INTRODUCTION

As communities develop their sense of identities, the Web reflects such identities through the appearances of Web portals. This short article argues that it is not only technologies that drive the emergence and popularity of portals, but the very sense of commonality that communities share fuels and propels the development and growth of portals. Such commonalities contribute to the establishment of a “knowledge commons” within the community; a virtual space dedicated to the sharing of understanding, memory, and practical know-how. Using a case study of a portal developed for the purpose of producing “advertainment” content in the upcoming Beijing Humanistic Olympics, the role of portals in contributing to the establishment of the knowledge commons is investigated.

This article centres its discussion around the case of the portal developed for the purpose of the upcoming Olympics in Beijing, 2008, and examines the ways by which the portal has been set up to cultivate memories of the event by cross-cultural communities. This article explores how technology and action by many people are aggregated and organised by the portal to create a knowledge commons space for the communities involved.

The idea of a commons is not new—in fact it has always been around—as long as the first human cooperation in history. Men hunting together for food and sharing their skills and eventually, their produce—the commons is rooted in communities of social trust and cooperation (Bollier, 2004).

Since its conception, the commons have received a faire share of sceptics and support. Sceptics refer to it as merely a metaphor—and regard it as risky to guide decisions based on a metaphor. Others defend it fiercely—knowing that without which, resources would be taken over by market forces. The commons, therefore, is distinct from the market. Active defenders of the commons such as the Friends of the Commons (2004) report on the status of identified commons in America. According to them, the commons “is a generic term, which embraces all creations of nature and society that we inherit jointly and freely, and hold in trust for future generations.” Levine (2002) points out the “commons” as resources that are not possessed or controlled by any one individual, company, or government. These resources are un-owned and therefore, free for all to use, borrow, imitate, or alter.

Such defenders argue that it is critical that we make distinctions between what is shared and common to the society—so as not to allow market forces to overwhelm the less privileged—and create fragmentations caused by social differences such as income and literacy. While the commons movement has been historical, the current movement of the knowledge commons focuses on knowledge creating communities using technologies to empower or constrain their shared spaces and resources. This article examines how portals can play a part toward this movement.

The portal in discussion is part of the collaboration-production trial project that runs within the framework of “sustainable Olympics” where teams from past, current, and future Olympic cities collaborate over the Internet to contribute in the creation of all types of multimedia content resources representing the participation of volunteers in the past and upcoming Olympics.

Salient to this article is the approach to consider community cultures as a starting ground to illustrate the drivers and motivations behind portals and their emergence, cohesion, popularity, and interactivity. Using Gidden’s struc-turational theory (1986), this article first demonstrates how portals provide for communities senses of identities and in that context, how a knowledge commons space is created within the portal.

PORTALS IN THE CONTEXT OF KNOWLEDGE-CREATING COMMUNITIES

While it is clear that there are already many examples of portals—bringing together structured collections of resources, communities, and technological applications, Strauss (c.f. Pearce, 2003) stated that there appears to be a trend of “portalisation” where organisations “are rushing to produce portalware and portal-like Web pages without fully understanding the scope of a portal undertaking.” Pearce (2003) provided further understanding to this seemingly confusing trend, noting that portals have evolved to be expected to perform a number of diverse functions, including the access, storage, and organisation of information, gateway to enterprise applications, customer relationship management, communication, and so on. This article argues that the sustainability and usefulness of portals lies in the dynamics of the user communities; and in the same way, portals function as an important platform for the sustain-ability of communities.

Figallo (1998) states that true community exists when “a member feels part of the larger social whole,” when “there is ongoing exchange between members of commonly valued things,” when there is an interwoven Web of relationships between people, and when these relationships last through time, creating shared meanings and histories.

