Abbett, Leon (b. Oct. 8, 1836; d. Dec. 4, 1894). Governor, politician, lawyer, and jurist. Leon Abbett was one of the ablest and most intriguing men ever to serve as governor of New Jersey. Although he was both a machine boss and a spoils politician, he was also a reform-minded lawmaker of considerable importance.

Abbett was born in Philadelphia, the son of Ezekiel Abbett, a hatter, and Sarah Howell. He graduated Central High School in 1853, studied law, and became an attorney in 1857. On the eve of the Civil War, he moved to New York, where he practiced law and entered into a partnership with William Fuller.

In 1862, Abbett married Mary Briggs of Philadelphia and set up housekeeping in Hoboken. Two years later, Abbett entered politics and won a seat in the state assembly. Relying on his traditional base of Democratic support in Hudson County, he steadily moved up both the party ranks and civic positions; he served as Speaker of the General Assembly (1869-1870) and president of the State Senate (1877). In 1883 he was elected governor of his adopted state. Although his career on the face of it followed a logical progression, he had long defied the ruling elite, and, even within the Democratic party, he stood against the wind.

Affectionately known as the "Great Commoner,” Abbett appealed primarily to the deprived urban lower classes and the marginally deprived agricultural yeomanry. He served two terms as governor: first from 1884 to 1887, and again from 1890 to 1893. By capitalizing upon labor unrest, ethnic conflict, and a generation of agrarian discontent, he demonstrated a capacity for leadership that enabled him to arouse enthusiasm among constituencies demoralized by the domination of big business and concentrated wealth. An urban populist reared in the Jacksonian spoils tradition, he voiced the sentiments of the common man beset by the intransigent forces of unrestrained capitalism and special privilege.

Undoubtedly, the boldest act of Abbett’s career was his battle to tax the railroads. This audacious venture was fraught with risk. Although he won the protracted battle, he paid a heavy price. The powerful railroads used their political clout to defeat him for the U.S. Senate in 1887. Upon his reelection as governor in 1889, he pushed through a ballot reform law designed to reduce vote fraud.

To right the wrongs of oppressed labor was Abbett’s passion. He initiated a series of laws that improved conditions of industrial employment. He established standards of occupational health and safety, maximum hours, and wage payment in cash rather than scrip. He abolished convict labor and child labor, outlawed the use of Pinkerton detectives in strikes, and eliminated yellow-dog contracts. All were ways in which he sought to improve the workplace for both men and women. He also created a state police force for maintaining industrial peace.

Abbott, Charles Conrad (b. June 4, 1843; d. July 27,1919). Archaeologist, naturalist, and author. C. C. Abbott, the son of Timothy Abbott and Susan Conrad, was born in Trenton and received his B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1861 and his M.D. in 1865. During the Civil War he served in the New Jersey National Guard. In 1867, he married Julia Boggs Olden. Abbott and his wife lived on a farm near Trenton, which Abbott called the Three Beeches.

While collecting Native American artifacts in Trenton, Abbott found stone hand axes resembling ones unearthed by contemporary archaeologists in Europe. Abbott believed that his finds represented a Paleolithic occupation of the New World coeval with that of Europe’s Old Stone Age.Shortly thereafter, Frederick Ward Putnam of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum hired Abbott and later Ernest Volk to continue collecting New Jersey artifacts. Although initially well received, Abbott’s theories came under scrutiny from prominent scholars of the day and were eventually disproven. He remains important as New Jersey’s first archaeologist, the individual who first noted in and around Trenton the extensive archaeological deposits subsequently designated the Abbott Farm National Historic Landmark.

For much of his life Abbott supported himself by writing popular books on natural history and archaeology. He also served briefly as the University of Pennsylvania Museum’s first curator of archaeology. C. C. Abbott died in Bristol, Pennsylvania, and is buried in Trenton’s Riverview Cemetery, near where he believed he had found the remains of Paleolithic man.

Abbott and Costello. Stars of burlesque, radio, film, and television, and one of America’s greatest comedy teams. Bud Abbott (b. Oct. 6,1897; d. Apr. 24,1974), born William Alexander Abbott in Asbury Park, moved from New Jersey as a child. Lou Costello (b. Mar. 6, 1906; d. Mar. 3,1959), born Lou Cristillo, grew up in Paterson and remained a favorite son long after he left.

Abbott and Costello teamed up in 1936 on the burlesque circuit, honing their act in the Costello family’s garage. A typical skit cast Abbott as a well-dressed, smooth-talking con man, and Costello, in his trademark baggy pants, skinny tie, and round hat, as his befuddled sidekick. Their rendition of an old burlesque skit, "Who’s on First?”became their signature routine. Their performance on the Kate Smith Hour, a nationally broadcast radio show, in the late 1930s, made Abbott and Costello overnight stars. The routine, in which Abbott attempts to inform Costello of the odd names of baseball players—"Who’s on first, What’s on Second, I Don’t Know is on third’—endures as a metaphor for situations of hopeless confusion. Time magazine named "Who’s on First?” the best comedy routine of the twentieth century.

