KEY CONCEPTS:

Upon completion of this topic, it is expected that the reader will understand these following concepts:

• Paramedic wellness defined as more than absence of disease

• The body’s responses to both positive and negative stresses

• Stress management techniques for managing acute stress and chronic stress

• Safety tips and stress management prevention strategies

Case study:

"I can’t believe that I pulled my back on that last call," said the young Paramedic. "Now what am I supposed to do? We’re expecting our first baby and I’ve got the house payment and car payment. I can’t be out of work and I need the overtime!"

OVERVIEW

The health and wellness of the Paramedic goes beyond simply avoiding illness.

It involves the social, spiritual, intellectual, emotional, and physical well-being as a part of a well-balanced lifestyle. The Paramedic encounters stress each day. This stress can have a harmful physiological effect on the body. It is important for the Paramedic to have built-in mechanisms for stress management and be familiar with the methods of crisis intervention to help prevent stress related illness.

The Paramedic has many responsibilities, but perhaps the most important is personal safety. Focusing on the Paramedic’s response to emergencies and scene hazards, awareness is what can keep the Paramedic, his team, and the public safe. Safety is more than body substance isolation.

Wellness

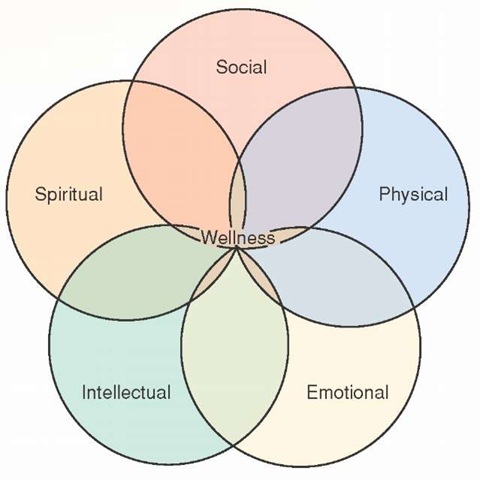

The concept of wellness could be thought of as merely the absence of illness. However, this simplistic approach fails to take into account the complexity of human existence. Wellness is a multidimensional concept which includes all aspects of a person—social, spiritual, intellectual, and emotional—as well as physical well-being (Figure 3-1).

One definition of wellness, advanced by DePaul University, is that wellness is an active process of becoming aware of, and making choices toward, a more successful existence. This definition, intrinsically, implies that wellness is more than an absence of illness, which could be thought of as the lowest level of wellness. Paramedics who are aware of the practice of wellness are more likely to not experience illness and to lead more productive lives.

Figure 3-1 The interconnectedness of wellness.

Benefits of Wellness

The benefits of wellness include a heightened sense of purpose, an inner tranquility, as well as a physical being capable of greater feats. Physical health is the most outward sign of wellness. Physically, the healthy body is more resistant to injury (such as back injuries), as well as to illness. The body, as a machine, functions better with a lower resting heart rate and blood pressure, more respiratory reserve, and generally has a better cardiovascular capacity when it is healthy. Risk factors for all of the major diseases—cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer—are reduced in healthy people.

Methods Used to Achieve Wellness Nutrition

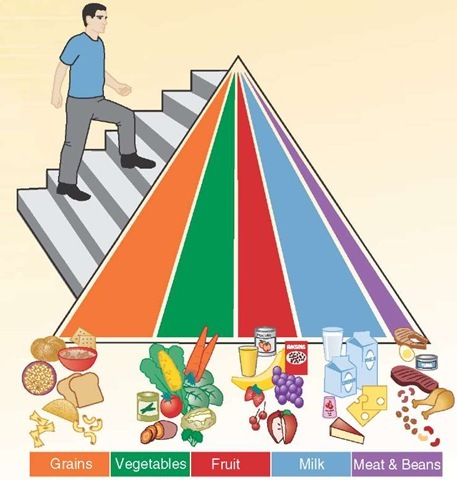

The components of physical health include a proper diet, one that provides the necessary nutrients, in the quantities sufficient for life. A balanced intake of carbohydrates for quick energy, fats and proteins for body maintenance, as well as essential vitamins and minerals, can help the body maintain optimal functionality. These nutrients can be obtained from the major food groups illustrated in the Department of Agriculture’s Food Pyramid (Figure 3-2). Foods, taken in the quantities indicated, can sustain a body and provide it with the materials and resources it needs to withstand the stresses encountered in emergency services.

