INTRODUCTION

Education is one of the key sectors that has benefited from the continuous developments and innovations in information and communication technology (ICT). Web-based facilities now provide a medium for learning and a vehicle for information dissemination and knowledge creation (Khine, 2003). Accordingly, developments in ICTs provide opportunities for educators to expand and refine frameworks for delivering courses in innovative and interactive ways that assist students achieve learning outcomes (Kamel & Wahba, 2003). However, the adoption of ICTs has also created tensions between traditional control and directiveness in teaching and student-centred learning, which relies on flexibility, connectivity, and interactivity of technology-rich environments.

This chapter examines the introduction of Web-based technologies within a media studies course. The objective was to establish a community of learning, which provides students with a portal or entranceway into a common work area and out to networks of media related organizations. So doing, a pilot study was conducted within the Department of Communication at Texas A&M University to blend Weblog facilities with a classroom setting to enhance students’ interpersonal and content interaction, and build citizenship through participation and collaborative processes. Four key aims frame this study:

1. provide an accessible, interactive online environment in which students can participate with peers and engage with new media technologies within a learning community setting;

2. develop an instructional technology framework that enhances the learning experience and outcomes within online educative environments;

3. establish aportal or gateway for students to access media advocacy and special interest groups and enhance and diversify perspectives on global media; and

4. evaluate student-learning experiences facilitated through innovative online instructional technologies.

BACKGROUND

Early approaches to integrating ICTs into education environments emerged from conventional learning models, originating from the objectivist approach in which a reality exists and experts instruct individuals of that reality (Belanger & Slyke, 2000). However, such teacher-centric, information-based approaches failed to adequately prepare students to become independent learners. Responding to these limitations, educators embraced learner-centric approaches such as constructivism, which leant weight to the empowerment of individuals to take charge of their own learning environments. As Wilson (1996) suggests, the constructivist movement in instructional design emphasized the importance of providing meaningful, authentic activities that can help the learner to construct understandings and develop skills relevant to solving problems and not overloading them with too much information. Solis (1997) supports this position, suggesting that student-centred learning “… relies on groups of students being engaged in active exploration, construction, and learning through problem solving, rather than in passive consumption of textbook materials” (p. 393).

In spite of these favorable positions, Khine (2003) warns that creating such learning environments supported by ICTs can be intrinsically problematic. Accordingly, it is critically important that careful planning and design is employed at the early stages of instructional design to provide proper support and guidance, as well as rich resources and tools compatible to each context. When adequate consideration is given to new learning and teaching strategies that incorporate ICTs, real opportunities exist for educators to provide students with a dynamic environment to learn, to think critically, and to undertake productive discussions with their peers in supportive, constructive environments. Given the potential of such technology-rich learning environments, educators have the opportunity to make student learning more interesting and enriching, preparing them for the demands of the future workplace. Accordingly, instructional designers must consider matching the strengths of new technology (flexibility, connectivity, and interactivity) with traditional forms of education (control and directiveness) to inspire, motivate, and excite students in ways that maximize the individual’s learning potential.

Achieving these goals requires the development of individual competencies in problem solving, participation, and collaboration, and communities of learning (Kernery, 2000; Khine, 2003; Wilson & Lowry, 2000). Problem solving provides ways for students to engage with authentic episodes, providing opportunities for students and educators to examine events and reflect on solutions. One way of maximizing the benefits of problem solving is to support these through collaborative processes, which can be built around these “episodes” by focusing on the use of instructional methods to encourage students to work together as active participants on such tasks. Such efforts can be facilitated through structuring and organizing online interactions using computer-mediated communication, which provides the means to overcome limitations of time and place (Harasim, Calvert, & Groene-boer, 1997). Based on the principles of the transformative paradigm, multiple perspectives, and flexible methods, it is possible for students to adapt, to process and to filter content into their own logical frameworks, resulting in outcomes that may not be thoroughly predictable (Bento & Schuster, 2003). As Morrison and Guenther (2000) note, such collaborative environments provide a forum for students to discuss issues, engage in dialogue, and share results. However, Bento et al. (2003) also warn that one of the main challenges in Web-based education is to achieve adequate participation. They offer a four-quadrant taxonomy of learner behaviours when participating in interpersonal and content interaction–miss-ing-in-action, witness learners, social participants, and active learners—as a way of understanding this dynamic.

