INTRODUCTION

The demand of a rich suite of easy-to-use tools and help that simplify data management within a network is increasing more and more. These tools should give users immediate access to resources, and control over when and how they share information (Portals & Gateways references, 2006). This article:

• discusses the benefits and limitations of portals;

• mentions the different types of portals;

• introduces their advantages as well as their limitations; and

• concludes with conditions important for users’ satisfaction.

WHAT IS A PORTAL?

Web portals are sites on the World Wide Web that typically provide personalized capabilities to their visitors. They are designed to use distributed applications; different numbers and types of middleware and hardware to provide services from a number of different sources. In addition, business portals are designed to share collaboration in workplaces. A further business-driven requirement of portals is that the content be able to work on multiple platforms such as personal computers, personal digital assistants (PDAs), and cell phones (Wikipedia, 2006).

Commonly referred to as simply a portal, a Web site or service that offers a broad array of resources and services, such as e-mail, forums, search engines, and online shopping malls. The first Web portals were online services, such as AOL, that provided access to the Web, but by now most of the traditional search engines have transformed themselves into Web portals to attract and keep a larger audience (We-bopedia, 2006).

As defined by IBM, an Internet portal is “a single integrated, ubiquitous, and useful access to information (data), applications and people.” A portal may look like a Web site, but it is much more. The latter, while an important part of any university’s communications strategy, is primarily a way to provide static information (Richard N. Katz and Associates, 2006, chap. 8).

THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF PORTALS

There are several kinds of portals:

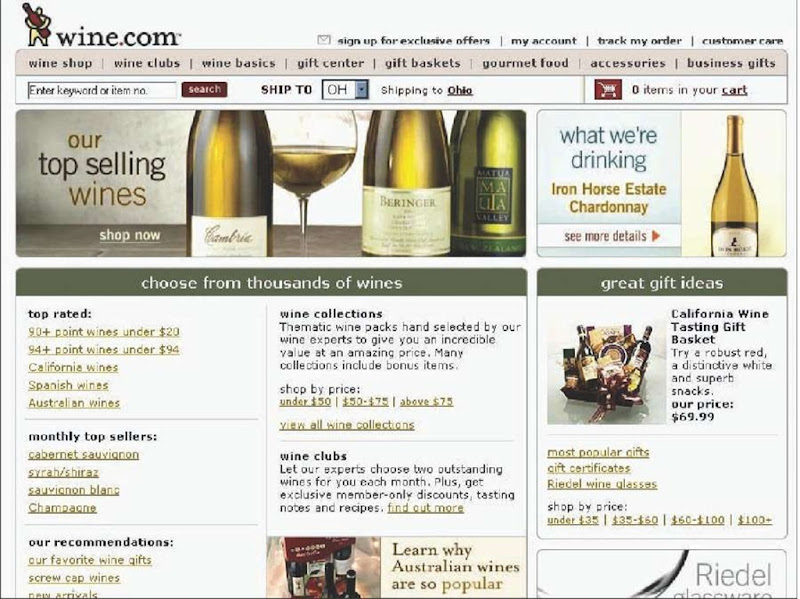

• Vertical Portals: Provide access to a variety of information and services about a particular area of interest. For example, http://www.wine.com is a vertical portal. Such portals offer information and services customized for niche audiences (e.g., undergraduates, faculty).

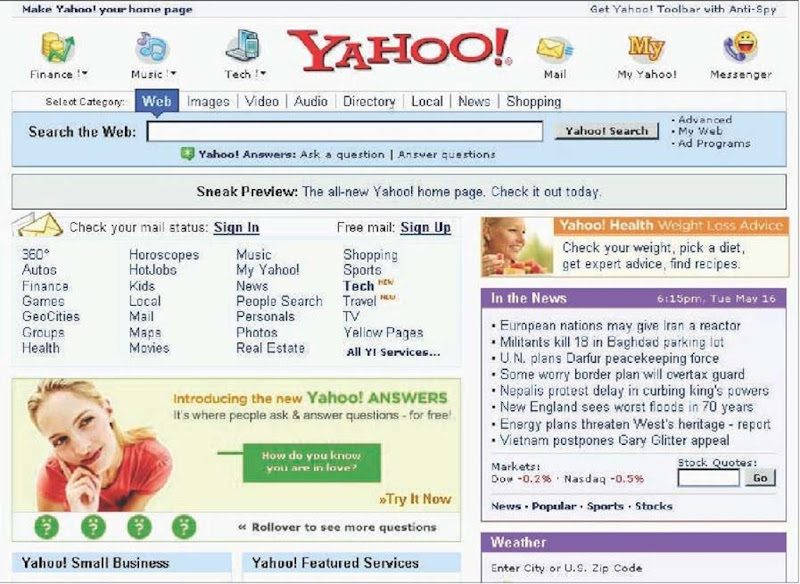

• Horizontal Portals: Often referred to as “megapor-tals,” target the entire Internet community. Sites such as http://www.yahoo.com, http://www.lycos.com, and http://www.netscape.com are megaportals. These sites always contain search engines and provide the ability for a user to personalize the page by offering various channels (i.e., access to other information such as regional weather, stock quotes, or news updates). Providers of megaportals hope individual users go to their sites first to access the rest of the Internet. Their financial models are built on a combination of advertising and/or “click-through” revenues.

Enterprise portals can be either:

• Vertical: Focusing on a specific application such as human resources, accounting, or financial aid information; or

• Horizontal: Offering access to almost everything an individual user within the enterprise needs to carry out his or her function. Authentication and access are based upon the role or roles the individual plays in the organization. Horizontal enterprise portals (HEPs) are customizable and personalizable. If properly designed, they can replace much of the user’s computer “desktop.”

WHY ARE PORTALS IMPORTANT?

A portal provides Internet users with a single, customized entry point to network-based campus. In the higher-education context, the portals of most interest are horizontal, that is, they are designed to offer access to almost everything that an individual user associated with the campus needs to manage his or her relationship with the University. These users can include students, faculty, staff, parents, prospective students, alumni, and members of the community at large.

Figure 1. Example of vertical portal

Figure 2. Example of horizontal portal

Ultimately, all universities will use portal technology; it is when and how that are difficult questions. Motivations for deploying a portal can include increased productivity, improved communication, possible revenue generation opportunities, and the prospect of building a stronger relationship within and among our constituents. One potential benefit is that many of the technical issues that are addressed by a portal implementation, including authentication, authorization, and security, are aligned with the existing objective to improve the technology infrastructure both within and among our campuses (Richard N. Katz and Associates, 2006, chap. 8, p. 1).

THE ADVANTAGES OF PORTALS

Regardless of whether the campus is looking for recognition, for ease of operations, for productivity gains and cost savings, or a combination of all of these, the portal will succeed or fail based upon the perceived benefits to the university community. Theoretically, every member of the university community should benefit from the portal. It should make it easier and more efficient for every individual to carry out his or her role in the institution.

One obvious reason to deploy portals is to improve productivity by increasing the speed and customizing the content of information provided to internal and external constituencies, similar to groupware applications. Portals also serve a knowledge management function by dealing with information glut in an organized fashion. In some ways, portals offer a technical solution, but not a total answer, to knowledge management. (Richard N. Katz and Associates, 2006, chap. 8, p. 5).

University portals can be a means for establishing a long-term relationship with the institution. They not only make it easy to do business with the institution, but they allow for interaction and collaboration among students, faculty, staff, and graduates with similar needs and interests. Properly implemented, portals can be a strategic asset for the institution. In that sense, they do far more than a traditional Web site of static information ever could.

Beyond institutional gains, portals offer obvious benefits to students, faculty, staff, and external stakeholders.

Students benefit from:

• Web interface to courseware and required information about courses;

• increased and easier communications with faculty;

• online access to grades, financial aid information, class schedules, graduation checks;

• access to the communities of interest within the university, sports, clubs, and community services opportunities; and

• increased life-long learning opportunities.

Faculty and staff benefit from:

• real-time communications with students;

• simplified course management tools;

• instant access to information for advising students; and

• easily accessible information for every facet of their job (Richard N. Katz and Associates, 2006, chap. 8, p. 6).

More generally, a portal, often called portal software, is a Web-based application that brings audience, application, systems and processes together to form a centralized collaboration experience. Portal software integrates technologies to build personalized work areas and communities to increase productivity for users. Portal software is built for corporate intranets, extranets, communities, Web sites, and projects, just to name a few. Depending on the kind of business needs and the portal software, one can expect to gain several benefits from using portal software in any environment. Some of the benefits are (Chozam, 2006):

• efficiently deliver information to the audience;

• increase productivity for the end user;

• provides customizable features and development tools;

• increase interaction between customers and employees;

• personalized environments for end users; and

• integration of external applications and services by portlets.

These are just several benefits that may be achieved by implementing portal software for any business (Spence & Noel, 2005).

WHY ARE UNIVERSITIES IMPLEMENTING PORTALS

Englert (2003) gives the following reasons to why universities are implementing portals. These are to: integrate/streamline information and services; improve service to students/ staff; offer personalised/customised/targeted service; improve administration efficiency; attract students;

• enhance university image/raise profile;

• engage/connect/build community; and

• offer distance/flexible learning.

DIFFERENT METHODS OF DEVELOPING PORTALS IN UNIVERSITIES

University portals can be developed in several ways (Ja-fari & Sheehan, 2003). Each has its own advantages and disadvantages. The most straightforward option is to work with one of the university’s existing suppliers that have a portal offering. The other option is to acquire a portal from a specialist vendor. The third option is to develop the portal in-house. The main benefit of this approach is the complete control it offers. Universities that plan to develop their portals in-house now have the opportunity to base their development on open-source products. This helps to speed up development time and reduce the cost.

