Humor

"Although pixilation has been explored since Norman McLaren’s work in the 1950s, it had tended to be used largely for slapstick effect. Our initial interests were in trying to use the technique in a more subtle and expressively dramatic way.

"The intention was to make a film that looked like live action but [moved] like an animation film. When successful, the technique creates a distorted realism that can very effectively be used to accentuate or exaggerate a character’s personality and presence. It was that possibility of manipulating the dramatic performance of a character that led to the use of pixilation techniques in the Thumb project"

As Dave Borthwick points out, many pixilated films have leaned into humor and slapstick, primarily because the fast and energetic movement of pixilation tends to strike the "funny bone" Yet, this technique of animating people also lends itself to more serious subject matter. The more control of expression and movement, the more serious the effect can be. As Lindsay Berkebile points out, using holds with as little movement as possible in a human animated subject can emote a sense of quiet desperation or an inner energy and conflict that may reveal another layer of interpretation in an animated performance. The key is in the performance, expression, and overall movement.

In Jan Kounen’s Gisele Kerozene and in Norman McLaren’s Neighbours, the action is so broad and absurd that one cannot help but laugh. In Neighbours, when one of the battling men, played by Grant Monroe, hits the other neighbor’s wife with a picket fence post, throws her baby to the ground, and kicks the baby off screen, we cannot help but laugh despite the dark humor involved. It is so tragic that it actually becomes comedic, and the fast paced action of the pixilation feeds the humor. As Terry Gilliam states, "…serious ideas can often be communicated very powerfully with humour"

A few techniques can be used to help smooth out the action of a performance, allowing for more serious interpretations. It appears that the more time spent between frames adjusting people leads to the potential for more quirky and misregistered movement. This can be very funny looking. But, if the movement of a character is smoother, then the effect can lean more toward serious interpretation. Expression and performance play a key role, but we are concentrating strictly on movement. So, if an actor being shot frame by frame moves slowly and constantly and the camera operator continuously shoots frames, capturing the in-betweens of action at a more even pace, the action will be smoother, mimicking live-action movement. A minimum of time should be spent between shot frames. If the person being shot is moving constantly in a particular direction, then he/she will be better registered in placement from frame to frame than spending minutes between frames adjusting position and losing that registration.

Surprise is always an effective way to conjure up a good laugh. Pixilation allows a filmmaker the ability to change the subject matter or position of the subject within the frame for each shot. This erratic movement combined with unexpected action and subject placement within a frame is fun and surprising. That elicits humor. Quick movement similar to the animation in cartoons, like the work of Warner Brothers director Chuck Jones, can raise a laugh. Treating human subjects like cartoons that whip across a frame, do the impossible (like dancing across a dance floor on their fingers, slamming into walls with no consequences, and other humanly impossible feats) make us laugh and think of these human subjects as unreal. This quick stylized movement is what Dave Borthwick was referring to when he mentioned that a lot of pixilation was relegated to the slapstick world.

Shooting on Twos, Fours, and More

Often pixilation filmmakers mix together smooth and quirky misregistered movement. This adds an interesting dynamic movement to a film. We just explored constant shooting of the single-frame camera, but the mixture of live-action photography and pixilation can be very effective to achieve this dynamic. A great example of the mixture of frame rates is Norman McLaren and Claude Jutra’s 1957 animated short, A Chairy Tale. McLaren and Jutra would often shoot at half normal live-action speed (12 frames per second) to speed up the action and blend that footage with the more time-consuming frame-to-frame manipulations.

FIG 3.7 Still from A Chairy Tale, Norman McLaren and Claude Jutra

Another successful practitioner of the pixilation and live-action mix is Jan Svankmajer. It is blended so well that the viewer easily falls into the magical space that is created with these practical and photographic effects. In the 1994 film Faust, Svankmajer cuts back and forth between the live action, pixilation, and clay models of Mephisto.

Jan Kounen did the same thing in Gisele Kerozene and claims, "I’m no more thinking of stop motion as a genre, but only as a technique; even in Gisele Kerozene, there is 20% of real stop motion the rest is shooting continuously at 2 frames a second, or 6 frames"

FIG 3.8 The clay head of Mephisto from Faust, Jan Svankmajer,

Both McLaren and Kounen were shooting with movie film cameras that allowed them to vary the shooting frame rate. The present day digital still cameras now have the capability to shoot live-action movies and the newer models shoot in high definition. They are starting to include features like variable frame rates; for example, the Nikon D-90 shoots 1 to 4 frames per second and the Canon 7D can shoot 24, 30, and 60 frames per second. Many digital video cameras have this various frame rate feature available, because they were made to shoot live-action video. The digital still cameras are not far behind. Please refer to the associated website to see the latest in camera technologies.

