The central nervous system (CNS) represents one of the most metabolically active systems in the body. The metabolic demands of the brain must be met with the blood supply to this organ. Normal cerebral blood flow is about 50 mL/100 g of brain tissue/min. Thus, a brain of average weight (1,400-1,500 g) has a normal blood flow of 700 to 750 mL/min. Even a brief interruption of the blood supply to the CNS may result in serious neurological disturbances. A blood flow of 25 mL/100 g of brain tissue/min constitutes ischemic penumbra (a dangerously deficient blood supply leading to loss of brain cells). A blood flow of 8 mL/100 g of brain tissue/min leads to an almost complete loss of functional neurons. Consciousness is lost within 10 seconds of the cessation of blood supply to the brain.

Arterial Supply of the Brain

Blood supply to the brain is derived from two arteries: (1) the internal carotid artery and (2) the vertebral artery. These arteries and their branches arise in pairs that supply blood to both sides of the brain. The basilar artery is a single artery located in the midline on the ventral side of the brain. The branches of the basilar artery also arise in pairs. The origin of the arteries supplying blood to the brain, their major branches, and the neural structures supplied by them are described in the following sections.

Internal Carotid Arteries

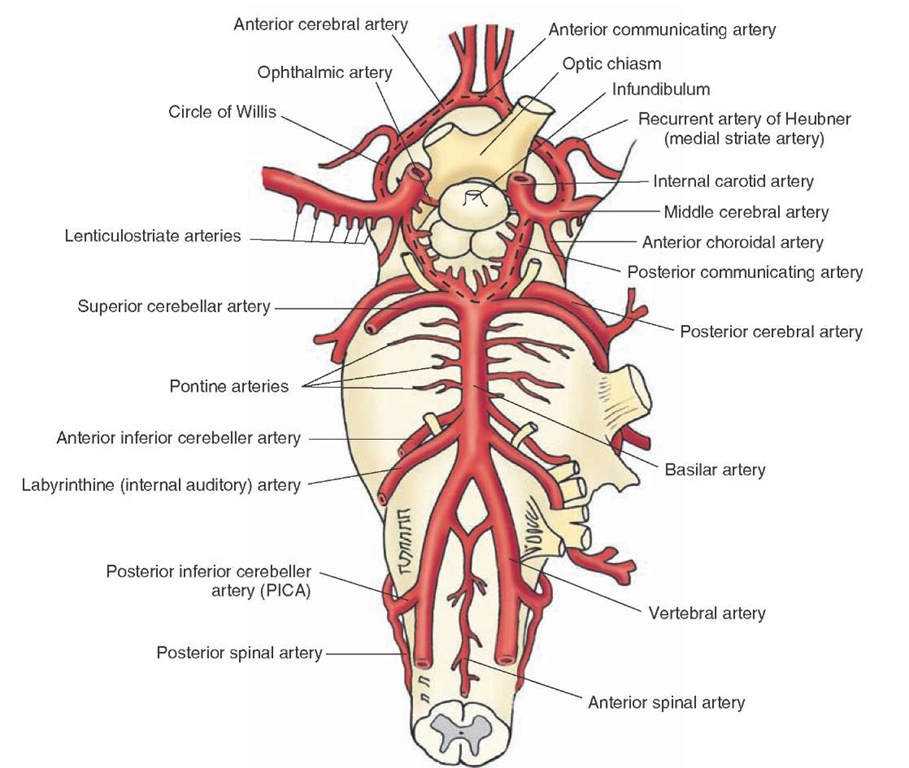

The internal carotid arteries (Fig. 4-1) arise from the common carotid artery on each side at the level of the thyroid cartilage and enter the cranial cavity through the carotid canal. They penetrate the dura just ventral to the optic nerve. The main intracranial branches of each internal carotid artery are described in the following sections.

The Ophthalmic Artery

The ophthalmic artery (Fig. 4-1) enters the orbit through the optic foramen and gives rise to the central artery of the retina, which supplies the retina and cranial dura. Interruption of blood flow in the ophthalmic artery causes loss of vision in the ipsilateral eye.

FIGURE 4-1 The internal carotid artery and vertebro-basilar system. Major branches of the internal carotid artery are the ophthalmic artery, the posterior communicating artery, the anterior choroidal artery, the anterior cerebral artery, and middle cerebral artery. The main branches of the vertebral artery are the anterior spinal artery and the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. The basilar artery is formed by the confluence of the two vertebral arteries; its major branches are the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, the pontine arteries, the superior cerebellar artery, and the posterior cerebral artery. Note the cerebral arterial circle (circle of Willis; marked by a dashed black line). The optic chiasm and infundibulum are shown for orientation purposes.

The Posterior Communicating Artery

The posterior communicating artery (Fig. 4-1) arises at the level of the optic chiasm and travels posteriorly to join the posterior cerebral arteries. Small branches arising from this artery supply blood to the hypophysis, infundibulum, parts of the hypothalamus, thalamus, and hippocampus.