It is an opportunity that portals present in bringing together the construction of self and communal knowledge of individuals and their communities. The emergence and popularity of portals is evidence of a desire of people in a community to connect, alongside with the need to construct self-knowledge. This desire, or innate nature of people, is described by Castells (2003) as:

We know of no people without names, no languages, or cultures in which some manner of distinctions between self and other, we and they, are not made…Self-knowledge—always a construction no matter how much it feels like a discovery—is never altogether separable from claims to be known in specific ways by others. (Castells, 2003)

According to Castells (2003), the construction of self-knowledge is an inevitable process when people come together as a community. The term “communities” is used in its widest sense here, including communities of practice, communities of interest, local and virtual communities (Wellman&Haythornthwaite, 2000; Wenger& Snyder, 2000). The term covers not only corporate-based communities, but also the vast variety of communities that make up the civil society as defined by the World Summit on the Information Society (Schauder, Johanson, & Taylor, 2005). The ties that bind people together is well above and beyond their formal tasks and work practices. As noted by Figallo (1998) and Rheingold (2002), there is a view of communities that is altogether dialectic and multifaceted.

In the process of self-construction of knowledge, one makes sense of his or her existence, presence, and roles in the world—and in this process of constructing knowledge of oneself, people in communities make sense of their relationships with other people (whether through work or otherwise), and thereby end up with multiple associations with various communities–and very often the behaviour and roles they eventually take up in different communities are not independent of each other. Because there is such a multiplicity and intertwine of communities consciousness in people, whether they are made aware or not, it is not possible to only include one aspect of a community without considering the others.

The world ends up with people trying to make sense of their identities in multiple communities, reducing the conflict between these identities, and eventually results in a glut of communities trying to collaborate within and with each other, and in the course of trying to achieve this aim, technology, spaces, and other resources are utilised. With the current state of the Internet and information society, we are already witnessing how that can be an extremely chaotic (and sometimes trying) task.

Portals provide access to information technologies, resources, and contexts of use—they also provide a method by which such multiple layers of identities, memories, and knowledge can be construed by communities. In examining the social reality of portals, they are regarded as forms of structure (Orlikowski & Robey, 1991)—created by and shaping human actions. The consideration of human actions must therefore be examined with the dynamics of communities in mind. With this in mind, the article evaluates a vision of portals using structurational theory.

Giddens (1984) offers the insight that:

The best and most interesting ideas in the social sciences (a) participate in fostering the climate of opinion and the social processes, which give rise to them, (b) are in greater or lesser degree entwined with theories-in-use, which help to constitute those processes, and (c) are thus unlikely to be clearly distinct from considered reflection, which lay actors may bring to bear in so far as they discursively articulate, or improve upon, theories-in-use. (Giddens, 1984, p. 34)

In other words, meanings, actions, and structures are closely and continuously interdependent. The cumulative effect of people’s living and working within social frameworks (through a dynamic that Giddens calls structuration) is the production and re-production of culture. According to Giddens, community cultures are generated and re-generated through the interplay of action and structure. Social structure both supports and constrains the endeavours of individuals, communities and, societies. Giddens’ theory of structuration is the cornerstone concept for this article.

In Giddens’ theory of structuration, he proposes what is known as the “duality of structure,” where human actions create structure or institutional properties of social systems, which in turn shapes human actions (Giddens, 1986). It recognises that “man actively shapes the world he lives in at the same time it shapes him” (Giddens, 1984). Information technology is well posited in the theory of structuration—its very nature reflects an underlying structurational duality: where human actions, the needs, wants, skills, and collaborative tasks of communities create requirements for technological systems, and with these such structures, shapes human actions.

