Unangan![]() , "People." The Unangan were formerly and are occasionally known as Aleut, possibly meaning "island" in a Siberian language. The Unangan consisted of perhaps nine named subdivisions, each of which spoke an eastern, a central, or a western dialect.

, "People." The Unangan were formerly and are occasionally known as Aleut, possibly meaning "island" in a Siberian language. The Unangan consisted of perhaps nine named subdivisions, each of which spoke an eastern, a central, or a western dialect.

Location Unangan territory included the Pribilof, Shumagin, and Aleutian (west to the International Date Line) Islands and the extreme west of the Alaska Peninsula. Fog and wind, perhaps more than anything else, characterized the climate. In contrast to most of the Arctic region, the ocean remains ice free year-round.

Population The Unangan population was between 16,000 and 20,000 people, although there may have been fewer, in the early eighteenth century. There were about 4,000 Unangan in the early 1990s, of whom perhaps half lived away from their traditional lands. The Unangan people are known to have enjoyed relatively great longevity.

Language Unangans spoke three dialects of Aleut, a member of the Eskaleut language family.

Historical Information

History Ancestors of the Unangan probably moved east and then south across the Bering land bridge and then west from western Alaska to arrive in their historical location, where people have lived for at least 7,000 years. Direct cultural relationships have been established to people living in the region as long ago as 4,000 years.

The Russians, arriving in the 1740s, quickly recognized the value of sea otter and other animal pelts. For a period of about a generation, they tried to compel the Unangan to hunt for them, mainly by taking hostages and threatening death. The natives resisted, and there was much bloodshed during that time. However, after losing between a third and half of their total population they gave up the struggle and were made to do the Russians’ bidding. Unangan men were forced to hunt sea mammals from Alaska to southern California for the Russian-American company. Large-scale population movements date from that period and lasted well into the twentieth century.

The strong influence of Russian culture dates from that period and includes conversion to the Russian Orthodox church by the early nineteenth century, when the worst of the Russian excesses ended. Other significant Russian influences include metal tools, steam baths, and larger kayaks, with sails. An Unangan orthography was created about that time, allowing the people to read and write in their own language.

Unangan hunters had come into increasing conflict with their Inuit and Indian neighbors as they were forced to go farther and farther afield for pelts. By the early nineteenth century, disease as well as warfare had diminished their population by about 80 percent. Survivors were consolidated onto 16 islands in 1831, but, by that time, Unangan culture had suffered a near-fatal blow.

The Russians left and the Americans took over around 1867, increasing fur hunting and driving the sea otter practically to extinction. The town of Unalaska had become an important commercial center by 1890. Fox trapping and canneries had become important to the local economy by the early twentieth century. Much of the Aleutian chain was designated as a national park in 1913. Some religious and government schools were opened in the early to mid-twentieth century. Still, the people endured high tuberculosis rates in the 1920s through the 1940s, and there were few, if any, village doctors.

The Japanese attacked the Aleutian Islands during World War II, capturing residents of Attu. The United States removed almost all Unangans west of Unimak Island, interning them in camps in southeast Alaska. Many people, especially elders who normally transmitted cultural beliefs and practices to the young, died during that period owing to the poor conditions in the camps. When the people returned home after the war, they found that many of their homes and possessions had been destroyed. As a result, many villages were abandoned.

The commercial fishing and cash economy grew sharply after the war. Most Unangan worked at the lowest levels of the economy. By then, Unangan children were attending high school in Sitka (Bureau of Indian Affairs) and Anchorage. Alaska received statehood in 1958. Nine years later, the native people founded the Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN) and the Aleut League. Unangan were included in the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), after initial rejection because of their high percentage of Russian blood.

Religion The people may have recognized a generative deity associated with the sun that had overall responsibility for souls as well as hunting success. They also recognized good and evil spirits, including animal spirits. These were the supernatural beings that influenced people’s lives on a day-to-day basis. Adult men made offerings to the spirits at special sacred places and used a number of various charms, talismans, and amulets for protection. They also undertook spirit dances, although mainly to intimidate women and children into proper behavior Souls were said to migrate between three worlds: earth, an upper sphere, and a lower sphere. Shamans mediated between the material and spiritual worlds. Their vocations were considered to be predetermined; that is, they did not seek a shamanic career. They had the usual responsibilities concerning hunting, weather, and curing.

Various winter masked dances and ceremonies were designed to propitiate the spirits. Perhaps the major ceremony was a memorial feast held 40 days following a death. Death was an important rite of passage. Some groups mummified dead bodies in order to preserve that person’s spiritual power. A whaler might even remove a piece of the mummy for assistance, but this custom was also considered potentially dangerous.