The Anterior Choroidal Artery

The anterior choroidal artery (Fig. 4-1) arises near the optic chiasm and supplies the choroid plexus located in the inferior horn of the lateral ventricle, the optic tract, parts of the internal capsule, hippocampal formation, glo-bus pallidus, and lateral portions of the thalamus.

The Anterior Cerebral Artery

At the level just lateral to the optic chiasm, the internal carotid artery divides into a smaller anterior cerebral artery and a larger middle cerebral artery (Fig. 4-1). The anterior cerebral artery travels rostrally through the inter-hemispheric fissure. It supplies blood to the medial aspect of the cerebral hemisphere, including parts of the frontal and parietal lobes. This artery also supplies blood to the postcentral gyrus (which is concerned with the processing of sensory information from the contralateral leg) and pre-central gyrus (which is concerned with the motor control of the contralateral leg). Occlusion of one of the anterior cerebral arteries results in loss of motor control (paralysis) and loss of sensation in the contralateral leg. The symptoms associated with the occlusion of the anterior cerebral artery are consistent with the somatotopic representation of body parts in the cortex. The leg and foot are represented in the medial surface of the precentral and postcentral gyri. It should be noted that when the parts of the body are drawn in terms of the degree of their cortical representation (i.e., in the form of a somatotopic arrangement), the resulting disproportionate figure that is depicted is commonly called a homunculus.Other structures supplied by the anterior cerebral artery include the olfactory bulb and tract, anterior hypothalamus, parts of the caudate nucleus, the internal capsule, the putamen, and the septal.

The Anterior Communicating Artery At the level of the optic chi-asm, the anterior communicating artery connects the anterior cerebral arteries on the two sides (Fig. 4-1). A group of small arteries arising from the anterior communicating and anterior cerebral arteries penetrates the brain tissue almost perpendicularly and supplies blood to the anterior hypothalamus, including the preoptic and supra-chiasmatic areas. Intracranial aneurysms commonly occur (20%-25% incidence) on the anterior communicating artery or at the junction of this artery and the anterior cerebral artery. These aneurysms may cause visual deficits due to their proximity to the optic chiasm.

The main branches of the anterior cerebral artery are described in the following sections.

The Medial Striate Artery (Recurrent Artery of Heubner). The medial striate artery (Fig. 4-1), also called recurrent artery of Heubner, arises from the anterior cerebral artery at the level of the optic chiasm and supplies blood to the antero-medial part of the head of the caudate nucleus and parts of the internal capsule, putamen, and septal nuclei. The medial striate and the lenticulostriate arteries penetrate the perforated substance.

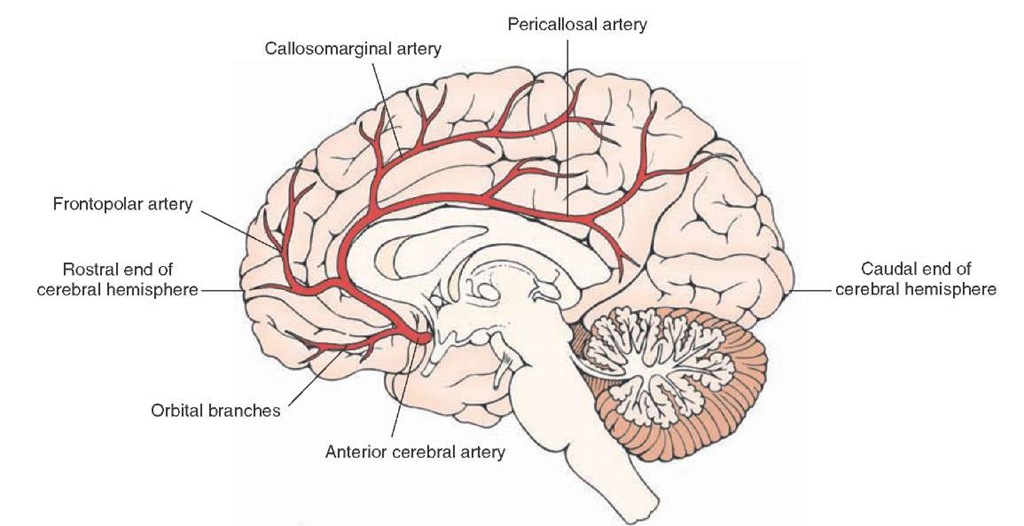

The Orbital Branches. The orbital branches (Fig. 4-2) arising from the anterior cerebral artery supply the orbital and medial surfaces of the frontal lobe.

The Frontopolar Branches. The frontopolar branches (Fig. 4-2) of the anterior cerebral artery supply medial portions of the frontal lobe and lateral parts of the convexity of the hemisphere.

FIGURE 4-2 Major branches of the anterior cerebral artery (viewed from the medial side). The branches include the orbital branches, the frontopolar branches, the callosomarginal artery, and the pericallosal artery. The rostral and caudal ends of the cerebral hemisphere are shown for orientation purposes.