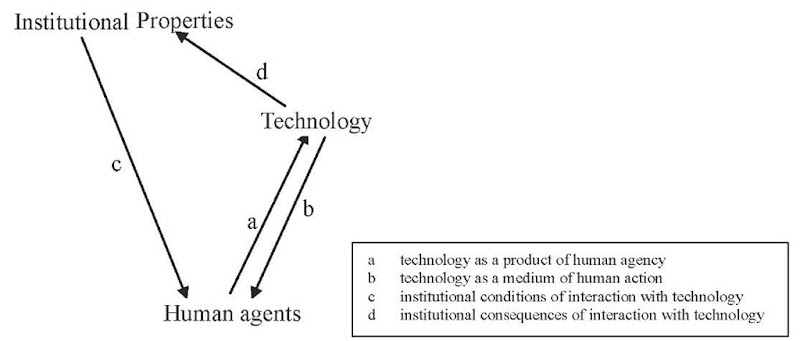

Portals, when considered as an object of study, require constantly renewed effort at definition depending on context. It is now a reality of the techno-social condition that people need to grapple continuously with the multiple personae of portals and their enabling functions. Clearly, this interaction with portals needs to be accounted for. Orlikowoski (1992) depicts a recursive model of information technology using structuration theory; applied to a vision of portals in this article (Figure 1).

The recursive nature of technology based on structuration theory is reflected in the structurational properties of portals as being created and changed by human action, but also both supporting and constraining such actions. Through such interplay, the memories of people are cultivated—created and used by the portals in use.

THE CASE OF THE BEIJING HUMANISTIC OLYMPICS (2008)

Under the commission of Humanistic Olympics Studies Centre for Beijing Olympics 2008, and with support from China StateAdministration of Radio, Film, and TV (SARFT), a team in CUC (Communication University of China), also a member of METIS Global Network (www.metis-global.org), the cross-cultural research organisation in multimedia studies, began working on the project of producing an “advertainment” (so called because the production would implicate the purpose of entertainment and advertising, whether commercial or not) portal for use in the Beijing Olympics.

The intended use of this portal was to allow volunteers, spectators, or any other participants of the Beijing Olympics to upload self-directed video clips and relevant advertisement clips associated with the event to the portal. Access to these resources is facilitated through a Web interface in the portal, and access to the portal is open to all interested participants of the event. This could include local and international volunteers of the Beijing Olympics (2008), spectators, and business sponsors. A prototype of this portal is being developed at present, optimised for streaming media content delivery.

Given this context of use, the portal provides for the communities of volunteers, spectators, and participants of the Olympics a space for them to collaborate, share resources, and communicate. There are various reasons for them to do so—most of which are associated to their desire and sense of belonging to the causes of the event.

The notion of “advertainment” as the emphasis of the portal presents a case of an innovative portal that is born out of an age of convergence—as described by Price Waterhouse Coopers (2006) to refer to the ability of different network platforms to implement different services and the merger of consumer devices. In the case of the portal, this would translate into layers of meanings and constructions, some of which are embedded in information objects. This in turn, results in the special treatment of information objects being deployed and redeployed in the functions of the Web site.

The idea of multiple memberships is introduced with each content object as potentially belonging to, or used by more than one entity. Different observers or users would evaluate the same content object based on diversified experience and knowledge, resulting in inconsistency of content features. Users from diverse backgrounds and cultures, of various religions, disparate social classes, could view a same colour with dissimilar sentiments.

Figure 1. Structurational model of technology

This assumption supports the precondition of the commons—where no resources are owned or controlled by a single entity and are shared by people in communities. The approach to developing metadata for information objects and resources is also intricately designed to allow users to define their own tags to the multimedia objects they are creating and sharing in the portal, while including in the description model of the portal’s infrastructure, to manage uncertainties in such metadata. The rationale for including this logic is also based on the assumption that resources in the knowledge commons are not controlled or manipulated by any one individual, organisation, or business entity; there is a high level of uncertainty to which contents could be described.

The main component of the portal lies in the sharing of resources by the community, which cultivate shared memories of the event. Public video captures of various members are shared with others, and through these shared resources, the sharing of stories on viewing the same event in the Olympics are elicited. At the same time, advertising videos are put up and shared by the business stakeholders, facilitating further identifications with the event as a whole, and cultivating further memories of the event as a community.

COMMUNITIES ON THE SAME BENCH: THE CASE FOR THE KNOWLEDGE COMMONS

The idea of having a portal advocating advertising values may trigger arguments that advertising and commercial sponsoring oppose the development of the commons (Levine, 2002). However, Bollier (2004) highlights that the commons is not necessarily unsympathetic to the market. In his article, Bollier (2004) points out both are needed to “invigorate each other’—in other words, inspiring and supplement each other. In the example of the open source vs. proprietary software, while one encourages creativity, learning, and accessibility to knowledge, the very culture of such environments inspires and promotes marketability.

In the case discussed, the notion of “advertainment” is one that seeks to advocate a healthy inclusion of market forces. Information objects are seen to include advertising or entertainment (or possibly, both) values; and whether they originate from commercial sources are of little importance. The emphasis in this portal lies in the sharing of memories of the event from cross-cultural communities, of which commercial entities are a part.

The article has so far discussed a view of portals that is necessary for their sustainability—one that sees portals as not being driven by technologies or even accessibility, but sees portals as driven by the identities, resources, and spaces that people in communities share with each other. This concept of sharing and inclusion of community dialogue is congruent with the concept of the knowledge commons.

Communities are seen working and coming together for the production of knowledge, using portals (as viewed through the lens of structuration theory) as tools to facilitate the construction of knowledge and cultures. As with the knowledge commons, communities see themselves not merely as users and exchangers of information, but in themselves coming together to contribute to the knowledge commons belonging to the community. Portals provide such a space for this interplay and interaction; and in the process, establish a knowledge commons space consisting of both physical and virtual dimensions.

CHALLENGES AND FUTURE WORK

Although the concept of the commons is not new, there has been a considerable amount of interest in looking at it as a framework for considering the dynamics of communities and the successful design (and redesign) of technological applications and workspaces. More work calls to be done requiring empirical research findings from community and organisational case studies. The knowledge commons movement also calls for radical rethinking of design methodologies to guide the design and developments of portals and informational resources accessed through portals.

Conclusion

The article has discussed, in the case study of a portal developed for use in the upcoming Olympics in Beijing (2008), the inclusion and consideration of communities’ dialogues and their cultures as a design precondition for portals. Given the nature of the event, the portal is designed to use a variety of multimedia formats to enable the creation and cultivation of memories of the event by the communities. This article discusses the key features of the portal to capture stories (through rich multimedia formats) of the event and through the sharing of these events, cultivate memories of the event for cross-cultural communities. The support of collaborative tasks is one other key feature of the portal, which again, supports the larger goal of cultivating cohesiveness and establishing a commons within the diverse communities of the Olympics.

KEY TERMS

Advertainment Portal: Aportal designed for the purpose of the Humanistic Olympics event to be held in Beijing, centred on the purpose of capturing stories and memories of the event from various communities. These memories are captured in rich multimedia formats, and contain advertising, entertainment (or both) value.

Communities: The term “communities” is used in its widest sense here, including communities of practice, communities of interest, local and virtual communities. The term covers not only corporate-based communities, but also the vast variety of communities that make up the civil society.

Convergence: As defined by Price Waterhouse Coopers (2006), the term “describes two trends.” One, the ability of network platforms such as broadcast, satellite, cable, telecommunications to deliver similar services, and two, the merger of consumer devices (telephones, televisions, PCs, mobile phones). Previously distinct media distribution channels are broken down in the age of convergence.

Culture: Referring to a system of shared beliefs, values, customs, behaviours, and artifacts that members of a group use to make sense of the world and with one another. Cultures are viewed as transmitted from one generation to another, through memories, artefacts, and stories told to one another.

Humanistic Olympics: The Humanistic Olympics concept was developed in 2003, and looks to developing the Olympics event in relation to morality and cultural themes. It signifies the upholding of the Olympic spirit amidst economic globalisation and aims to bring together cross-cultural values in the event.

Knowledge Commons: Derived from the historical commons, the knowledge commons refer to spaces within which communities can exercise freedom from constraints imposed by functional markets for the creation and sharing of knowledge–using technologies and resources toward this purpose.

Structurational Theory: A social theory developed by Giddens (1986) addressing the classic structure/actor dualism.

Streaming Media: Refer to rich media such as sounds and moving pictures transmitted over the Internet in a continuous or streaming fashion, using segments of data packets.