Government The eldest man usually led independent house groups, although all household leaders functioned as a council. One house group in a village was generally considered first among equals, the head of that group functioning as village chief if he merited the position. These leaders had little or no coercive power but mainly coordinated decision making over issues of war and peace and camp moves. They might become wealthy in part from receiving a share of subordinates’ catch (wealth consisted not only of furs and skins but also of dentalium shells, amber, and slaves). This position could be inherited in the male line. In addition, there were also special leaders known as strong men. These people received special training but tended to die early.

Customs Among the Unangan, descent was probably matrilineal. Their class structure was probably derived from Northwest Coast cultures. The three hereditary classes were wealthy people (chiefs and nobles), commoners, and a small number of slaves, mainly women. The first two groups were usually related. Harmony, patience, and hard work were key values. Speech was judicious in nature, and silence was generally respected.

Villages claimed certain subsistence areas and evicted or attacked trespassers. Numerous formal partnerships between both men and women served to bind the community together. Berdaches were men who lived and worked as women. Women sewed and processed and prepared food. Truly incorrigible people might be put to death upon agreement by the village elders.

Boys moved from their mother’s to their maternal uncle’s home in mid-childhood. The uncle took over primary responsibility for raising the boy, with the father playing more of a supporting role. Boys were strengthened, toughened, and rigorously trained from a very early age for the life of a kayak hunter. When a girl began menstruating, she was confined for 40 days, during which time her joints were bound, in theory so they would not ache in her old age. She was also subject to a number of food and behavioral restrictions and admonishments and was allowed to cure minor illness, the people believing that she possessed special curative powers during these times.

Girls could marry even before they reached puberty, but boys were expected to wait until they were at least 18; that is, when they were capable providers. Most marriages were monogamous, except that particularly wealthy men might have more than one wife. Men performed a one- or two-year bride service. Cross cousins (children of a mother’s brothers or a father’s sisters) were considered potential, even preferred, spouses. Divorce was rare.

Winter was the time for ceremonies as well as social visits between communities. Village chiefs invited another community and extended great hospitality toward their guests. These visits featured wrestling, storytelling, and dance contests. Some dancers wore wooden masks to invoke spirits.

Some men paddled out to sea at the end of their lives, never to return. In fact, suicide tended to be seen in a positive light for a number of reasons. The insides of most corpses were removed and replaced with grass. Following this procedure, bodies would remain in the house, either in a corner or in a cradle over the bed, for up to several months. They were eventually buried in a flexed position in the house, either under the floor or within the walls. Central and eastern people also mummified some corpses, caching the mummies in warm, dry, volcanic caves. Widows and widowers were subject to a period of special behavioral restrictions, including some joint binding.

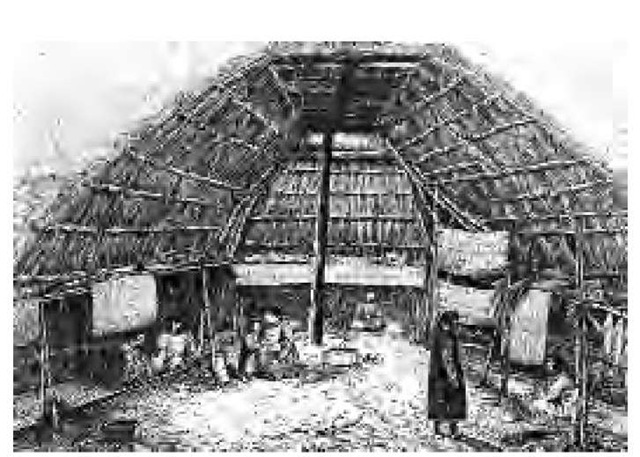

Dwellings Typical villages contained roughly 200 people, although up to 2,000 people may have populated some eastern communities. Rectangular, semiexcavated houses (barabara) were made of a driftwood and whalebone frame covered with matting and turf. Sizes varied widely. The average may have been about 35 to 60 feet long by about 15 to 30 feet wide. These houses held perhaps 40 people or several nuclear families related through the male line. The largest houses may have been up to 240 feet long by 40 feet wide, holding up to 150 people.

Sleeping compartments separated by grass mats ringed a large central room. Mats also served as flooring. Entrance was gained via a ladder placed through an opening in the roof. Cooking was generally outside the house. Large houses also served as dance halls.

The interior of a habitation on Unalaska Island, 1778. These houses held approximately 40 people, or several nuclear families related through the male line. The largest may have been up to 240 feet long by 40 feet wide and held up to 150 people. Sleeping compartments separated by grass mats ringed a large central room. Mats also served as flooring.

Diet Depending on location, the people ate mainly sea lions, but also seals, sea otter, octopus, and some walrus. Most sea mammals were hunted by men in kayaks. Sea otters were hunted communally, in a surround, or clubbed on shore. Men who hunted sea otter avoided women for a month prior to the hunt.