The Callosomarginal Artery. The callosomarginal artery (Fig. 4-2), arising from the anterior cerebral artery, supplies the paracentral lobule and portions of the cingulate gyrus.

The Pericallosal Artery. The pericallosal artery (Fig. 4-2) continues caudally along the dorsal margin of the corpus callosum and supplies the precuneus (the portion of the parietal lobe caudal to the paracentral lobule).

The Middle Cerebral Artery

As mentioned earlier, the internal carotid artery divides into the smaller anterior cerebral artery and the larger middle cerebral artery (Figs. 4-1 and 4-3A) at the level just lateral to the optic chiasm. Branches of the middle cerebral artery supply blood to the lateral convexity of the cerebral hemisphere, including parts of the temporal, frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes. The middle cerebral artery gives off the following major branches.

The Lenticulostriate Branches. This group of small arteries (Figs. 4-1 and 4-3A) are the first branches of the middle cerebral artery. The lenticulostriate branches supply the putamen, caudate nucleus, and anterior limb of the internal capsule.

The Orbitofrontal Artery. The orbitofrontal artery supplies parts of the frontal lobe (Fig. 4-3B).

FIGURE 4-3 Major branches of the middle cerebral artery. (A) Coronal section showing the lenticulostriate, the precentral (pre-Rolandic), central (Rolandic), and the parietal and temporal branches. The internal carotid, anterior cerebral, and anterior communicating arteries; the optic chiasm; the internal capsule; and the temporal lobe of the brain are shown for orientation purposes. (B) Top view showing the anterior, middle, and posterior temporal arteries; the angular artery; the posterior and anterior parietal arteries; the central (Rolandic) and precentral (pre-Rolandic) arteries; and the orbitofrontal arteries.

The Precentral (Pre-Rolandic) and Central (Rolandic) Branches. The precentral and central arteries (also called pre-Rolandic and Rolandic arteries, respectively [Fig. 4-3, A and B]) supply different regions of the frontal lobe.

The Anterior and Posterior Parietal Arteries. The anterior and posterior parietal arteries (Fig. 4-3B) supply different regions of the parietal lobe.

The Angular Artery. The angular artery (Fig. 4-3B) supplies the angular gyrus.

The Anterior, Middle, and Posterior Temporal Arteries. The anterior, middle, and posterior temporal arteries (Fig. 4-3, A and B) supply different regions of the temporal lobe. Branches of the posterior temporal artery also supply the lateral portions of the occipital lobe.

Vertebro-Basilar Circulation

This system includes the two vertebral arteries, the basi-lar artery (which is formed by the union of the two vertebral arteries), and their branches (Fig. 4-1). This arterial system supplies the medulla, pons, mesencephalon, and cerebellum. Different branches of the vertebral artery are described in the following sections.

The Vertebral Artery

The vertebral artery (Fig. 4-1) on each side is the first branch arising from the subclavian artery. It enters the transverse foramen of the sixth cervical vertebrae, ascends through these foramina in higher vertebrae, and eventually enters the cranium through the foramen magnum. In the cranium, at the medullary level, each vertebral artery gives off the anterior spinal artery, the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, and the posterior spinal artery.

The Anterior Spinal Artery

At the confluence of the two vertebral arteries, two small branches arise and join to form a single anterior spinal artery (Fig. 4-1). This artery supplies the medial structures of the medulla, which include the pyramids, medial lemnis-cus, medial longitudinal fasciculus, hypoglossal nucleus, and the inferior olivary nucleus. It should be recalled that the axons contained within the pyramid originate in the cerebral cortex.At the caudal end of the medulla, near its juncture with the spinal cord, most of the fibers contained within the pyramid pass to the contral-ateral side through a commissure, the pyramidal decussation.

The Posterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery

The posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA [Fig. 4-1]) arises from the vertebral artery and supplies the regions of the lateral medulla that include the spinothalamic tract, dorsal and ventral spinocerebellar tracts, descending sympathetic tract, descending tract of cranial nerve V, and nucleus ambiguus. Occlusion of this artery produces Wallenberg’s syndrome, which is characterized by damage to the lateral medulla where the nucleus ambiguus is located. Damage to the nucleus ambiguus, which provides inner-vation to laryngeal muscles, results in lack of coordination in speech (dysphonia), disturbance in articulation (dysarthria), and dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing). The PICA also supplies the vermal region and inferior-lateral surface of the cerebellar hemisphere.

The Posterior Spinal Artery

The posterior spinal artery (PSA) is the first branch of the vertebral artery in the cranium in about 25% of cases. However, in a majority of cases (75%), the PSA arises from the PICA (Fig. 4-1). In the caudal medulla, this artery supplies the fasciculus gracilis and cuneatus as well as the gracile and cuneate nuclei, spinal trigeminal nucleus, dorsal and caudal portions of the inferior cere-bellar peduncle, and portions of the solitary tract and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve.