 |

- |

L2 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Reach & Stretch |

RS8 |

- |

RS3 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Dexterity |

D11 |

- |

D5 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Vision |

S8 |

S9 |

S7 |

S9 |

S9 |

S8 |

|

Hearing |

H8 |

- |

- |

- |

H6 |

- |

|

Communication |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Intellectual |

I7 |

- |

- |

- |

I1 + I7 |

- |

Teletext was not as commonly used among the respondents as expected, with only seldom use. Many of the participants said that they were very selective when it came to selecting which channels they watched and were especially keen to avoid the reality TV shows on the commercial TV stations. The mean number of channels that they liked to follow was 5 (range: 4 to 7).

Stage 2 – Developing a Solution

In order to find the choice of preference for the test, an evaluation was made on some of the larger participants on the market of motion sensing remotes. These devices included the Nintendo Wii Remote (WiiMote), Hillcrest Freespace Technology (Hill-crest Loop, Kodak Theatre HD Player and the LG Magic Motion Remote) and Philips uWand. Based on device availability and expressed user preferences, the Hillcrest Labs Loop (fig. 3) was selected for further research.

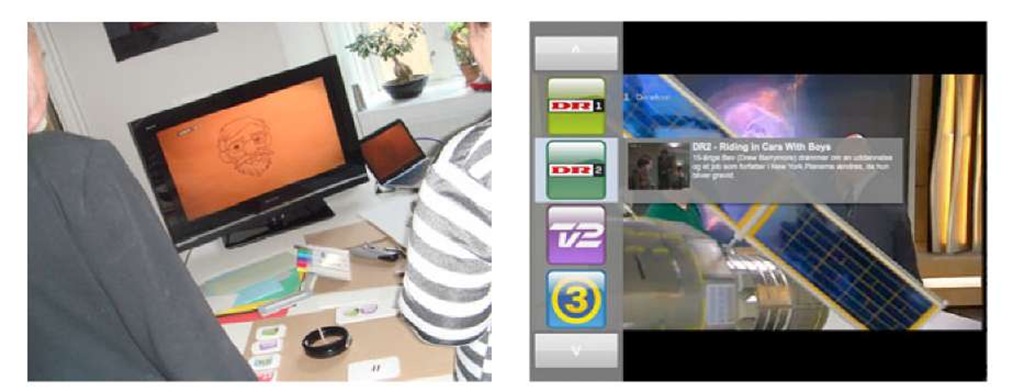

Fig. 3. A participant holding the Hillcrest Loop remote

Exploratory test sessions were held as a combination of a Think-aloud test, where existing solutions were evaluated, combined with a creative workgroup exercise, where the objective was to perform a conceptual modelling of a pointing TV interface. Flex framework for Flash was then used to create a prototype for a TV interface that could be controlled by moving a pointing device around with a single button to confirm actions. The prototype has four active areas, which can be activated by hovering the pointing device on one of the sides.

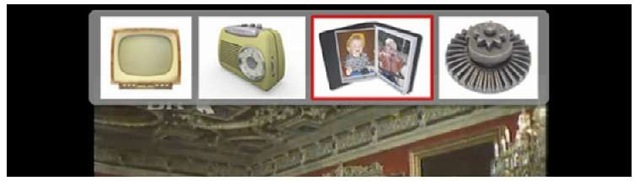

A TV Channel selection bar with program description on the left side (fig. 4), Volume and mute on the right side, the top bar showing available options (TV, radio, photo album, settings) fig. 5, and a Pause / Play button at the bottom.

Fig. 4. From paper prototype to Flash prototype

Fig. 5. Option bar on top

The reason for building the prototype in Flex was simply because it allowed for clean separation of layout and code not unlike HTML/JavaScript. MXML is a markup language based on XML which in Flex offers a way to build and layout a graphical user interface using many standard user interface elements. For the interactivity, Ac-tionscript was used, just like in Flash. Flash Builder (previously named Flex Builder) was the tool used to build Flex based apps. Besides programming in a text environment, it also contains a graphical editor to quickly layout an application and quickly allows assembling a working prototype.

The challenges with pointing remote controls

If a person is skilled with a particular remote control, there is no doubt that traditional tasks can be done a lot faster than using a point and click paradigm. However, speed was not the goal here, instead it was to enhance television usage.

