Pomo![]() l, a group of seven culturally similar but politically independent villages or tribelets. This Pomo word means roughly "those who live at red earth hole," possibly a reference to a local mineral.

l, a group of seven culturally similar but politically independent villages or tribelets. This Pomo word means roughly "those who live at red earth hole," possibly a reference to a local mineral.

Location Traditionally, the Pomo lived about 50 miles north of San Francisco Bay, on the coast and inland, especially around Clear Lake and the Russian River. Today there are roughly 20 Pomo rancherias in northern California, especially in Lake, Mendocino, and Sonoma Counties. Pomo Indians also live in regional cities and towns.

Population Roughly 15,000 in the early nineteenth century, the Pomo population stood at 4,766 in 1990. About one-third of these lived on tribal land.

Language "Pomo" was actually seven mutually unintelligible Pomoan (Hokan) languages, including Southern Pomo, Central Pomo, Northern Pomo, Eastern Pomo, Northeastern Pomo, Southeastern Pomo, and Southwestern Pomo (Kashaya).

Historical Information

History Pomo prehistory remains murky, except that the people became a part of a regional trading system at about 1500. By the late 1700s, the Spanish had begun raiding Southern Pomo country for converts, and Hispanic influence began to be felt in Pomo country. Russian fur traders also arrived to brutalize the natives during this time. Their primary method of attracting Indian help was to attack a village and kidnap the women and children, who were then held as hostages (slaves) while the men were forced to hunt fur-bearing animals. In 1811 the Russians established a trading post at Fort Ross, on Bodega Bay (abandoned in 1841).

Hundreds of Pomos accepted the Catholic faith at local Spanish missions after 1817. In 1822, California became part of the Mexican Republic. Mexicans granted land to their citizens deep within Pomo country and enforced the land grants with strict military control. Thousands of Pomos died of disease (mainly cholera and smallpox) during the 1830s and 1840s, and Mexican soldiers killed or sold into slavery thousands more. Deaths from disease were doubly killing: Since the Pomo attributed illness to human causes, as did many native peoples, the epidemics also brought a concurrent rise in divisive suspicions and a loss of faith in traditions.

A bad situation worsened for the Pomo after 1849, when Anglos flooded into their territory, stealing their land and murdering them en masse. Survivors were disenfranchised and forced to work for their conquerors under slavelike conditions. A number of Pomos—perhaps up to 200—were killed by the U.S. Army in 1850. In 1856, the Pomo were "rounded up" and forced to live on the newly established Mendocino Indian Reserve. The government discontinued the reserve eleven years later, however, leaving the Indians homeless, landless, and with no legal rights.

Later in the century, Pomos mounted a project to buy back a land base. Toward this end, they established rancherias (settlements) and worked as cheap migrant agricultural labor, returning home in winter to carry on in a semitraditional way. By 1900, however, Pomos had lost 99 percent of these lands through foreclosure and debt. The remaining population were viewed with hatred by most whites, who practiced severe economic and social discrimination against them. This situation provided fertile ground for Ghost Dance activity and the Bole-Maru (dreamer) cult, an adaptive structure that may have helped ease their transition to mainstream values.

Missionaries in the early twentieth century worked with Indians to promote Indian rights, antipoverty activities, education, and temperance. By that time, Pomos had begun using the courts and the media to expand their basic rights and better their situation. A key Supreme Court decision in 1907 recognized the rancherias as Indian land in perpetuity. More Pomo children began going to school; although the whites kept them segregated, the people mounted legal challenges designed to win equal access. After World War I, Indian and white advocacy groups proliferated, and reforms were instituted in the areas of health, education, and welfare. Indians gained a body of basic legal rights in 1928.

During the 1930s, the Depression forced a return to more traditional patterns of subsistence, which led to a period of relative prosperity and revitalization. At the same time, contact with other, non-Indian migratory workers brought new ideas about industry and labor organization to the Pomo. Intermarriage also increased. Women gained more independence and began to assume a greater role in religious and political affairs around this time.

After World War II, the United States largely relinquished its role in local Indian affairs to the state of California, which was unprepared to pick up the slack. Several rancherias were terminated, and services declined drastically, leading to a period of general impoverishment. Since the 1950s, however, various Indian groups have been active among the Pomo in helping them to become more politically and economically savvy, and some state agencies have stepped in to provide services. The Clear Lake Pomo were involved in the takeover of Alcatraz Island in 1969-1971, reflecting their involvement in the pan-Indian movement. Beginning in the 1970s, many Pomo bands successfully sued the government for rerecognition, on the grounds that Bureau of Indian Affairs promises of various improvements had not been kept.

Religion The Kuksu cult was a secret religious society, in which members impersonated a god (kuksu) or gods in order to obtain supernatural power. Members observed ceremonies in colder months to encourage an abundance of wild plant food the following summer. Dances, related to curing, group welfare, and/or fertility, were held in special earth-covered dance houses and involved the initiation of 10- to 12-year-old boys into shamanistic, ritual, and other professional roles. All initiates constituted an elite secret ceremonial society, which conducted most ceremonies and public affairs.

Secular in nature, and older than the Kuksu cult, the ghost-impersonating ceremony began as an atonement for offenses against the dead but evolved into the initiation of boys into the Ghost Society (adulthood). A very intense and complex ceremony, especially among the Eastern Pomo, it ultimately became subsumed into the Kuksu cult.

The Bole-Maru in turn grew out of the Ghost Dances of the 1870s. The leader was a dreamer, and a doctor, who intuited new rules of ceremonial behavior. Originally a revivalistic movement like the Ghost Dance, this highly structured, four-day dance ceremony incorporated a dualistic worldview and thus helped Indians to step more confidently into a Christian-dominated society.

Other ceremonies included a women’s dance, a celebration of the ripening of various crops, and a spear dance (Southeastern, involving the ritual shooting of boys). Shamans were healing or ceremonial professionals. They warded off illness, which was thought to be caused by ghosts or poisoning, from individuals as well as the community. Doctors (mostly men) were a type of curing specialist, who specialized in herbalism, singing, or sucking.

Government The Pomo were divided into tribelets, each composed of extended family groups of between 100 and 2,000 people. Generally autonomous, each tribelet had its own recognized territory. One or more hereditary, generally male, minor chiefs headed each extended family group. All such chiefs in a tribelet formed a council or ruling elite, with one serving as head chief, to advise, welcome visitors, preside over ceremonies, and make speeches on correct behavior. Groups made regular military and trade alliances between themselves and with non-Pomos. A great deal of social control was achieved through a shared set of beliefs.

Customs The Pomo ranked individuals according to wealth, family background, achievement, and religious affiliation. Most professions, such as chief, shaman, or doctor, required a sponsor and were affiliated with a secret society. The people recognized many different types of doctors. Bear doctors, for instance, who could be male or female, could acquire extraordinary power to move objects, poison, or cure.

The position was purchased from a previous bear doctor and required much training. Names were considered private property.

Boys, who were taught certain songs throughout their childhoods, were presented with a hair net and a bow and arrow around age 12. For girls, the onset of puberty was a major life event, with confinement to a menstrual hut and various restrictions and instructions. Pomos often married into neighboring villages. The two families arranged a marriage, although the couple was always consulted (a girl was not forced into marriage but could not marry against the wishes of her family). Methods of population control included birth control, abortion, sexual restrictions, infanticide, and occasionally geronticide. The dead were cremated after four days of lying in state. Gifts, and occasionally the house, were cremated along with the body.

Dwellings Along the coast, people built conical houses of redwood bark against a center pole. Inland, the houses were larger pole-framed, tule-thatched circular or elliptical dwellings. Other structures included semisubterranean singing houses for ceremonies and councils and smaller pit sweat houses.

Diet Hunters and gatherers, the Pomo mainly ate seven kinds of acorns. They hunted deer, elk, antelope, fowl, and small game. Gathered foods included buckeyes, pepperwood nuts, various greens, roots, bulbs, and berries. Most foods were dried and stored for later use. Coastal groups considered dried seaweed a delicacy. In some communities the good food sources were privately owned.

Key Technology Items included baskets (cooking pots, containers, cradles, hats, mats, games, traps, and boats); fish nets, weirs, spears, and traps; tule mats, moccasins, leggings, boots, and houses; and assorted stone, wood, and bone tools. Feathers and beads were often used for design. Hunting tools included the bow and arrow, spear, club, snares, and traps.

Trade The Pomo participated in a vast northern California trade group. Both clamshell beads and magnesite cylinders served as money. People often traded some deliberately overproduced items for goods that were at risk of becoming scarce. One group might throw a trade feast, after which the invited group was supposed to leave a payment. These kinds of arrangements tended to mitigate food scarcities.

Exchange also occurred on special trade expeditions. Objects of interest might include finished products such as baskets as well as raw materials. The Clear Lake Pomo had salt and traded it for tools, weapons, furs, and shells. All groups used money of baked and polished magnesite as well as strings of clam shell beads. The Pomo could count and add up to 40,000.

Notable Arts Pomo baskets were of extraordinarily high quality. Contrary to the custom in many tribes, men assisted in making baskets. Pomos also carved highly abstract petroglyphs beginning about 1600.

Transportation Coastal residents crossed to islands on driftwood rafts bound by vegetal fiber. The Clear Lake people used boats of tule bound with split grape leaves.

Dress Dress was minimal. Such clothing as people wore they made from tule, skins, shredded redwood, or willow bark. Men often went naked. Women wore waist-to-ankle skirts, with a mantle tied around the neck that hung to meet the skirt. Skin blankets provided extra warmth. A number of materials were used for personal decoration, including clamshell beads, magnesite cylinders, abalone shell, and feathers. Bead belts and neck and wrist bands were worn as costume accessories and as signs of wealth.

War and Weapons Poaching (trespass), poisoning, kidnapping or murder of women or children (usually for transgressing property lines), or theft constituted most reasons for warfare. Pomos occasionally formed military alliances among contiguous villages. Warfare began with ritual preparation, took the form of both surprise attacks and formal battles, and could end after the first casualty or continue all the way to village annihilation. Women and children were sometimes captured and adopted. Chiefs of the fighting groups arranged a peace settlement, which often included reparations paid to the relatives of those killed. Hunting or gathering rights might be lost or won as a result of a battle. Pomos often fought Patwins, Wappos, Wintuns, and Yukis. They made weapons of stone, bone, and wood.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations In addition to cities and towns in and around northern California, Pomos live at the following rancherias: Big Valley (Pomo and Pit River, Lake County; 38 acres; 90 Indians), Cloverdale (Mendocino County; no formal land base; 1 resident), Dry Creek (Sonoma County; 1906; 75 acres; 38 Indians), Coyote Valley (Mendocino County), Sulphur Bank (Lake County; 1949; 50 acres; 90 Indians), Grindstone (Glenn County), Lytton (Sonoma County), Hopland (Mendocino County; 1907; 48 acres; 142 Indians), Stewart’s Point (Sonoma County; 40 acres; 86 Indians [Kashia Band]), Manchester-Point Arena (Mendocino County; 1909; 363 acres; 178 Indians), Middletown (Lake County; 1910; 109 acres), Potter Valley (Mendocino County; 200 tribal members; 10 acres; 1 Indian resident), Redding (Shasta County; 31 acres; 79 Indians), Redwood Valley (Mendocino County; 58 acres; 14 Indians), Robinson (Lake County; 103 acres; 113 Indians), Sugar Bowl (Scott’s Valley Band of Pomo Indians [Pomo and Wailaki], Lakeport County), Sherwood Valley (Mendocino County; 350 acres; 9 Indians), Upper Lake (Lake County; 1907; 19 acres; 28 Indians), Guidiville (Mendocino County), and Laytonville (Cahto-Pomo, Mendocino County; 200 acres; 129 Indians). They also live at the Pinoleville Reservation (1911; Mendocino County; 99 acres [almost half owned by non-natives]; 280 members) and the Round Valley Reservation (1864; 30,538 acres; Achomawi, Concow, Nomlaki, Wailaki, Wintun, Yuki, and Pomo; Mendocino County; 577 Indians). Population figures are as of 1995. Rancherias and reservations are generally governed by elected tribal councils.

A Pomo woman weaving a basket. Pomo baskets were of extraordinarily high quality. Unlike the custom in many tribes, men also assisted in making baskets.

The Pinoleville Band of Pomo Indians lives on the Pinoleville Reservation, which is located north of Ukiah, Mendocino County. The reservation was "unterminated" and its boundaries reestablished in the 1980s.

Economy Pomo country is still relatively poor. People engage in seasonal farm work as well as skilled and unskilled work. Some work with federal agencies, and some continue to hunt and gather their food.

Legal Status The Big Valley Rancheria of Pomo and Pit River Indians, the Cloverdale Rancheria of Pomo Indians, the Coyote Valley Band of Pomo Indians, the Dry Creek Rancheria of Pomo Indians, the Elem Indian Colony of Pomo Indians of the Sulphur Bank Rancheria, the Grindstone Rancheria, the Guidiville Rancheria, the Hopland Band of Pomo Indians of the Hopland Rancheria, the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians of the Stewart’s Point Rancheria, the Laytonville Rancheria (Cahto-Pomo), the Lytton Rancheria, the Manchester Band of Pomo Indians of the Manchester-Point Arena Rancheria, the Middletown Rancheria of Pomo Indians, the Pinoleville Reservation of Pomo Indians, the Potter Valley Rancheria of Pomo Indians, the Redding Rancheria of Pomo Indians, the Redwood Valley Rancheria of Pomo Indians, the Robinson Rancheria of Pomo Indians, the Round Valley Reservation, the Scott’s Valley Band of Pomo Indians, the Sherwood Valley Rancheria of Pomo Indians, and the Upper Lake Band of Pomo Indians of Upper Lake Rancheria are all federally recognized tribal entities.

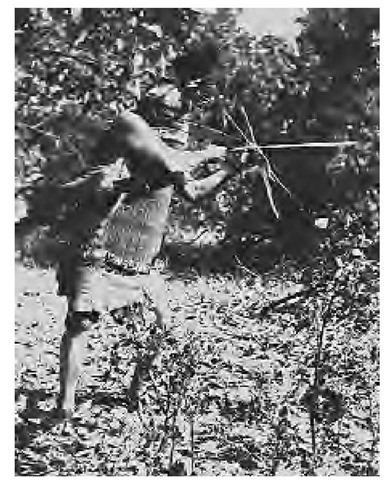

A Pomo’s chin-to-hip armor, made of two layers of willow and hazel shoots, offered protection from arrows at the expense of mobility.

The Sherwood Rancheria, the Yokayo Rancheria, and the Yorkville Rancheria are all privately owned; their Pomo communities are seeking federal recognition.

Daily Life Despite the years of attempted genocide and severe dislocation, Pomo culture remains alive and evolving. The extended family is still the main social unit. Pomo languages are still spoken, and some traditional customs, including ritual restrictions, traditional food feasts, some ceremonies, intercommunity ceremonial exchange, singing and dancing, and seasonal trips to the coast, are still performed. Pomo doctors cure illness caused by poisoning; non-Indian doctors are called in for some other medical problems. Pomo basket weavers enjoy an international reputation.

Many Christian Pomos practice a mixture of Christian and traditional ritual. Some Pomos would like to unite politically, but the lack of such a tradition acts as a brake on the idea. However, various transgeographic (not limited to one formal or even informal community) social and political organizations do exist to bring the Pomo people together and advance their common interests. The relatively large number of non-natives on some of the Pomo rancherias may be explained by the effects of termination and the loss of individual Pomo land (to taxes and foreclosure) and its subsequent sale to whites. The struggle continues to reacquire a land base and to win recognition (or rerecognition) for some bands. Pinoleville must deal with environmentally hazardous industries established within its borders.

The pan-Pomo Ya-Ka-Ama Indian Center features a plant nursery among other economic development, educational, and cultural projects. The intertribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council works to restore heavily logged areas using modern native techniques.