When designed properly, a portal can improve the activities required to facilitate, manage, and assess learning. A portal can help teachers and students to discover new learning content and to express ideas in more innovative ways. It can streamline workflow and automate manual tasks. Fundamental portal capabilities include content aggregation, application integration, user authentication, personalisation, search, collaboration, Web content management, workflow and analysis, and reporting (Connect, 2004).

Typically, university portals can be grouped into institutional portals and subject-based portals (Franklin, 2004). The institutional portal provides its users with a wide range of services, integrating these through a common interface regardless of whether particular services are provided by the institution or not. An institutional portal contains information about the user, enabling it to customise itself and be customised to the individual’s interests and responsibilities. A subject-based portal brings together a variety of information sources and tools about a common theme, but is unlikely to have much information about the user.

THE LIMITATIONS AND DRAWBACKS OF PORTALS

The portal industry is several years old, and vendors come into and out of the market every month. Since typical licensing and development costs are several hundred thousand dollars or more, vendor selection is high risk. (In addition to some eight major vendors, a higher-education consortium is in the process of developing an open framework called the JA-SIG portal.) The current volatility of the portal market and the lack of agreed upon standards argues for institutions to wait to jump into a portal unless there is a clear need or benefit that requires one.

Developing a campus portal is a key strategic technology decision that will impact the entire campus community and every other strategic technology program such as CMS. The decision on a portal strategy requires careful analysis of long-term and short-term needs.

Campuses that do intend to begin the process of developing a portal need to consider the following issues:

• What short-term problem does the campus intend to solve with a portal, and is a portal the best solution?

• Is executive management willing to mandate a single portal for the campus?

• Does executive management understand that a portal represents an ongoing commitment rather than a onetime investment?

• Who owns and manages the portal?

• Is advertising appropriate? E-commerce?

An emerging consensus regarding portal development includes the following major best practices and considerations:

• there should be one and only one horizontal portal on campus;

• portals should be developed iteratively;

• the portal should support “single sign-on”; that is, with a single user id and password, each user can access all the applications and data that she or he is allowed to use;

• campuses should consider integration with both legacy systems and CMS;

• courseware management tools should be integrated with the portal; and

• while revenue generation should not drive the development of a portal, the design should allow advertising and e-commerce if desirable and appropriate.

In addition, careful consideration of security, privacy, and protection of intellectual property must be part of the portal development process.

THE USES OF PORTALS

An analysis of the different opinions indicate the following elements must be present before a Web site could be called a portal:

• Single Access Point: A single gateway or logon to identify approved users, making it unnecessary to sign onto each of the different systems that provide portal content, for example, the e-learning facility, or full- text content such as digital journals or other sources of information.

• Internet Tools: These are site search and navigation tools to provide users with easy access to information. Examples are calendars and planners to allow users to input and share events, as well as Web-site and content builders, offering them the ability to create and have customised content being made available according to individual profiles.

• Collaboration Tools: These include e-mail, threaded discussions, chat, and bulletin board software that offer a whole range of ways to communicate and share information

• User Customisation: A typical portal prompts the first-time user via a series of fill-in windows to provide information about him/her. This is then stored in the portal’s database. When that user authenticates to the portal, this information determines what he/she will see on the home page immediately after login.

• User Personalisation: A portal enables the end user to take customisation one step further, namely to subscribe and unsubscribe to channels and alerts, set application parameters, create and edit profiles, add or remove links, and many more (Van Brakel, 2003, p. 5).

Users’ Satisfaction

Bevan described satisfaction as a combination of comfort and acceptability of use: Comfort refers to overall physiological or emotional response to user of the system (whether the user feels good, warm, and pleased, or tense and uncomfortable). Acceptability of use may measure overall attitude towards the system, or the user’s perception of specific aspect, such as whether the user feels that the system supports the way they carry out their tasks, do they feel in command of the system, is the system helpful and easy to learn.

In 2001, Zazelenchuk conducted a usability evaluation study of the OneStart portal as part of his dissertation research. Forty-five undergraduate School of Education students participated, completing a series of tasks that required location information and personalising the portal system. Specifically, students had to locate certain channels of information, such as their course schedule or the campus newspaper, add them to their portal pages, and change the arrangement of certain channels in their pages to match a given sample (Zazelenchuck & Bolind, 2003).