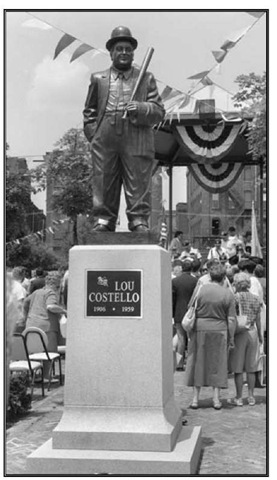

Bronze statue of Lou Costello, Paterson.

After moving to California around 1940, Abbott and Costello appeared in the first of their thirty-six films, A Night in the Tropics. Their next film, Back Privates, established "the boys” as a box-office smash. They also starred in their own radio show and television series. The team routinely inserted references to Paterson and New Jersey into their skits, and several Abbott and Costello movies premiered at Paterson’s Fabian Theater.

Occasional feuds and personal tragedy punctuated Abbott and Costello’s long friendship. In 1943 Costello’s baby son and namesake drowned in the family pool in Sherman Oaks, California. Heavy gamblers, Abbott and Costello were forced to pay hefty fines following audits by the Internal Revenue Service. The team broke up in 1957.

In 1992, Paterson residents erected a statue of Lou Costello with a baseball bat resting on his shoulder, a nod to "Who’s on First?”

Abbott v. Burke. In 1985 the New Jersey Supreme Court again faced the constitutionality of how the state funds its public school system, a question previously addressed in the 1973 Robinson v. Cahill case. Over the course of the next sixteen years the court was asked by several poor urban school districts to declare that the Public School Education Act of 1975 violated the "thorough and efficient” clause of the New Jersey constitution. In responding to this claim, the justices realized that they would be in "an area where confrontation between the branches of government [judicial and legislative] is not only a distinct possibility but has been an unfortunate reality.” The court noted the existence of judicial opinions from twenty-one states challenging the funding of public education on constitutional grounds. None of the other state court opinions had the unique attribute of this case: "an educational funding system specifically designed to conform to a prior court decision, having been declared constitutional by the Court but now attacked as having failed to achieve the constitutional goal.” Thus the court was not able to look elsewhere for an answer, but had to fashion an answer through its interpretation of the state constitution.

Despite legislative action, funding and spending disparities between poor urban districts and rich suburban districts had worsened. Although the justices rejected a complete overhaul of New Jersey’s system of financing education, they concluded that the Public School Education Act failed to provide disadvantaged students with the chance to compete. Mindful of the socioeconomic hardships faced by the urban poor and the impact these hardships have on the quality of education, the justices concluded that these socioeconomic differences increased the need for additional spending. The justices also noted that the level of education offered to students in some of the poorer urban districts was tragically inadequate. These districts suffered by comparison to the richer districts in each of the indicators set forth by the legislature to constitute a thorough and efficient education, such as teacher/student ratios and teacher experience and level of education.

The remedy imposed was to amend the Public School Education Act to create "special need” districts, "so as to assure that poorer urban districts’ educational funding is substantially equal to that of property-rich districts.” Contrary to public perception, the court did not itself create "special need” districts, currently classified as "Abbott districts,” but relied upon the classification of "urban aid districts” by the Department of Community Affairs. The justices instructed the legislature that the means of such funding "cannot depend on the budgeting and taxing decisions of local school boards.”

The court identified the poorer urban areas; however, the court left it to the legislature and the commissioner of education to add or delete specific school districts based upon spending calculations and formulas. The justices declared the minimum aid provision of the act unconstitutional since this formula was counterequalizing. The sole function of this aid was to enable richer districts to spend even more, "thereby increasing the disparity of educational funding between richer and poorer.” Despite the substantial breadth of their ruling, the justices once again declined to address the state equal-protection claim presented by the plaintiffs—that wealth-based disparity is causing educational disparity.

Since 1985 there have been six Abbott v. Barke decisions. They have imposed remedies consisting of the creation of thirty Abbott districts, several revisions in the Public School Education Act and Regulations, and the creation of an $8.5 billion Public School Construction Fund (of which $6 billion was allocated to the Abbott districts) due to the sixteen-year history of "chronic failure” of local districts to attain the statewide academic standards. Despite these decisions, the urban/suburban rift in the New Jersey educational community continues to grow as the state tries to resolve the discrepancies.

Aberdeen. 5.45-square-mile township in northernmost Monmouth County. The area was settled in 1686, largely by Scots Presbyterians. First called New Aberdeen, it was part of Middletown Township from 1693 to 1857, when it became Matawan Township. With Matawan Borough, Aberdeen, at the southern periphery of central New Jersey’s clay deposits, has been home to numerous pottery, tile, and brick industries. The area’s former role as Monmouth County’s major manufacturing region was in part a result of its transportation network, including the former Freehold and New York Railroad and the former New York and Long Branch Railroad (now the North Jersey Coast Line), and its location on Matawan Creek (a narrow, now-silted stream). The Cliffwood Beach section attained prominence in the 1920s as a waterfront resort, a role lost to changing recreational patterns and beach erosion. Aberdeen’s character as a residential suburb was solidified in the early 1960s by William J. Levitt’s construction of Strathmore, a development of nearly two thousand houses built in ten sections, which propelled population growth that decade from 7,359 to 17,680. In 1977 Matawan Township voters narrowly chose to change the municipality’s name to Aberdeen to help it develop an identity separate from Matawan Borough.

In 2000 Aberdeen’s population of 17,454 was 79 percent white and 12 percent black. Median household income was $68,125. For complete census figures, see chart, 129.

Abolition. Efforts to abolish slavery in New Jersey began soon after the Dutch introduced the first slaves. As early as 1685, individual Quakers argued for slavery’s end. In 1715 Quaker John Hepburn penned the first publication in New Jersey opposing slavery. But widespread opposition to slavery was slow in coming, even among the Friends.

In 1730 the Friends of the Shrewsbury Quarterly Meeting thought slave buying was wrong and should be prohibited. The leadership of the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, however, argued that abolition would create "contention and uneasiness” among Friends, "which should be carefully avoided.” A more liberal Quaker leadership emerged in the 1750s and in 1754 recommended against slave-holding. By 1774, Quakers selling or transferring slaves for any reason but to free them faced disownment, and in 1776 the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting banned slavery completely among its members.

The Methodists condemned slavery in 1780 and vowed in 1785 that they would "not cease to seek its destruction, by all wise and prudent means.” In 1787 the Presbyterian Synod urged the use of "prudent measures to secure the eventual final abolition of slavery in America.” By 1837, the Methodists had banned slaveholding among their membership.

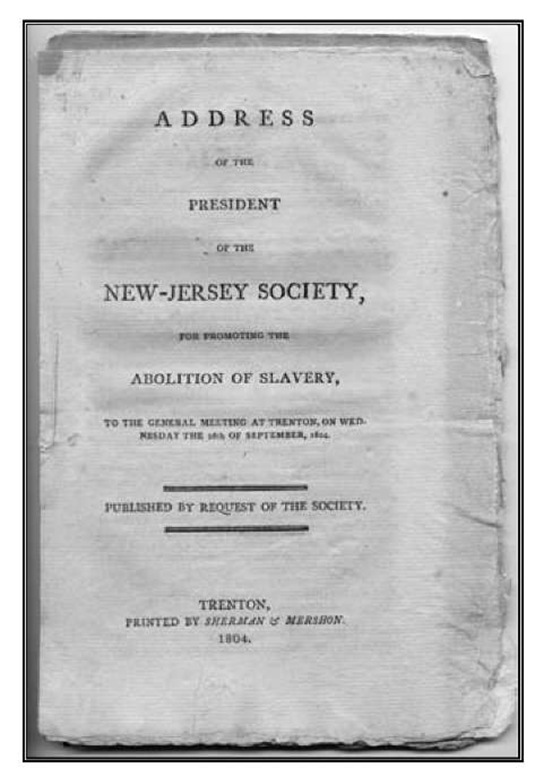

Title page of an antislavery pamphlet by William Griffith, president of the New Jersey Society foi Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, 1804.

The colonial government of New Jersey attempted to limit the slave population through import duties passed between 1713 and 1767. In 1781 a petition to the legislature recommended a gradual emancipation plan similar to Pennsylvania’s Act of 1780, and an abolition society soon formed at Burlington. Legislation was passed in 1786 to prevent the importation of slaves, to authorize their manumission, and to protect them from abuse. In the same year, another abolition society was organized in Trenton. Gov. William Livingston urged the legislature in 1788 to take steps toward eventual emancipation. Another society had formed in Princeton that year, and in 1790, while a member of the legislature, John Witherspoon, president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), introduced another plan for gradual abolition.

The New Jersey Abolition Society was organized in 1792 to coordinate all antislavery activity in the state. A gradual emancipation act introduced in the legislature in 1795 failed by one vote. Nevertheless, the Abolition Society’s success with strategically engaged lawsuits and intense lobbying began to erode slavery’s weakening base of support. When a constituent branch of the society was formed in Trenton in 1803, its members successfully carried the fight into Hunterdon and Sussex counties, where resistance to abolition was strong. Victory came in 1804, when the legislature passed an act for the gradual abolition of slavery.

Having achieved its primary goal of an abolition law, the Abolition Society went into a rapid decline. The Burlington society’s minutes end in 1809, and only the Trenton society continued to operate until the New Jersey Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery was officially declared dissolved in 1817.

A slave-trading scandal in New Brunswick in 1819 provoked renewed antislavery efforts. Led by William Griffith, a new abolition society focused its energies on protecting fugitives and combating the illicit slave trade. By the 1830s, it had given way to the New Jersey branch of the American Anti-Slavery Society, which strongly denounced the gradualist methods of its predecessors and demanded an immediate end to slavery.

New Jersey’s first abolitionist newspaper began in Boonton in 1844, and in the same year abolitionist lawyers unsuccessfully argued before the New Jersey Supreme Court that the preamble to the state’s new constitution abolished slavery outright. A final blow came when a new abolition law passed by the legislature in 1846 ended slavery, though in name only. By 1850, the abolition movement in New Jersey was all but dead.