1. Introduction

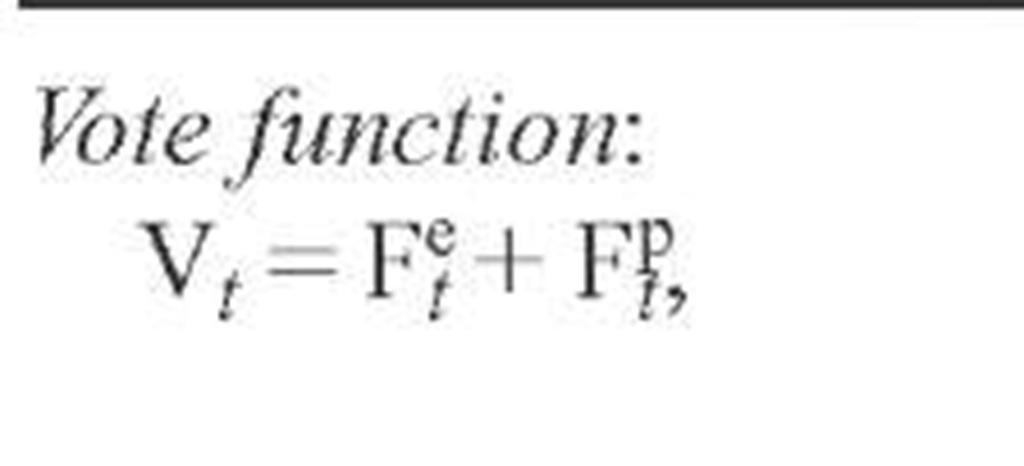

During the last 30 years about 300 papers on Vote and Popularity functions (defined in Table 1) have been writ-ten.1 Most of the research is empirical. The purpose of this article is to survey this literature and discuss how the empirical results fit into economic theory.

It is my experience that when academic economists are confronted with the results of the VP-research they frown, as they go against "our" main beliefs. Voters do not behave like economic man of standard theory. In other words, the results are not "economically correct" — as defined in Table 2. Political scientists have other problems depending on their school, so this essay is written to the typical mainstream economist (as the author).

From bedrock theory follows a remarkable amount of nice, sound theory, and everything can be generalized into the general equilibrium, growing along a steady state path maximizing consumption. Politics convert the demand for public good into the optimal production of such goods and minimizing economic fluctuations. The past is relevant only as it allows the agents to predict the future, markets are efficient etc. This nice theory is well-known, and it is a wonderful frame of reference. Especially in the 1980s a strong movement in economics argued that the world was really much closer to the bedrock than hitherto believed. If the noise terms are carefully formulated, the world is log-linear and everybody maximizes from now to infinity.

Table 1: Defining the VP-function

Table 2: Characterizing the economically correct model

Bedrock theory: Models are built symmetrically around a central case where rational agents maximize their utility from now to infinity, given perfect foresight. The key agent is termed economic man.

Bedrock theory suffers from two related problems. The first is that it is a bit dull. So many models are "set into motion" by some (small) deviation from perfection — for example an observation that seems to contradict the theory.2 It is almost like a good old crime story. A criminal is needed for the story to be interesting. However, in the end the criminal is caught and all is well once again.

The second problem is the theodicy problem of economics.3 With such rational agents we expect that economic outcomes are rational too. How come we see so many crazy outcomes when we look at the world? Average GDP differs between countries by 100 times. Some countries have pursued policies that have reduced their wealth by a 2-3% per year for several decades (think of Zambia). All countries have irrational institutions such as rent control and (at least some) trade regulation. Discrimination based upon ethnic differences is common etc. Debt crises have frequently occurred. The reader will probably agree that nobody can be closer to economic man then the bankers of the island of Manhattan: How come that even they managed to lend so much to Bolivia that at one point in time the debt burden reached 145% of GDP? We will return to the theodicy problem of economics at the end, but let us return to the subject matter.

Economic data tend to be much better — and easily accessible — than political data, so most of the literature on VP-functions concentrates on the economic part of the function. The present essay follows this tradition and uses the setup listed in Table 3.

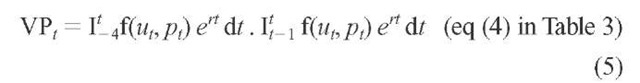

Many experiments have been made with the lag structure, plenty of economic variables have been tried, and sometimes more genuine political variables have been included,4 nonlinear functional forms have been used, etc, but we shall mainly discuss the simple linear expressions (3) and (4) from Table 3.