Food should always be eaten in moderation, with attention paid to the type of foods being eaten. Excess amounts of fatty foods, for example, or excessive intake can lead to obesity. Obesity is a growing health crisis, second only to cigarette smoking as the leading cause of preventable death.1,2 Obesity can lead to a host of associated complications including diabetes and cardiovascular disease.3-6

Medically speaking, a person is obese when his body mass index is 30 or greater.7 A common layperson definition of morbid obesity is 100 pounds over ideal weight. Over 60% of American men are obese by definition and therefore have an increased chance of illness, injury, and premature death.

Figure 3-2 United States Department of Agriculture’s Food Pyramid with a new emphasis on exercise.

STREET SMART

Specialized bariatric equipment is available to help transport patients with obesity. The Paramedic should know how to obtain this equipment and use it to prevent personal injury.

Exercise

Exercise is also essential to physical health. A combination of aerobic exercise (e.g., walking or jogging), as well as strength training is considered optimal for maintaining health. Whether using free-weights (isometric) or resistance exercises (isotonic), strength training can lead to increased muscle strength and flexibility (Figure 3-3). This in turn can help reduce the incidence or the severity of on-the-job injuries, particularly back injuries.

PROFESSIONAL PARAMEDIC

Some Paramedic employers contract with chiropractors, personal trainers, or health educators with a specialty in injury prevention to conduct assessments and teaching sessions in an effort to reduce back injuries.

Figure 3-3 Physical fitness is essential to longevity in EMS.

Stress

Stress is a function of daily living, a result of the interaction between the person and the environment. During the course of a day, the human body is constantly being bombarded by stimuli. The body reacts to this stimuli accordingly. The amount of stimulation results in a certain level of stress in the body. If the stress is manageable (i.e., tolerable within the limits of a person’s physical, psychological, emotional/ spiritual, and intellectual capacity to respond to the stimuli), then it is a positive form of stress or eustress. Eustress can lead to improved health as well as a sense of fulfillment or accomplishment.

Alternatively, overwhelming stimuli can lead to unhealthy stress, which in turn can have a negative impact on the person. This is called distress. Distress is the result of the body’s maladaptive reaction to stress. The stimulus causes the body to react in a self-protective manner. This "survival instinct," awareness of and the ability to respond to one’s surroundings, is immediate and uncontrollable.

When distress occurs, the body undergoes a reaction controlled by the autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system can affect organ function throughout the body. Walter Cannon coined the term "fight or flight" to describe the generally adaptive response of the autonomic nervous system to stress. "Fight or flight" describes the body’s instinctive response to a potential life threat. This primitive stress response may have been critical to the survival of primeval man, but can be unhealthy today.

Modern man faces a host of new behavioral and emotional stressors beyond the mere physiologic stressors faced by early man. Modern stressors include psychosocial pressures from family, coworkers complaints, and supervisors’ demands. In addition, intellectual pressures to perform to perhaps unrealistic expectations, as well as new physiological stressors that include noise pollution from sirens wailing, can lead to distress. Distress can be caused by any stimulus that creates a maladaptive response from the autonomic nervous system.

Hans Selye, an endocrinologist, observing the impact of stress upon physiology, advanced his theory of the "general adaptation syndrome." In his theory he suggested that all human experience creates stress, but it is how the person responds to that stress that determines if it is eustress or distress.8-10 Selye believed that the power of the body to resist distress, over a prolonged period of time, was limited and that the body would eventually become exhausted and typically manifest in mental or physical illness.

Symptoms of Stress

The manifestations of a Paramedic’s pending exhaustion from stress can be divided into psychological, cognitive, behavioral, and physiological signs and symptoms.

For some people, the psychological signs ofdistress include an unreasonable irritability at seemingly minor annoyances, uncharacteristic angry outbursts, open or covert hostility, and a general restlessness. For other people, distress is manifested by depression, withdrawal, self-deprecation, as well as reduced self-esteem. The Paramedic may also manifest stress by having uncharacteristic bouts of forgetfulness, reduced creativity, shortened attention span, and disorganized thought.

The person under extreme stress may demonstrate uncharacteristic changes in behavior such as increased smoking, aggressive behavior (e.g., road rage), increased alcohol or drug use, over-eating, and a general carelessness about and withdrawal from activities of daily living. All of these may be signs of impending stress-induced crisis.

Walter Cannon referred to the symptoms of stress as a "fight or flight syndrome" and all of the manifestations of stress, system by system, are all attributable to a heightened autonomic nervous system state. The autonomic nervous system’s function can be roughly divided into two portions. The first portion, the parasympathetic nervous system, is responsible for the involuntary vegetative functions including digestion, heart rate, and the like, largely controlled by the vagus nerve. These functions are summarized as "feed and breed."

The other autonomic nervous system responses are the result of the sympathetic nervous system. Normally the sympathetic nervous system includes those emergency responses that are at "stand-by," ready to provide the person with the ability to flee (flight) or fight. Under normal conditions, the parasympathetic nervous system takes dominance, through vagal tone, and maintains homeostasis. However, under emergency conditions in which there is sufficient stimulus, the epinephrine-based sympathetic nervous system assumes more dominant control of the organs’ functions.

The sympathetic nervous system is greatly influenced by the brain’s cognition, that ability to comprehend stimulus, and thought, the ability to comprehend a stimulus’s meaning. When repeatedly overstimulated, perhaps by constant bombardment by stress-inducing stimuli, the body begins to show the fatigue, a prelude to illness in many cases, in a condition called strain.

The chief neurotransmitter in the sympathetic nervous system is epinephrine. Epinephrine has organ-specific effects that alter that organ’s function. For example, epinephrine attaches to beta-receptors in the heart to make it contract more forcefully (inotropy) and more quickly (chronotrophy). Simultaneously, epinephrine also attaches to alpha-receptors in the peripheral vasculature, leading to increased peripheral vascular resistance (PVR).

The stimulation of both receptors, alpha and beta, by epi-nephrine released during a stimulus response causes the heart to beat faster and harder against a greater resistance (PVR). The heart’s increased workload leads to cardiovascular complications if the stress is prolonged.

Stress can also cause abnormal contraction of skeletal muscles, contractions beyond their functional needs, leading to muscle spasms, spinal column misalignment and resultant backache, contraction of facial muscles leading to headache, jaw clenching, nocturnal teeth-grinding (brux-ism), and neck pain. Internally, the immune system, set on high alert for potential bacterial invasion, eventually fatigues. T-lymphocyte counts drop, resulting in immunosuppression and, paradoxically, more infections. The signs and symptoms of overstress, or distress, include persistent tachycardia, palpitations, hypertension, chest pressure, and chronic pain.

Physical disorders associated with chronic high stress include, from head to toe, migraine and tension headaches, cardiovascular disorders, respiratory disease, ulcers, and colitis, as well as hypertension and cancer.

Emotional and behavioral disorders are also associated with stress. These include anxiety, with associated panic attacks, depression, alcoholism, and conduct disorders. These emotions, behaviors, and somatic complaints should alert fellow Paramedics that the person is under stress and may or may not be coping well emotionally.13

The human psyche is not immune to the effects of chronic stress either. The psychological defense mechanisms against stress include projection, denial, and conversion, among many others. When the individual’s coping mechanisms fail to provide the relief needed, the individual may resort to mal-adaptative coping mechanisms. Examples of these maladapta-tive coping mechanisms include substance abuse, alcoholism, smoking, and the use of other addictive substances.

The Crisis Process

A person is in crisis when he has experienced a threatening event but no longer has the capacity to respond, due to mental and/or physical exhaustion. The crisis process is somewhat analogous to the transition from compensated to decompen-sated shock. Anxiety, panic, and, in some cases, terror sets in and the patient may become profoundly depressed or start to manifest frank psychiatric symptoms.

Like the shock syndrome, the crisis process is reversible, provided a crisis intervention is provided in time. The goals of crisis intervention start with stopping the acute process. Depending on the situation, this may be accomplished simply by removing the person from the source of the stimulus. Once removed, the downward spiral of emotions must be stopped and the person’s thoughts and/or feelings can stabilize. In other cases it will take psychotropic medications and/or acute crisis intervention to stop the crisis. With the acute symptoms managed, the goal of crisis management is to return the person back to independent functioning.

One example of a crisis intervention approach used for emergency services personnel is the SAFE-R model (Table 3-1). The letters in the SAFE-R model each stand for a step in the process. Stimulation reduction (S) is the first goal of crisis intervention using the SAFE-R model. Next, the facilitator would then acknowledge (A) the crisis and, using carefully chosen probing questions, facilitate (F) an understanding of the situation.

After gaining the person’s attention, using empathy and therapeutic communications, the facilitator would explain (E) the basic concepts of stress. The universality of stress would be emphasized and the facilitator would offer some plans for coping with the current situation. Finally, the facilitator would discuss a plan to return or restore (R) the person back to independent function.

While the SAFE-R technique appears easy, as the saying goes, the devil lies in the details. Crisis interventions are best left to personnel trained in critical incident stress management.

Stress Management

Stress management is a process of coping with chronic stress in an effort to recover from its effects. In some instances, the individual can take action to eliminate the source of the stress. This activity would constitute stress reduction. A job change or even divorce can be examples of stress reduction. If the source of the stress cannot be eliminated, then some action must be taken to reframe the brain’s interpretation of the stimulus so that it is non-threatening. This technique, called cognitive restructuring, provides hope for recovery for some people with fatigue, strain, or stress.

Table 3-1 SAFE-R Model

|

S |

Stimulation reduction |

|

A |

Acknowledge the crisis |

|

F |

Facilitate |

|

E |

Explain |

|

R |

Return or restore |

To understand the benefits of stress management, Paramedics need to first learn to recognize the early warning signs of stress, both immediate and long-term. Examples of the effects of long-term stress include recurrent headaches and unremitting fatigue. Part of managing stress is recognizing events that trigger stress and attempt to either eliminate them or respond to them differently.

There are several effective models for stress management, both short-term and long-term. For short-term stress some EMS responders use controlled breathing or isotonic exercise. Long-term methods of stress management are discussed shortly. In every case, Paramedics need to become aware of their warning signs of impending stress and plan how they are going to respond to those stressors.

While stress management is focused on the individual, in this case the Paramedic, there are organizational benefits to stress management training. In a cost-benefit analysis, the loss of time in stress management training is outweighed by loss in sick leave, worker’s compensation, associated medical costs, and employee turnover. Paramedics who learn how to manage their stress tend to have increased morale, decreased conflict with fellow workers and supervisors, reduced errors, and enhanced performance while on-the-job.

Paramedics can learn a number of stress management techniques that will help mitigate the long-term effects of stress.14-17 The majority of these techniques can be done quietly, on-the-job, and without additional equipment. One technique, autogenic training, stems from the practice of autohypnosis first advanced by Vogt in 1900. A form of "self-regulation" akin to biofeedback, autogenic training was developed in 1932 by Johannes Schultz as a means to train the autonomic nervous system. Other stress management techniques that emphasize the power of the mind-body connection include progressive muscle relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing. Some Paramedics have been trained in the use of mental imaging, which is useful for immediate stress relief, as well as meditation. Meditation has long been known as a technique for stress reduction.