For animators that have no access to this higher-end equipment, using the continuous shooting technique helps vary the look of pixilated film. When you shoot "pure" stop motion or heavy manipulation of the subject matter between frames, you need to consider how many pictures or frames you want to use for every increment of subject movement. Since moving human subjects is physically challenging, it is best to reduce the amount of work demanded of them. I often shoot my human subjects at a rate of 15 frames per second and play back the footage at 15 frames per second. Or, you can just shoot two pictures for every movement of the human subject and play it back at 30 frames per second. This technique, known as shooting on twos, has the same effect as shooting at 15 frames per second (fps) with a playback of 15 fps. Since NTSC (the National Television System Committee) video is 30 frames per second, that is the rate I like to use. This is most common in the Americas and parts of East Asia. In film, the projected playback rate is 24 fps, so many animators shoot two pictures per movement, played back at 24 fps. But, if this film is transferred to video, then there is an interpolation made to stretch those 24 frames into 30 fps by averaging out two frames every five frames of footage. This works well but can be somewhat problematic if you are creating special effects frame by frame in postproduction, where every frame needs to be a clean distinctive image. In this case, images are worked on in the effects area at 24 fps then stretched to 30 fps after the effects work is done.

Variations on Pixilation

Although the animation or pixilation of people is quite popular, so is the combination of people and two-dimensional graphic elements, the animation of light, and the animation of everyday objects. Mixing people frame by frame with drawn animation, graphics, and objects elicits an infinite variation of this genre. The important element that distinguishes this approach is that combining these elements occurs directly in front of the camera and not in a postproduction process. One example of this approach is by filmmaker Jordan Greenhalgh, an independent filmmaker in New York. Jordan made a film, Process Enacted, in which he shot his human subject frame by frame with a Polaroid camera then animated the Polaroid photographic prints on a tabletop.

FIG 3.9 Images of multiple Polaroids for Process Enacted, Jordan Greenhalgh,

This is a time-consuming, difficult process, because it requires twice the amount of animation, once for the human figure and once for the animation of the Polaroid photographs, but the results are fascinating. In this kind of approach, spontaneity of production can be risky, so planning ahead reduces that risk. Jordan states:

"I test shoot every idea. I have to work out the technical kinks. I also storyboard and make animatics to get a feeling for the film as a whole."

A contemporary, Italian born, graffiti artist/animator, Blu has made several films that feature paintings on buildings that animate across an entire neighborhood or urban environment. His animation is often shot in outdoor environments, where the natural movement of light helps keep his frame active and fluctuating in exposure. He then adds constant movement to his camera in an erratic fashion that infuses an energy and freshness to the image. There is an aesthetic choice to this approach as well as a practical advantage. By moving the camera constantly, the viewer accepts the active camera and consistent jittery motion, which helps mask any unplanned exposure, lighting, or camera placement changes. These changes may occur naturally, due to weather, time, or unforeseen obstacles. This technique, like most stop motion, is difficult and time consuming, and single shots may take days or weeks to complete. He can stop in the middle of a shot at the end of one day and start up again several days later, yet the shift in the image does not stand out. It is impossible to control external conditions for any extended period of time outdoors, so Blu’s aesthetic and practical solution works very well. Since the overall frame is so active, Blu creates strong striking graphic images, like in his 2008 film Muto and his 2010 film Big Bang Big Boom.The eye is drawn to the constant morphing and moving image and is not distracted by the highly active overall frame. This contrast and focus of the eye is highly effective.

In both films, Blu moves his images from graphic flat painted images to threedimensional forms that may carry some of the painted graphic elements on them as they move through the frame. Occasionally, Blu appears in and out of the frame, revealing some of the process of making the actual film.

FIG 3.10 A series of three shots from Muto showing the movement in composition from one frame to the next.

FIG 3.11 Shots from Big Bang Big Boom demonstrating the use of two-dimensional and three-dimensional elements shot frame by frame.

Light is an element that many contemporary artists are starting to rediscover.

Light generally plays a big role in photographic frame-by-frame animation because it gives form to objects and sets atmosphere. Pixilation filmmakers create films both indoors and outdoors with controlled and "wild" lighting, lighting that occurs naturally. The sun is the largest light that we utilize, but human generated lights both in the studio and out in the streets have great potential to be exploited. Painting with light, frame by frame, has begun to expand with today’s technology. By using LED lights or even bright flashlights in a dark environment, you can create a light painting. Like the other techniques discussed, you must use a dslr camera that has all manual controls on a tripod. By setting the shutter speed to a long exposure (at least 2 seconds and potentially longer), you can draw streaking light images frame to frame.