Table 3: The basic quarterly macro VP-function

Greek letters are coefficients to be estimated. e’s are residuals ut, pt, …, are economic variables as unemployment (u), inflation (p), etc ag and tg, the political part is reduced to a government specific constant and trend

2. Main Results in the Literature

The literature on VP-functions is large, but most of the findings can be concentrated as in Table 4. The starting point is a simple hypothesis.

The responsibility hypothesis: Voters hold the government responsible for the economy. From this hypothesis follows the reward/punishment-mechanism: Voters punish the government in votes and polls if the economy goes badly, and they reward it if the economy goes well.

The hypothesis is not without problems: Governments may not have a majority, or external shocks may occur, which no sane person can ascribe to the government. A variable giving the clarity of responsibility may consequently enter the function. This is referred to as "content" in Table 4 — a subject that will not be discussed at present.

The literature was started by Kramer (1971) writing about vote functions (in the US),5 while Mueller (1970) and Goodhart and Bhansali (1970) presented the first popularity function — for the US and UK — almost simultaneously.

The most important contributions since then are much more difficult to point out, but the following may be mentioned: Frey and Hibbs (1982) generated a wave of papers, both due to their lively fight and to new developments: Frey and .

The micro-based literature was started by Kinder and Kiewiet (1979). It was further pushed by Lewis-Beck (1988), while the cross-country discussion was started by Paldam (1991). A good sample of papers giving the present stage of the arts can be found in two recent volumes (both results from conferences trying to collect the main researchers in the field): Lewis-Beck and Paldam (2000) and Dorussen and Taylor (2002). This effort has generated the results listed in Table 4.

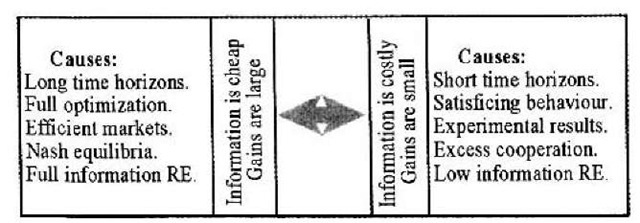

Each of the items of the table except the last will be discussed in a short section. We will argue that most are contrary to economic correctness, but that they are all possible to rationalize. However, they are at the opposite extreme of the rationality spectrum from the one normally considered by economists, see Figure 1 at the end: On one side is economic man and on the other the actual voter. This essay is written to say that this other side of the spectrum is getting far too little attention in standard theory.

Figure 1: The two ends of the rationality spectrum.

Table 4: Main results in the literature

|

Section |

Finding |

Empirical status |

|

3. |

The big two: Voters react to mainly unemployment and inflation |

Uncontroversial |

|

4. |

Myopia: The time horizon of voters is short — events more than 1 year from an election have small effects only |

Uncontroversial |

|

5. |

Retrospective: Voters react to past events more than to expected future ones, but the difference is small as expectations are stationary |

Controversial |

|

6. |

Sociotropic: In most countries voters are both sociotropic and egotropica |

Controversial |

|

7. |

Low knowledge: Voters know little about the (macro) economy |

Uncontroversial |

|

9. |

Grievance asymmetry: Voters punish the government more for a bad economic situation than they reward it for a similarly sized good one |

Controversial |

|

10. |

Cost of ruling: The average government ruling a normal 4-year period loses 22% of the votes. This result is independent of party system, voting law, country size, etc |

Uncontroversial |

|

Not covered |

Context: The VP-function only generalizes if set in the same context. In particular, the responsibility pattern generalizes if the government is clearly visible to the voter |

Only explored in a dozen papers |

Note: The status line indicates if the result is controversial, i.e., if a minority of the researchers in the field disagrees. The article only considers the responsibility pattern and thus assumes a simple setting where both the government and the opposition are well defined. Complex, changing coalitions and minority governments are not discussed. a Sociotropic: voters care about the national economy. Egotropic: voters care about their own economy.

In Table 3 the models are written as simple relations between levels, assuming all variables to be stationary. The present will largely disregard the substantial problems of estimation. That is, (i) should the model be formulated in levels or in first differences? (ii) should it contain an error correction term? And (iii) should series be pre-whitened? Popularity series are known to have complex and shifting structures in the residuals when modeled. So there are plenty of estimation problems. Many of the papers are from before the cointegra-tion revolution, but new papers keep coming up using state of the arts techniques, though they rarely find new results.