Gesture based remotes are evolving rapidly. The Philips uWand has contributed with many new developments in this area, giving the user the ability to drag a picture from the television screen to a digital photo frame and easily zooming in by just dragging the remote towards away from the screen. The possibilities are great and, if the principles from inclusive design are adopted, then there is a great opportunity with this technology to create solutions for all.

Motion-sensing remotes all need some kind of receiver, and until there is more evidence of next-generation television sets with built-in receivers like the LG sets, the external sensor bars or RF-receivers need to be connected to a computer / set-top box. Introducing pointing technology to an older adult, where the only functionality they require is channel and volume control, requires an external computer with TV tuner. This can be a major obstacle for the implementation.

Stage 3 – Evaluating the Solution

User trials with the prototype were conducted with 6 respondents.

Feedback: test remote (Hillcrest Loop). There were confused minds about the form factor of the Loop remote. There were several who stated that the design was too modern compared to their taste. Many of the respondents then later realised that the alternative shape was practical to hold on to and felt more natural in their hands compared with conventional remotes. Regarding the weight, the respondents were divided in three categories; but the majority found it to be satisfactory. A small experiment that was conducted with three different prototypes of remotes also identified the importance of making remotes for older adults lightweight to allow for arthritic hands. Habituation to the round shape was difficult for the older adults, since it was not easy for them to adjust to new shapes for familiar artefacts.

Working with cursors caused a bit trouble for a few of the participants since it was an entirely new experience for them. Half of the respondents were frustrated by the sometimes sloppy pointer recognition, which required occasional reorientation.

Feedback: screen interface. The respondents were surprisingly fast in understanding the pictograms displayed on screen. They quickly adapted to the hidden four active areas and knew which area they had to activate by hovering the pointing device over the side. One of pictograms, the mute button, did give rise to some misunderstanding. Most of the participants had trouble finding the mute button on their own traditional remote, and several did not know if they had one. A smaller proportion of respondents did not understand the mute button’s function. Two users chose to switch off the whole TV set to mute the sound.

One participant was not quite sure where she had a specific channel (DR2) placed, and she was generally positive to the clearer interface in the flash prototype, where she could see 4 channels simultaneously.

Feedback in general. After the respondents had been allowed to get accustomed to the new system, they had an overall positive attitude towards a pointing remote control solution. Two respondents were so comfortable with the situation and got so used to manage the remote control that they began to explore the upper feature menu and the hidden extra four channels that appeared when they pressed the down arrow.

Redesign Recommendations

The circular form of the Hillcrest Loop presented problems for many of the test participants when lifting it from a flat surface, such as a coffee table, with the users often picking it up upside down. This problem could be eliminated with a coloured marking on the black ring indicating ideal hand placement and direction. An arrow was temporarily attached to the Loop that alleviated this problem, but this cannot be considered an adequate permanent solution.

Finally, the loop form needs to possibly be discarded and a return to a straight and narrow form is re-adopted, as exemplified with the LG Magic Motion Wand. In this instance it needs to be appreciated that such a device is often used in only a semi-lit environment and so a certain texture need be applied to the controlling surface so the user’s hand can feel its way to the user position.

As for the interface, the text size should be enlarged for the program information pane in the next version and improved icons should be developed for the mute and settings functions.

Conclusion

First and for all, it is essential to realize, that it is close to impossible to provide a design which fall into everyone’s taste. Even though the concept of inclusive design for "everyone" here means the older adult test participants, there are so many differences when it comes to describing their physical, sensory, motor and cognitive abilities. It is simply not possible to include these broad amounts of differences in one design process. Nevertheless it was pleasing to acknowledge the acceptance of the novel remote, although it would have been much more likely to receive an even more positive feedback, if a motion sensing remote as the LG Magic Remote was used, since it shares the form factor with the remote they are familiar with and contain the possibility to adjust volume on the remote.

There is a strong indication that the older adults have the distinct opportunity to employ motion sensitive remote control devices. The only concession, as with any TV user, is that any particular TV interface must be customised to individually suit their needs. Also it has been seen that older adults persons are able to adapt to a novel remote, which was confirmed when five out of the six respondents showed interest in the new TV interface presented in this paper.

![Projected changes in numbers of people aged 65 and over and in those with cognitive impairment in Britain by year (1996-2061) [9] Projected changes in numbers of people aged 65 and over and in those with cognitive impairment in Britain by year (1996-2061) [9]](http://what-when-how.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/tmpC92_thumb.jpg)