FIG 3.12 Tools required to light paint—camera, tripod, lights (LED, etc.)-and colored gels.

The light(s) must face the camera lens as you draw an outline or image. Since the room is dark, the light painter should wear dark clothes and may disappear from the final image all together. It is also helpful for the light painters to move their position frame to frame to help hide their presence. The light, which is bright and moving, leaves a strong streak of color (if you use colored lights) that creates a drawn image on the frame. Some artists create images freehand for every frame. It is important to know the shape being drawn and to be able to repeat it or potentially change that image frame to frame like any animation. You can have a person or cutout of the shape you want to draw as a guide when you light paint, if you need that kind of consistency.

FIG 3.13 Guides for light painting.

New approaches to light painting include using iPads as the source of light.

By predetermining certain shapes and colors, the light painters can move in the dark with their iPads in hand. The iPad image changes frame to frame, and the movement of the painter holding the iPad and a long exposure allows words and more distinctive shapes to be extruded exposure by exposure.

FIG 3.14 an ipad held in the dark to form a distinctive shape.

The final area of pixilation I want to cover is what I call object animation.

This is very close to model animation and is treated in a similar fashion. The main difference is that the objects have little or no manipulation performed on them. In puppet or model animation, sculpting, armature fabrication, molding, painting, and a whole series of processes are involved before that model is put in front of the camera. In object animation, usually, very little is done to the object. The animation of an object, how it is moved, is the way that expression and storytelling is achieved with this technique.

One of the most successful contemporary artists in this area is an American animator who calls himself PES. Although not trained in animation, PES worked in the advertising industry in short subject filmmaking (commercials). Some might consider PES a three-dimensional collage artist. In his first successful film, mentioned earlier in the topic, PES animated real chairs on the roof of a New York City apartment building. This film, Roof Sex, has a strong sense of art direction in color and composition and the chairs, which bare no human features, are moved in a way that mimics humans consummating. Understanding the effects of movement through testing and reference film allows an animator to reproduce a particular action that may not normally be associated with that object. As humans, we recognize certain actions associated with our species, because we understand ourselves (mostly). Once that motion is transposed onto another object, we identify and find interest and humor. PES has a simple trick that he uses on his website and in his 2009 film, Western Spaghetti. He mimics a flame, on a stove or in a fireplace on top of pretzels (that look like logs) using several different size candy corns and replacing them in front of the camera every two frames. It is so simple but so effective. This technique, which is known as replacement animation, calls for the substitution of one object for another similar but different object. The changing objects create an animated effect. This is one way to achieve squash and stretch in object animation. Replacement animation is one of the cornerstones of all stop-motion techniques. People can be substituted for people, objects can be substituted for other similar objects, and the effect can be magical, as in the PES candy corn flames.

FIG 3.15 Several different sizes of candy corn are used as replacement models, imitating a flame.

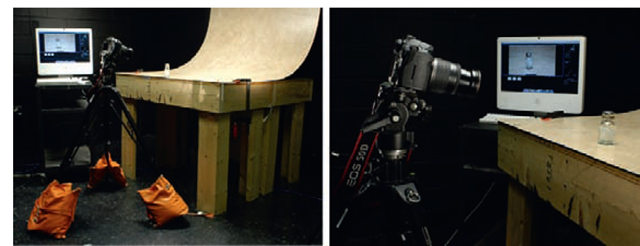

One simple exercise that anyone can try involves taking any object, like a saltshaker, and moving it around a table in front of a camera, frame by frame. This requires a digital still camera or a digital video camera that is controlled or hooked into a capture software program, like Dragon Stop Motion or Framethief. Dragon works well with the digital still cameras and standard definition digital video cameras work well with Framethief. Mount your camera on a tripod and lock it down with tape or sand bags. Make sure the tripod is on a hard flat surface like a concrete floor. Do not mount your tripod on a rug because the "give" in the rug could move your camera. Put a simple light on your saltshaker and start moving it around, bit by bit, frame by frame. Shoot two pictures for every move ("on twos"). Capture about 3 seconds of this. Now, find a piece of live-action film of a person who is very nervous or any other kind of dramatic emotional state. This reference film should be a Quicktime movie, so you can look at it frame by frame. Notice and analyze how the person is moving frame to frame. Once you understand the action on a single frame basis, transpose this movement onto that saltshaker. Try to be as true to the reference film as possible, and even try exaggerating that movement. If you do this successfully, then you will understand the power of controlled animated movement in everyday objects.

If you want to add another layer to this experiment, then try to find a saltshaker that comes in three different sizes. You can substitute the salt shakers, one for another, to get a breathing effect, expanding and contracting.

FIG 3.16 Setup for the saltshaker experiment.