Politologists have found that only 20% of the voters in the typical election are swing voters, and the net swing is considerably smaller, see Section 10. It means that 80% vote as they always do. The permanent part of voting is termed the party identification, Id. It is not 100% constant, and it needs an explanation, but it should be differently explained from the swing vote. The VP-function concentrates on the swing voters, but it may be formulated with terms handling the more permanent part of the vote as well.

In the more simple formulations one may work with level estimates where the committed voters enter into the constants, and with the first difference estimates where the committed voters are "differenced out". The choice between the two formulations is then a question of estimation efficiency to be determined by the structure of cointe-gration between the series, and the (resulting) structure of the error terms.

3. The Big Two: Unemployment (Income) and Inflation

The two variables which are found in most VP-functions are the rates of unemployment and inflation, ut and pt. Both normally get negative coefficients, often about -0.6 as listed in model (4) of Table 3. Unemployment is sometimes replaced with income thus confirming Okun’s law. The Phillips curve is sufficiently weak so that unemployment and inflation have little colinearity in these functions.

The data for the rate of unemployment and the vote share for the government have roughly the same statistical structure so that it is possible that they can be connected as per the linear version of model (1). Data for the rate of inflation are upward skew. That is, inflation can explode and go as high as the capacity of the printing press allows. Also, people pay little interest to low inflation rates, but once it reaches a certain limit it becomes the key economic problem.6 Hence, inflation cannot enter linearly in model (1), except of course, if we consider a narrow interval for inflation rates. Fortunately, inflation is often within a narrow interval in Western countries.

An interesting controversy deals with the role of unemployment. It was started by Stigler (1973) commenting on Kramer (1971). Stigler remarked that a change of unemployment of 1 percentage point affected 1% of the workers only — that is 2% of the population. App 80% of those vote for the Left anyhow. The potential for affected swing voters is thus only 0.1% of the voters. How can this influence the vote by 0.6%? Note that Stiegler automatically assumes that voting is egotropic and retrospective. You change the vote if you — yourself — are affected by the said variable.7 This point deals with the micro/macro experiences and the observability of the variables. It has often reappeared in the literature. Table 5 shows some of the key points.

The table lists the important variables and some other variables that have often been tried, but with little success. Unemployment and income affect individuals differently and are observable both at the micro and the macro level. Inflation is more difficult to observe for the individual at the macro level. We see prices go up, but the individual cannot observe if they rise by 2 or 3%. However, this is covered by the media.

The other variables listed — the balance of payments and the budget deficit — are much discussed in the media and are important in political debates. They are important predictors for policy changes, and indicators of government competence. However, they have no micro observability. It is interesting that they are rarely found to work in VP-functions.

Table 5: The character of the variables entering in the VP functions

|

Micro-experience |

Observability |

Significant |

|

|

Unemployment |

Very different for individuals |

Personal and media |

Mostlya |

|

Income |

Different for individuals |

Personal and media |

|

|

Inflation |

Similar for individuals |

Mostly media |

Mostly |

|

Balance of payment |

None |

Only media |

Rarely |

|

Budget deficit |

None |

Only media |

Never |

aThe two variables have strong colinearity in VP-functions.

Refined models with competency signaling and full information rational expectations, where voters react to predicted effects of, e.g., budget deficits, are contrary to the findings in the VP-function literature. In fact, when we look at what people know about the economy — see Section 7 — it is no wonder that they do not react to changes in the balance of payments and the budget.

Under the responsibility hypothesis model (1) is an estimate of the social welfare function. It comes out remarkably simple. Basically, it is linear, and looks like Model (4) in Table 3. The main problem with such estimates is that they are unstable. Many highly significant functions looking like (4) have been estimated, but they frequently "break down" and significance evaporates.

If (4) is stable, it appears inconceivable that it cannot be exploited politically. And, in fact a whole literature on political business cycles has been written — since Nordhaus (1975) exploring the possibility for creating election cycles in the economy. However, most studies have shown that such cycles do not exist in practice. What may exist is rather the reverse, governments may steer the economy as per their ideology and create partisan cycles.8

4. Voters are Myopic

The voter’s myopia result deals with the duration of the effect of a sudden economic change. Imagine a short and sharp economic crisis — like a drop in real GDP lasting one year — how long will this influence the popularity of the government?

One of the most consistently found results in the VP-function literature is the voter’s myopia result. Only the events of the past year seem to count. A few researchers (notably Hibbs, 1982) have found that as much as 3 of the effect remained after 1 year, but most researchers have been unable to find any effect after one year. The myopia result has been found even for political crises, which are often sharply defined in time. Consequently, the model looks as follows:

The subscript (t -1) represents a lag of one quarter (or perhaps one year) as before. The welfare maximization of the variable u (say unemployment) leading to the vote is made from t- 1 to t, where the time unit "1" is a year, and the "discounting" expression ert has a high discount rate so that everything before t- 1 is irrelevant.