When building components of problem solving, participation, and collaboration around small group processes, or learning communities, it is critical that these dynamics have beneficial effects on student achievements and psychological well-being. As Khine (2003) suggests, building community imparts a common sense of purpose that assists members grow through meaningful relationships. Accordingly, learning communities can be “… characterized by associated groups of learners, sharing common values and a common understanding of purpose, acting within a context of cur-ricular and co-curricular structures and functions that link traditional disciplines and these structures” (p. 23). Rickard (2000) equates the notion of common values to that of “campus citizen,” in which students not only engage in educative endeavour but also learn networking and become “life-long members of our communities” (p. 13).

Such communities though should not be limited to just participants within narrowly defined student groups or the domain of institutional environments. ICTs also provide opportunities for students to connect to other informative communities related to their area of discipline or study via the Web. So doing, the educator can build into the instructional design gateways or portals to direct participants of small learning communities to other relevant organizations, groups, and individuals to extend campus citizenry and enhance knowledge creation. Tatnall (2005) suggests that such portals can be seen:

… as a special Internet (or intranet) site designed to act as a gateway to give access to other sites. A portal aggregates information from multiple sources and makes that information available to various users …. In other words, a portal offers centralised access to all relevant content and applications. (pp. 3-4)

In accessing Tatnall’s (2005) notion of portals, it is possible to think of these starting points in diverse ways. While no definitive categorization of the types of portals exists, Davison et al. (2003) offer a list of possible alternatives: general portals, community portals, vertical industry portals, horizontal industry portals, enterprise information portals, e-marketplace portals, personal/mobile portals, information portals, and niche portals. However, it is important to point out that these categories are not mutually exclusive, highlighting the malleable nature of these gateways for educators to blend the strengths of one with advantages of others to achieve a more effective portal design.

Even though portals are conceptually difficult to categorize and define, there exist a number of important characteristics that assist in facilitating the objectives of gateways as access points to, and aggregators of, information from multiple sources. For example, Tatnall (2005) draws from a number of scholars to present a general guideline of beneficial characteristics employed to facilitate community collaboration amongst users and the rapid sharing of relevant content and information. For example, the characteristics of access, usability, and functionality, as well as sticky web features like chat rooms, e-mail, and calendar functions, have been used to assist in maintaining user interest, attention, and participation within a site.

Within the education sector, portals offer great potential to achieve the kinds of goals laid out so far. However, portal development in these learning environments present a number of challenges for universities as they continue to grapple with a variety of business, organizational, technical, and policy questions within the framework of a larger technology architecture. For example, Katz (2002) highlights the following challenges:

• build standards to create compelling and “sticky” Web environments that establish communities rather than attract surfers;

• create portal sites that remain compelling to different members of the community within the short-term and throughout student lives;

• create the technical and organizational infrastructure to foster “cradle-to-endowment” relationships via virtual environments; and

• integrate physical and virtual sites to foster social and intellectual interactions worthy of the university’s mission.

Within this framework of challenges, the emphasis continues to return to the realization that bringing education and ICTs together strategically relies less on technology per se than on the educator’s ability to design portals that are instructionally sound (to meet learner needs), customizable and personalized (for each member of the community), meets the institutional vision and mission, and fits within the larger technology infrastructure. However, Katz (2002) argues that while the challenges are great, opportunities can be realized. With universities engaged in relationship management enterprises, the situation requires a proactive role in developing a “…belief system, a worldview, a set of approaches and technologies organized to arrange and rearrange both our front door and our rich holdings” (p. 13).

ENHANCING THE UNDERGRADUATE EXPERIENCE

Texas A&M University’s (TAMU) focus on Enhancing the Undergraduate Experience provides a series of strategies to increase and expand opportunities for students to be actively involved in learning communities. Establishing such an experience is guided by the recognition that students are involved in transitions (freshman to career) and connections (building networks).

For most students, these connections do not happen automatically. Rather, they happen because a professor or advisor intentionally creates opportunities and challenges that serve as a catalyst for such connection building. (TAMU, 2005)

To achieve and maintain such connections, TAMU implemented a three-tier model for development and implementation of foundation, cornerstone, and capstone learning communities within the university setting (see Figure 1). In developing this model for establishing learning communities, a number of recommendations were made:

1. Draw from faculty and staff knowledge to create initiatives that make existing educational opportunities even better.

2. Provide resources and incentives to develop, implement, and access learning communities; and encourage innovative pedagogies to support and reward the implementation of technology-mediated instruction, use of peer instructions and collaborative learning.