Efficiency of Use

On the surface, the relationship between the time spent completing tasks and users’ satisfaction may seem obvious: a well-designed, responsive system provides a more efficient experience and greater satisfaction. Indeed, earlier satisfaction research with client-based systems confirmed that system response time contributes significantly to user satisfaction. More recent studies, however, question the correlation between users’ efficiency and satisfaction, because users have demonstrated preferences for systems with which they performed less efficiently. This raises the question of how well efficiency relates to user satisfaction for recent technologies, such as Web-based portal applications (Za-zelenchuck & Bolind, 2003, p. 4).

The One Start study findings support a strong relationship between users’ efficiency and satisfaction. Users who perceived the system as responsive to their actions (for example, loading new screens or displaying available options) generally reported greater satisfaction than users who felt the system responded slowly. Similarly, those users able to complete their tasks in fewer attempts reported greater satisfaction than those who had to make multiple attempts.

Everything in its Place

Portal study participants frequently rationalized their satisfaction ratings (both high and low) with references to the portal interface’s organization and layout. Users commented positively in the ability to locate information in consistent screen locations, having similar units of information chunked or compartmentalized, and the ability to logically and efficiently scan information. Conversely, users commented negatively in the portal’s organization whenever new windows unexpectedly popped open, they had to scroll extensively, or they felt the combination of screen elements produced a cluttered effect. Portal designers therefore should implement, whenever possible, visual design principles for effective proximity, contrast, repetition, and alignment to optimize their interfaces’ organizational appearance. Similarly, they must guard against visual design pitfalls to avoid confronting users with unwanted and displeasing visual noise.

Feedback

Software design guidelines commonly recommend providing users with timely informative and corrective feedback. Not surprisingly, study participants frequently commented on this aspect of the OneStart portal as they explained their satisfaction ratings. Users’ comments reflected either the perceived presence or absence of adequate feedback, depending on their individual experiences. Highly satisfied users tended to perceive the feedback as being effective and adequate, whereas those who reported lower overall satisfaction with the portal criticized the system for its lack of meaningful feedback.

For Web-based portal designers, this rationale reinforces the importance of existing guidelines that call for providing users with informative feedback. This appears particularly important to allow novice users to become familiar with new systems and reach a state of competency.

Terminology

When discussing what parts of the system dissatisfied them, users also mentioned confusing terminology. For example, OneStart used such portal jargon as pages, channels, and themes. Although Web users understand the concept of a page, portals such as OneStart may confuse users by introducing individual portal pages along with actual Web pages all within the same framework.

Researchers in the usability field are well acquainted with the principles of using natural language and avoiding technical jargon. As one of his 10 usability heuristics, Nielsen recommended that interfaces demonstrate a match between the system and the real world: The system should speak the users’ language, with words, phrases, and concepts familiar to the user rather than system-oriented terms. Follow real-world conventions, making information appear in a natural and logical order. The OneStart study results support this heuristic, reminding portal designers to refrain, whenever possible, from introducing new terminology where existing terms may already suffice (Van Brakel, 2003, p. 8).

CONCLUSION

To conclude, implementing a campus portal will effectively engender a fundamental shift in the way an organisation provides services: users’ expectations for interacting with the organisation and other users (for example academic staff) are improved, for example, access to more information that is better organised. We believe that a portal should be a complementary component of the total campus’ Web design, and needs to be viewed as integral element, rather than an add-on or competing technology. A portal represents a change in the institutional philosophy with regard to the delivery of services, and is a major shift to a customer-centric design of campus-wide IT facilities.

It is clear that almost all universities will implement a portal in the next few years. Many of the leaders in the field would have already gained key competitive advantages, such as recruiting students, developing relationships with suppliers and other bodies. Those who are still undecided to implement portals will be driven by pressure from students and parents who see the benefits of portals and are choosing universities who offer them.

KEY TERMS

Collaboration Tools: Include e-mail, threaded discussions, chat, and bulletin board software that offer a whole range of ways to communicate and share information.

Horizontal Portals: Often referred to as “megaportals,” target the entire Internet community. Sites such as http://www. yahoo.com, http://www.lycos.com, and http://www.netscape.com are megaportals.

Internet Tools: Site search and navigation tools to provide users with easy access to information. Examples are calendars and planners to allow users to input and share events, as well as Web site and content builders, offering them the ability to create and have customised content being made available according to individual profiles.

User Customisation: A typical portal prompts the first time user via a series of fill-in windows to provide information about him/her. This is then stored in the portal’s database. When that user authenticates to the portal, this information determines what he/she will see on the home page immediately after login.

User Personalisation: Enables the end-user to take customisation one step further, namely to subscribe and unsubscribe to channels and alerts, set application parameters, create and edit profiles, add or remove links, and many more.

Vertical Portals: Provide access to a variety of information and services about a particular area of interest. For example, http://www.wine.com is a vertical portal. Such portals offer information and services customized for niche audiences (e.g., undergraduates, faculty).

Web Portals: Sites on the World Wide Web that typically provide personalized capabilities to their visitors.