Formula (5) is surely not how such expressions look in economic textbooks. A key part of economic correctness is that economic man has a long time horizon and looks forward. The common formulation of the closest corresponding models is:

The welfare to be maximized is a function of the relevant economic variable from now to infinity, with a small discount rate, r, perhaps even as small as the long run real rate of interest or the real growth rate. It gradually reduces the weight of future values, but events 20 years into the future count significantly.

Expressions (5) and (6) are hard to reconcile. First, the maximization is retrospective in (5) and prospective in (6), as will be discussed in Section 5. Second, the time horizons are dramatically different. None of the 300 studies have ever found evidence suggesting that events as far back as 2 years earlier have a measurable impact on the popularity of the government!

Many descriptions have been made of the political decision process by participants in the process and by the keen students of current affairs found among historians, political scientists and journalists. A common finding is that the decision process tends to have a short time horizon. The political life of a decision maker is uncertain and pressures are high. How decisions are made has little in common with the description of "benevolent dictators maximizing social welfare" still found in economic textbooks and many theoretical models.

The outcomes of "benevolent dictator calculations" have some value as a comparative "benchmark", and as ideal recipes for economic policy making.9 However, some theorists present such exercises as realistic descriptions of policy making, deceiving young economists into believing that this is the way political decisions are made.

5. Voters are Retrospective/Expectations are Static

One of the key facts about economic theory is that it is largely theory driven. One of the main areas over the last 4 decades has been the area of expectation formation. It has been subjected to a huge theoretical research effort. Less interest has been given to research in the actual formation of inflationary expectations where real people are actually polled, as the results have typically been embarrassing. I think that we all know in our heart of hearts that real people cannot live up to our beautiful theories about economic man.

In the field of VP-functions about 50 papers have looked at the existing data and found that in many countries RP-pairs — defined in Table 6 — have been collected for such series as unemployment, inflation and real income. The papers have then tried to determine which of the two variables in the pair are the most powerful one for predicting the vote/popularity of the governments.

Table 6: A polled RP-pair

|

Economics |

Politology |

Question in poll |

|

Past experience |

Retrospective |

How has X developed during the last Z-period? |

|

Expectations |

Prospective |

How do you expect X will develop during the next Z-period? |

Note: X is an economic variable and Z is a time period like a quarter, a year or a couple of years.

Most of the analysis is done on micro-data of individual respondents, so many thousands of observations have been used to determine this controversy. The many papers do not fully agree, so the results of the efforts have to be summarized as follows:

RP1: The two series in the RP pair normally give almost the same results.

RP2: Most results show that the retrospective series are marginally more powerful.10

I think that virtually all economists will agree that the correct result in the RP-controversy is that the prospective twin should beat the retrospective one by a long margin. But by a rough count the retrospective twin wins in 2 of 3 cases in the studies made.

Some of the main discussants in this research are Helmut Norpoth for the majority retrospective view and Robert S. Erikson for the minority prospective view. They are working with the same data for the USA. Erikson terms the controversy bankers or peasants. Bankers work professionally with the economy and have prospective expectations. Peasants are interested in matters of farming mainly, and hence are retrospective, when it comes to the economy. The question thus is, if the average voter behaves mostly as a banker or as a peasant.11 Once the question is asked, it appears that the obvious answer must be that the average person is a peasant. However, Erikson finds that voters behave as bankers.12

When the results of Erikson and Norpoth are compared, the difference is small. The most disgraceful result actually is (RP1) that the two series in the existing RP-pairs are as similar as identical twins. The only conclusion one can draw is that people form largely static expectations.

The author’s own poll of 4788 Danes asking about the RP-pair for inflation found a net difference in the answers of 34 cases, i.e., 0.7% of the respondents (see Nannestad and Paldam, 2000).13 With such a tiny difference it is no wonder that we were unable to find any difference in the fit of the VP function if we used the prospective or retrospective series. This is typical also for the British and the German results.

This brings us back to the large gap separating formulas (5) and (6). It does solve the apparent contradiction between the direction of the maximization if voters have static expectations. But then surely it is much easier to use the past as in (5). When we look at the vast literature building highly refined theory of inflationary expectations and analyzing the dynamic consequences of the different assumptions it is hard to reconcile with the findings of the VP-literature. Here is surely a field where facts are much duller than fiction.