3. Provide a clearinghouse so the benefits from experience and expertise can be utilized in future design and implementation of learning communities. (TAMU, 2005)

With this framework in mind, a Weblog was integrated into the COMM 458 Global Media course using a generic blogger.com template as part of pilot study funded by a $3,000 TAMU Summer Institute for Instructional Technology Innovation Grant. The template included an archive (of posts and comments), calendar function, a database of user information including e-mail links to registered members, email notification facility, and links to other relevant websites. In providing 22 students access to Weblog facilities, the study set out to establish a model of content production and platform interoperability for inspiring innovative and creative appropriation of Web-based facilities by TAMU students and faculty. Accordingly, the Weblog was strategically integrated into the course to achieve the following outcomes:

• facilitate community building and understandings of social networking and citizenship at local, national and international levels;

• provide a platform for students to evaluate, communicate and critique current issues and problems within informal and engaging online environments;

Figure 1. Learning community model

|

Time Line |

Courses |

Content |

Outcomes |

|

Freshman |

Foundation |

Introduce competencies |

Critically analyze, Personal integrity, Contribute to society, Communication |

|

Core Curriculum Courses |

|||

|

Sophomore, Junior, or both |

Cornerstone |

Reinforce and integrate competencies in the discipline |

Critically analyse, Master depth of knowledge, Communication |

|

Senior |

Capstone |

Emphasize, synthesize and apply competencies in the discipline |

Critically analyse, Master depth of knowledge, Personal integrity, Communication, Contribute to society |

|

Career or Graduate School |

|

||

• improve content, information and knowledge management within the course structure;

• improve teaching and learning through understanding the dynamic between participation and collaborative processes within a blended educative environment; and

• develop alternative pedagogical and technological strategies to support and encourage each student to become an independent learner.

All students were invited to be members of the Weblog community by e-mail, which contained a hyperlink that directed them to blogger.com’s registration site. There, students selected a user name and password, which brought them into the course Weblog site (see Figure 2). Once in the site, members could interact with each other by posting summaries of readings (including discussion points and questions), comment on posts in which students raised issues and problems (moderated by the course instructor), and source stories and information from national and international news services (e.g., CNN, BBC, or Aljazeera). Users were also given the task of building a database of relevant links to outside media organizations and advocacy groups to assist each other in answering problems and issues posed within online and classroom discussions. All students were assigned administration rights to the Weblog to instil a sense of ownership among members.

FUTURE TRENDS

Participation within the Global Media course (online and classroom) was measured in several ways, including the number of entries (posts and comments), user log-ins, survey, interviews, and observations. Overall, students and instructor made a total of 303 entries (72 posts and 231 comments) over the 10-week period from September to November of the 2005 Fall Semester. On average, there were 3.25 comments per post. However, included in this number were 108 comments (81% response rate) by students to a series of six quizzes (which accounted for 15% of the course’s total grade) implemented throughout the semester to test students’ general knowledge of key theories and concepts. When the quiz comments were excluded and the figure re-calculated, the average number of comments per post significantly decreased to 1.70. These figures would suggest a relatively poor level of participation in online interactions. However, these figures do not reveal the complexity of the online-classroom dynamic in catering for different learner preferences. Another way of assessing student participation is to categorize their behavior into types of interactions through observing participation in both settings.