There was also some whaling, especially in the west. Whaling was highly ritualized. For instance, men who had harpooned a whale retired to a special hut to feign illness, so that the whale would fall ill. Whaling privileges and powers could be inherited through the male line.

Other types of food included large and small game on the eastern islands and mainland. Important fish species included cod, flounder, halibut, herring, trout, and salmon. People ate birds, fowl, and their eggs, the latter gained mainly by climbing up or down steep cliffs. They also gathered seaweed, shellfish, roots, and berries, depending on location. Unangans tended to eat much of their food raw, although there was some pit cooking.

Key Technology Sea mammals were harpooned or clubbed. Atlatls helped give velocity to a harpoon throw. Eastern people hunted large game with the bow and arrow. Whale lances may have had poison tips. Fishing equipment included spears, nets, and wooden and tooth hooks. Birds were taken with bolas and darts, although puffins were snared and netted. Women used chipped stone semilunar knives for hide preparation and fish cleaning.

Most tools were made from stone and bone. Other important material items included sewn skin bags and pouches, some wooden buckets and bowls, sea lion stomach containers, tambourine drums, and spruce-root and grass baskets. Stone lamps burned sea lion blubber for light and heat. Cordage came from braided kelp or sea lion sinew. The people started fires with a wooden drill and flint sparks on sulphur and bird down. A highly developed counting system allowed them to reckon in five figures.

Trade Unagnan people traded both goods and ideas with Northwest Coast groups such as the Tlingit and Haida as well as with Yup’ik and Alutiiq peoples. Exports included baskets, sea products, and walrus ivory. The people imported items such as shells, slaves, blankets, and hides.

Notable Arts Art objects included carved wooden dancing masks and decorative bags. Women wove fine spruce-root and grass baskets and decorated mats with geometric designs. Ivory carvings of the great creative spirit were hung from ceiling beams in houses, and other objects were decorated with ivory carvings as well. The Unangan were also known for their painted wooden hats. Storytelling was highly developed. Clothing decoration included feathers, whiskers, and fringe. Some items were painted, mainly with geometric patterns.

A sixteenth-century illustration of the Inuit. Note that the hunter is holding an atlatl with a three-pronged spear. The atlatl was used to throw sealing darts or harpoons and helped give velocity to a harpoon throw.

Transportation Men hunted in one- or possibly two-person kayaks. Larger skin-covered open boats were used for travel and trade but not for whaling.

Dress Women and men wore long parkas of sea otter or bird skin (men wore only the latter material). The women’s version had no hood, only a collar. Men also wore waterproof slickers made of sewn sea lion gut, esophagus, or other such material. Particularly in the east, sealskin boots had soles of sea lion flipper. Boots were less common in the west. The people used grass for socks.

Men also wore wooden visors, painted and decorated with sea lion whiskers. They wore painted conical wooden hats on ceremonial occasions. Other ceremonial clothing was made of colorful puffin skins. Both sexes wore labrets of various materials. They tattooed their faces and hands and wore bone or ivory nose pins. Women wore sea otter capes.

Unangan men wore wooden visors, such as this one, painted and decorated with sea lion whiskers. They also wore painted conical wooden hats on ceremonial occasions.

War and Weapons The Unangan fought their Inuit neighbors, especially the Alutiiq, as well as themselves (especially those who spoke different dialects). Small parties often launched raids for women and children slaves or to avenge past wrongs. The people used stone and bone weapons, such as the bow and arrow, lances, wooden shields, and slat armor. Slain enemies were often dismembered, in the belief that an intact body, though dead, could still be dangerous. Prisoners might be tortured. On the other hand, high-status captives might be held for ransom or used as slaves.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations Unangan live on the Alaska coast, Aleutian Islands, Pribilof Islands, and Commander Islands. Communities include Atka, Akutan, Belkofski, Cold Bay, False Pass, Ivanof Bay (see Alutiiq), King Cove, Nelson Lagoon, Nikolski, Paulof Harbor, St. George Island, St. Paul Island, Sand Point, Squaw Harbor, and Unalaska. There are various forms of government, including traditional structures and those modeled on the Indian Reorganization Act. Elected village governments own no land.

Economy Economic development is recognized as key to survival. Many villages are in economic partnerships with seafood companies. Most jobs may be found with the fishing and military industries as well as other governmental bodies at lower levels.

Legal Status ANCSA granted some traditional lands to the Aleut Corporation and to village corporations but not to the tribes. The Aleut Corporation represents Unangans under ANCSA.

Daily Life Most Unangan are of the Russian Orthodox faith. Most also live in wood frame houses. There is a considerable degree of intermarriage with non-Unangans. The position of the corporations visa-vis the tribes has made for some bitter interfamily and intervillage divisions. Political sovereignty remains a major goal for most people. Some public schools feature courses in the Unangan language. A cultural facility on Bristol Bay is planned.