Abstract

Online Personal Health Records (PHR) software has the potential to provide older adults with tools to better manage several aspects of their health, including their use of medications. In spite of this potential, we still know little about how to make PHRs accessible for older adults. We also know little about how to design PHRs in a way that will enable older adults to get a valuable return on their time investment in using such systems. In this paper, we present our experience partnering with a group of older adults to obtain design guidelines for the design of a PHR with a focus on medication management. We discuss the outcomes of our design partnership and provide an overview of the design of a web-based PHR we designed based on these outcomes.

Keywords: Older adults, personal health records, medication management, design guidelines, privacy, personalization.

Introduction

Access to accurate and up-to-date health records, including medication records, is crucial for doctors to provide adequate care for older adults. When older adults use the services of multiple health providers, the potential for doctors making decisions with inaccurate information increases. This is compounded by cognitive declines many older adults face, which can hamper their ability to recall information on medications, conditions and so forth.

Online Personal Health Records (PHRs) have the potential of alleviating this problem by providing older adults with a repository of health information that is easy to edit and share. However, little information is available on how to design them taking into account the needs and abilities of older adults.

In this paper, we present our experience partnering with a group of older adults to obtain design guidelines for the design of a PHR with a focus on medication management. We discuss the outcomes of our design partnership and provide an overview of the design of a web-based PHR we designed based on these outcomes.

Related Work

Challenges in Designing for Older Adults

As adults get older, declines in cognitive, perceptual and motor abilities affect their use of computer technologies. Some relevant examples of declines in cognitive abilities include those in fluid intelligence [3] [29], working memory [3] [19] [28] [30], learning [28][1][23], and the ability to filter irrelevant information [29][35]. These declines have led, for example, to recommendations of longer training times for older adults [16] [24] [33] and minimizing visual clutter in user interfaces, including the number of options available at a given time [36][17][37].

Declines in perceptual abilities often result in older adults having vision problems [13][27], as well as hearing problems [4][26]. These declines can affect interactions with computer technology as most software communicates with users through a visual display often accompanied by the use of sound. Using larger fonts and a higher contrast between text and background can help remediate some of these problems [37][2][9][12]. Multimodal feedback (e.g. using visual, audio and tactile means) has also been recommended [10][32].

Age-related neuromuscular changes combined with cognitive and perceptual challenges affect the performance of older adults in pointing tasks [7][34][21]. Not surprisingly, results from a number of studies have found that older adults have difficulty using computer pointing devices such as a mouse, with various strategies proposed to address this problem [8][14][15][31].

The lack of experience many older adults have in using computer technology poses additional challenges, for example, in being confident in their use of computers [11][20][6].

The challenges outlined in the previous paragraphs suggest that older adults require user interfaces designed specifically for their background, needs and abilities. User interfaces designed for young adults who are heavy computer users are unlikely to provide older adults with effective, efficient and satisfying interactions. Software for older adults should be designed using user-centered design techniques, directly involving older adults in every step of the process.

Online Personal Health Records

Dozens of online PHRs are listed in the myphr.com website, with some major players joining the list recently, including Google Health and Microsoft HealthVault. In spite of the availability of all these systems, little research has been conducted on PHRs designed specifically for older adults [25].

Research Goals

Our primary objective was to obtain requirements and specifications for the design of a PHR targeted at older adults with an emphasis on managing medications.

Description of Activities

We held twelve one-hour sessions over four weeks in July and August of 2009 with a group of eight older adults at the adult retirement community where they resided. Four of our participants were male, four female. Their median age was 78 (min=71, max=82). All participants reported taking at least one medication daily, using the web for at least 30 minutes on a typical week, and having an email account.

In each session, we introduced a question and then broke up into small teams of two to three older adults and one researcher. The small group activities involved older adults providing feedback on low and high-fidelity prototypes by writing on sticky notes things they liked, did not like or would like to change. We conducted similar "sticky note" activities to gather information on specific questions. After gathering sticky notes from small groups, we put together affinity diagrams on a whiteboard, and discussed the outcomes with the entire group.

In addition, we later held three one-hour sessions of a similar format with a different set of eight older adults to validate our system as we designed it. This group was also gender balanced, had a median age of 75 (min=65, max=81), and reported taking at least one medication daily, using the web for at least 30 minutes on a typical week, and having an email account

Principal Findings

Older Adults Want to Keep Track of a Lot of Information but Are Willing to Enter Very Little

Participants listed over 20 separate items they wanted to track for each medication. These included:

• name and contact information for doctors and pharmacists,

• the purpose of the medication,

• how to take it (including restrictions),

• all dates associated with the prescription (e.g., date filled, expiration date, when to refill),

• strength or dosage, medication form (e.g., tablet),

• how long to take the medication,

• the name of the manufacturer,

• information on side effects and interactions,

• the condition for which the medication is being taken,

• what to do if a dose is missed or too much is taken,

• an image of what the pill looks like, and

• side effects observed by patient

At the same time, the participants saw having to enter all that information as a major barrier in using a PHR. This was clear in a session in which participants saw three prototypes to enter the data they had identified. Their feedback was that they would be highly unlikely to enter all that information.

During a separate session, we showed participants an online system that could enable them to print out a list of their medications with a minimal amount of information about each. The lesson learned during this session was that participants were willing to enter limited amounts of information (e.g., six items per medication), and that PHR designers should identify the most important items to keep track of and ask users to enter only these.

For medications, the top items participants wanted to track were: name, dose, how to take it, why it was prescribed, and information on precautions and interactions.

Medication Warnings Written for Health Care Providers Are Not Appropriate for Older Adults

In order to learn about how to deliver medication warnings to older adults, we began by showing adults warnings written for health care providers. The first session we discussed warnings, we obtained feedback from participants on two unmodified ACOVE [18] warnings. While participants found the warnings generally understandable, they had issues with some of the vocabulary (e.g., what is a "vulnerable elder").

In addition, they were concerned by some of the implications of a warning that said that older adults should not take a particular medication (propoxyphene). Our participants wondered why doctors would prescribe such a medication in the first place, and why a pharmacist would not have caught the problem. This discussion occurred prior to recent withdrawal of this drug from the US market.

In this session and others, participants were concerned about the validity of the warnings, as they could be perceived as a way of promoting a competing product. It was difficult for some participants to understand how warnings would be generated, a problem that was related to an overall lack of understanding of how the Internet works. In spite of these concerns, there was strong belief that patients should receive these warnings.

Suggestions for changes included using shorter sentences and less technical vocabulary (e.g., using "pain relief medication" instead of "analgesic"). In subsequent sessions, we obtained iterative feedback from high-fidelity prototypes to study how warnings should be delivered to older adults. We learned that it helped to provide three levels of information. The first level, always visible, consists of a short phrase that provides a good idea of what the warning is about. Participants agreed strongly that this first level should clearly explain what the safety concern is. Clicking on this first level warning, pops up a window with a one to two paragraph warning, which can in turn be expanded into a scrollable, detailed, third-level warning.

Perceived Privacy and Security Are Crucial for Adoption

We heard a lot of concerns about the privacy of the data, which were exacerbated by a lack of understanding of how the Internet works. Many participants had difficulty understanding where and how data would be stored and how it would be secured. There were many mentions of "big brother" looking over their data and of employers or pharmaceutical companies taking advantage of the data, in detriment of patients.

Some of the participants appeared to remain suspicious of our true motivations through all three weeks of interactions with them. This provides a sense of the great challenge in getting older adults to trust PHRs, and in particular, the way they handle privacy and security. The lesson we learned is that no matter how good the privacy and security features of a system are, perceived privacy and security are just as important. Older adults will not use a PHR if they do not perceive that it will keep their data secure and private.

Participants also had concerns about where content provided by the system would come from. This was the case for medication warnings, as mentioned in the previous section, but also for any other advice provided through the system.

Affiliating the PHR with a trusted institution and/or making use of appropriate metaphors may help in both regards. For example, our participants appeared to trust Medicare and insurance companies with handling their health information. Likewise, metaphors could be used to present the PHR as an extension to their memory or as a virtual version of the information they would like to keep in their purse or wallet.

Adapt to the Needs of Specific Patients

Presenting a PHR that is customized to individual needs would make it more likely for our participants to adopt it. For example, a PHR for someone with diabetes would put a greater emphasis on tracking blood sugar and diet. This was apparent from discussions in several sessions, where participants would suggest features that were tailored to their specific needs, but would not be relevant to others who do not share similar health concerns. It was also clear that participants would be unlikely to customize the user interface if given the chance, and that this could lead to further confusion. Instead, participants said they would be most comfortable if they could access pre-designed user interfaces for the most common ailments.

Discussion

Participatory Sessions at a Retirement Community

We found great value in engaging older adults over three weeks in discussions on how to design better PHRs for older adults. The depth of the discussions and the depth of the recommendations and guidelines that we arrived at would not have been possible with shorter engagements. In particular, with a population that in many cases is not technically savvy, we learned that meeting over several days helped them understand our goals better, and helped us understand their needs and concerns better. As such, we believe we obtained great value from working with older adults in this manner, and expect that we would have been unlikely to reach similar conclusions had we hosted fewer sessions.

Another advantage of hosting sessions concentrated over three weeks, as opposed to spread out over a longer period, is that it made it easier for the older adults to concentrate on the task without having to reintroduce the project.

Hosting the sessions at the retirement community where the participants live also provided advantages in making them feel comfortable and at home. In addition, by seeing and speaking with fellow participants while we were not there, participants continued to be engaged in the project, thinking about it even while we were not present.

In spite of these positives, we also found challenges with our approach. The main challenge was likely caused by a combination of cognitive declines in the participants and the fact that they spoke to each other about the project when we were not present. We found that at the beginning of every week, a few participants raised the same set of questions regarding the true objective of the project and risks to the information of the participants. They thought we may be agents of pharmaceutical companies trying to push medications, and they had concerns about how their personal health data would be used, even though we never asked them for this information.

We addressed this challenge by respecting the concerns of the participants and honestly answering all their questions. Even though we were often asked the same questions on a weekly basis and provided the same answers, we understood this to be necessary given the population we were working with.

Similar projects working with older adults should plan for time to address issues related to project goals and ethical concerns, and would likely benefit from having an upfront discussion of these issues when first engaging with a group in a similar setting.

Translating Lessons into the User Interface

Following our sessions we iteratively designed an online PHR with the purpose of obtaining longitudinal data from its use by older adults. Because we identified problems with the medication components of available PHR products, we have concentrated particularly on a module to help older adults keep track of their medications and obtain warnings related to the medications they are taking. As we have developed this online PHR based on the guidelines and specifications described above, we have consulted a separate group of older adults on three occasions, asking them to complete basic tasks with iterations of the system and obtaining feedback from them.

Keeping Track of Medications

To keep track of medications, we have followed the advice of our participants and kept the data to be entered to a minimum. Users are only asked to enter the name of the medication, which they can enter in free text or select from an auto-complete list that includes thousands of prescription and over-the-counter medications. They also can enter the strength of the medication, how they take it, and the reason they take it. See a screenshot of the user interface in Fig 1.

Our biggest challenge in this respect has been in providing a flexible auto-complete user interface that makes it easy to find medications. This is critical in order to be able to generate warnings, as medications need to be correctly identified for that purpose. The challenge is that pharmacies use different kinds of abbreviations for medicine names, with no standards.

Fig. 1. User interface to enter medications

Our current design reflects the lessons learned from concentrated sessions working with older adults, with a minimalist design that captures the most important data about medications, and thus makes it more likely that they will be entered by older adults.

Warnings

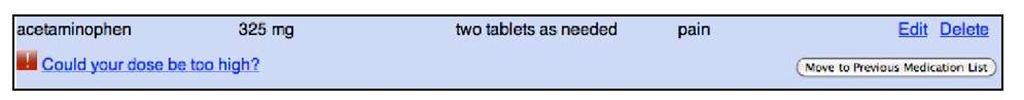

The warnings, as mentioned earlier, are provided with three different levels of detail. The first level uses just a few words and shows the warning under the name of the medication. See an example in Fig 2. This first level warning is intended to provide a general idea of the reason behind the warning. It is also meant to catch user attention, using easy to understand vocabulary.

Fig. 2. Example of first level warning showing under medication

Clicking on the first level warning pops up a window showing the second level warning. See an example in Fig 3. This second level warning provides more details as to why the warning was triggered, in this case providing basic advice on how to avoid overdosing on acetaminophen.

Fig. 3. Second level warning pops up in separate window when first level warning is clicked

Clicking on the "More ways to reduce your risk" button shows additional information on the pop up window. In the additional feedback we have obtained in the three meetings with the other group of older adults, our three-level warning approach has been well received, providing the right level of information at each point. It does not overwhelm users with all details at once, provides useful information at all levels, and enables older adults to obtain further information in case they are interested in learning more.

Use of Video for Expectations and Training

We are also making use of video to describe and present how to use our system. In our focus groups, we noticed that being able to see a very quick demonstration of how to use the system made it significantly easier for older adults to navigate and use our PHR.

Future Work

We have deployed our PHR and are currently conducting a longitudinal trial with hundreds of older adult participants to learn about how they use our PHR and about the impact of using the PHR on their use of medications. We expect this experience will help us better understand the features of PHRs that are most relevant to older adults and how these can translate into health benefits.

Conclusion

Working with a small group of older adults provided valuable insights on the design of a PHR targeted to them that would have been very difficult to obtain otherwise. We have developed a web-based PHR system based on the lessons described above. Our PHR follows a minimalist approach, tracking as little information as possible while enabling meaningful use in order to increase adoption. Our medication warnings emphasize specific recommended actions that patients can take.