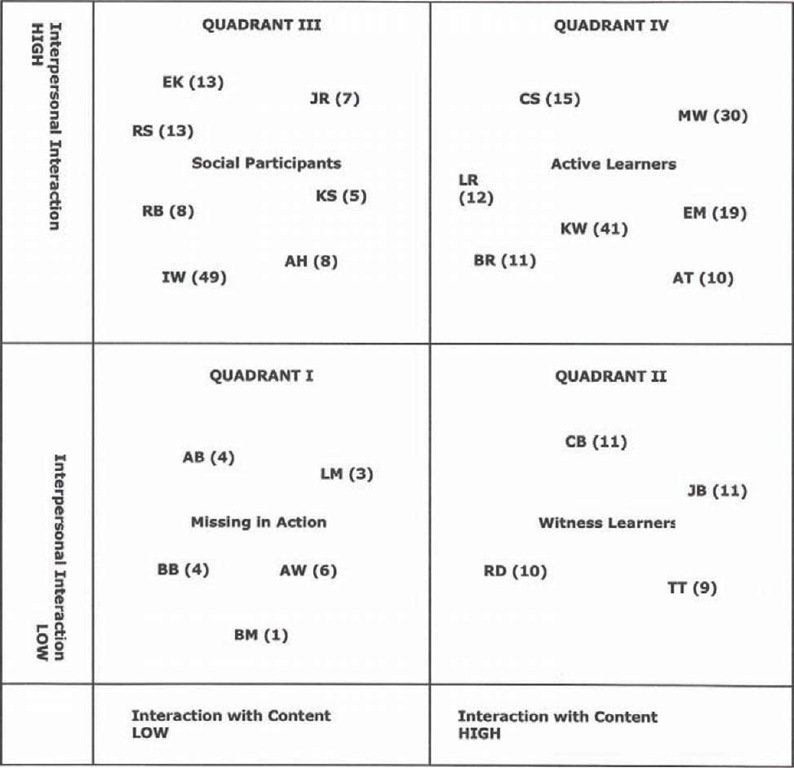

Drawing from Bento et al. (2003) four-quadrant taxonomy, it is possible to map the types of behaviors these learners engaged in as part of the participatory and interactivity components of the Global Media course (see Figure 3). Quadrants I and II share the characteristics of low interpersonal interaction. However, whereas Quadrant I students do not care about course content and their peers, “witness learners” are actively engaged with the course materials and discussion (high content interaction), log in frequently and do all the readings but do not actively contribute to course discourse (low interpersonal interaction). On the other hand, Quadrants III and IV share the characteristic of high interpersonal interaction. Students in Quadrant III (high interpersonal interaction, low content interaction) thrive on the social aspects of education, demonstrating characteristics of great conversationalists, with high communication and interpersonal skills. Such students, though, engage in social interaction most often at the expense of reflection and thoughtful consideration of course content. Quadrant IV represents what educators define as “good participation,” with high content interaction and interpersonal interaction. Their contributions in discussions are substantive and frequent. Accordingly, Bento et al. (2003) argue that these students contribute not only to the problem-solving task but also to building and sustaining relationships in the learning community.

Figure 2. COMM458 Global Media Weblog site

Given the findings of the study, the Weblog added value to the learning community by providing students with access into a common area to connect and interact with one another and as a gateway out to sources of information beyond the confines of the institutional environment. Through student-established links to media organizations and advocacy groups, members connected to important and divergent understandings and knowledge of the role of media in a global context. One student comment encapsulates the general feeling of course participants toward the Weblog facilities:

Figure 3. Taxonomy of COMM 458 course student behavior relating to content and interpersonal interaction

… Even if all students had equal enthusiasm to participate in class discussion, class time limits everyone from making significant contributions and feeling part of learning. Blogs provide a place for sharing related material [discussion and provision of links to outside sources] that the classroom setting does not, and a way to question or comment on material we have already covered. In general, blogging let’s students engage with each other in a way different from class. By allowing discussions to continue and expand, it helps students who struggle with the material or who are afraid to ask questions in class. It certainly helped me to learn much more than just reading textbook information.

In spite of these positive responses, the chronologically organized Weblog structure offered insufficient flexibility and functionality to increase online participation. Given the findings, the study recommends re-designing the Web-based learning environment using software, innovative interfaces, and workflows. So doing, there is a need to:

1. Develop a technology interface that acts as an en-tranceway into a series of linked, embedded pages so (a) information storage and retrieval; (b) discussion and commentary; (c) communication; and (d) project facilitation can be purposefully compartmentalize to improve technology, content, interpersonal and intellectual interaction.

2. Integrate chat room facilities into the portal design to create more compelling, sticky Web-environments for participants to interact in real-time with peers and instructor.

3. Introduce more comprehensive monitoring facilities to track technology, content, interpersonal and intellectual interaction, providing instructors with timely diagnostic metrics to enhance decision making during course implementation.

4. Develop more strategic collaborative, problem-solving tasks and exercises to increase participation and improve content, interpersonal, and intellectual interaction.

CONCLUSION

This article presented pilot study findings on using weblog facilities to increase participation and improve interaction in Web-based learning communities. The study revealed a number of aspects to assist educators in providing more structured and comprehensive online learning environments. The most important of these are people-related functions such as creating strategically-focused collaborative learning environments and improving the quality and quantity of, and accessibility to, course metrics to help educators make informed, timely decisions in online instructional environments. Accordingly, it is anticipated that the recommended strategies will improve participation and interactivity and contribute to more productive, supportive learning communities.

KEY TERMS

Constructivism: Learning as interpretive, recursive, building processes by active learners interacting with physical and social worlds.

Information and Communication Technology (ICT): Refers to an emerging class of technologies—telephony, cable, satellite, and digital technologies such as computers, information networks, and software—that act as the building blocks of the networked world.

Learning Communities: Characterized as associated groups of learners, sharing common values, and a common understanding of purpose.

Portal: Considered an all-in-one Web site that acts as a centralized entranceway to all relevant content and applications on the Web.

“Sticky”: Web Features include chat rooms, e-mail links, and calendar functions.

Student-Centred Learning: Focuses on the needs of the students rather than on teachers and administrators, resulting in implications for the design of curriculum, course content, and interactivity of courses.

Weblog: A personal dated log format that is updated on a frequent basis with new information written by the site owner, gleaned from Web site sources, or contributed to by approved users.