The eight species of living bears are characterized by having massive skulls, large (25-780 kg) and heavily built bodies, relatively short and powerful limbs, short tails, a shuffling plantigrade gait, and an omnivorous diet aided by a keen sense of smell and large crushing molar teeth. This uniformity of body plan has a relatively recent evolutionary history, however, with the two earlier ursid radiations, the Amphicynodontinae and Hemicyoninae, exhibiting a greater array of dental and postcra-nial adaptations than the living bears. Throughout their approximately 37 million year history, ursids have maintained a Holarc-tic distribution, migrating into Africa on at least four separate occasions and into South America at least once, and were the dominant carnivorans of Eurasia during much of the Oligocene and Miocene. Morphology-based analyses indicate that Ursidae is the sister taxon to Pinnipedia, a phylogenetic hypothesis that has also received some support from molecular studies.

I. Ursid Fossil Record

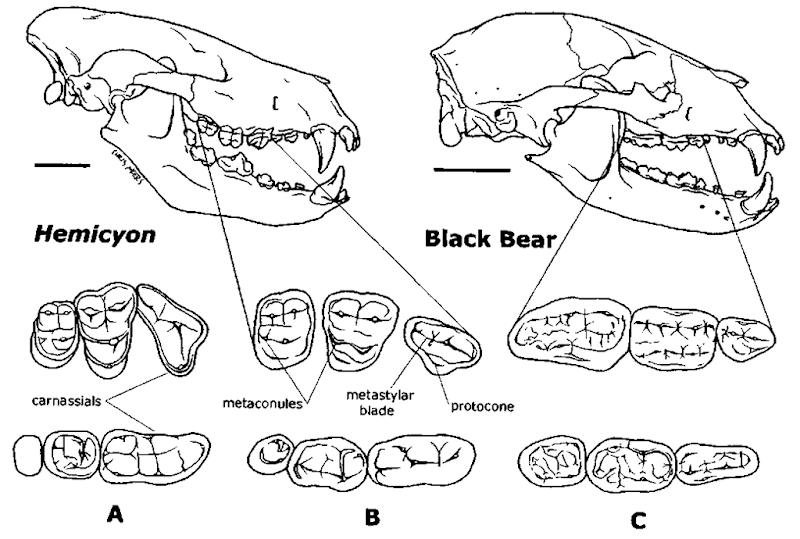

The earliest recognized ursids, members of the subfamily Amphicynodontinae, first appeared in the late Eocene and early Oligocene fossil records of North America and Eurasia. Before going extinct at the end of the early Miocene, this pa-raphyletic assemblage of carnivorans gave rise to both the hemicyoninine and ursine ursids and possibly to the basal members of Pinnipedia. Amphicynodonts were generally small to medium sized (< 15 kg), plantigrade or possibly semidigiti-grade, and tended to retain a primitive dentition possessing a well-developed pair of carnassial teeth for shearing, triangular rather than quadrate upper molars, and relatively small posterior molar teeth (Fig. 1A). Apomorphic characters shared by these earliest ursids with all later members of the family, however, include a posteriorly wide basioccipital bone, a large broad protocone on the upper carnassial, initial reduction of the parastyle and paraconule on the upper molars (both lost in later ursids), and the presence of a posterior shelf or heel on the lower second molar (Tedford et al, 1994). A more derived am-phicynodont was the early Miocene, sea otter-like Kolponomos. Collected from coastal deposits along Oregon and Washington. This genus has been reconstructed as semiaquatic with sensitive lips and tactile vibrissae, powerful neck muscles, and broad cheek teeth used to locate, pry off, and then crush, respectively, shelled marine invertebrates found attached to rocky substrates (Tedford et al, 1994). These workers have also argued that among known ursids, Kolponomos occupies the position of sister taxon to Pinnipedia.

The second ursid radiation was initiated in the late Oligocene of Eurasia. The Hemicyoninae were the first ursids to attain large body size (upwards of 200 kg) and the only ursids to evolve digitigrady, an adaptation for cursoriality that supports the interpretation of these animals as active predators comparable in many respects to canids (Hunt, 1998). The dentition of hemicyonines is derived relative to amphicynodonts in that the upper carnassial has a retracted protocone and a shortened metastylar blade, and the upper molars are quadrate due to enlargement and migration of the metaconule (Fig. IB). Hemicyonines migrated into North America on several occasions and into Africa at least once, but by the latest Miocene they were extinct throughout their geographic range.

The subfamily Ursinae, although primarily a late Miocene and Pliocene radiation, first appeared in the late Oligo-cene?-early Miocene fossil record of North America. The earliest member of the group, Ursavus, was a small to mid-sized Holarctic and plantigrade form that exhibited some of the dental specializations characteristic of later bears, including further reduction (compared to hemicyonines) of the upper carnassial and the development of low-crowned, elongate molars with wrinkled enamel (Hunt, 1998). In modern bears such as Ursus, these traits are taken to an extreme with broadening and lengthening of the molar teeth (Fig. 1C), providing an immense grinding surface for processing vegetation. Derived from a species of Eurasian Ursavus, Ursus first appeared about 5 million years ago (mya) migrating into North America about 4.3 mya and into North Africa about 1 mya. The only bears to have reached South America belong to the Ursinae and include Arc-todus, which arrived less than 2 mya, and the living spectacled bear (Tremarctos), which has no South American fossil record.

Figure 1 Comparison of skulls and dentitions of representative members of the three ursid radiations■ Lateral views of the skulls of the Hemicyon (Miocene) and the living black bear (Ursus americanus) and occlusal vieivs of P4-M1 (above) and ml-m3 (below) for Amphicynodon (A, Oligocene), Hemicyon (B), and Ursus americanus (C). Note the relative reduction in size of the carnassial teeth and the increased surface area of the posterior molars in living bears. Figures of Amphicynodon and Hemicyon are from Cirot and Bonis (1992) and Colbert (1939), respectively. Scale bar: 5 cm.

II. Phylogenetic Relationships of Living Ursids

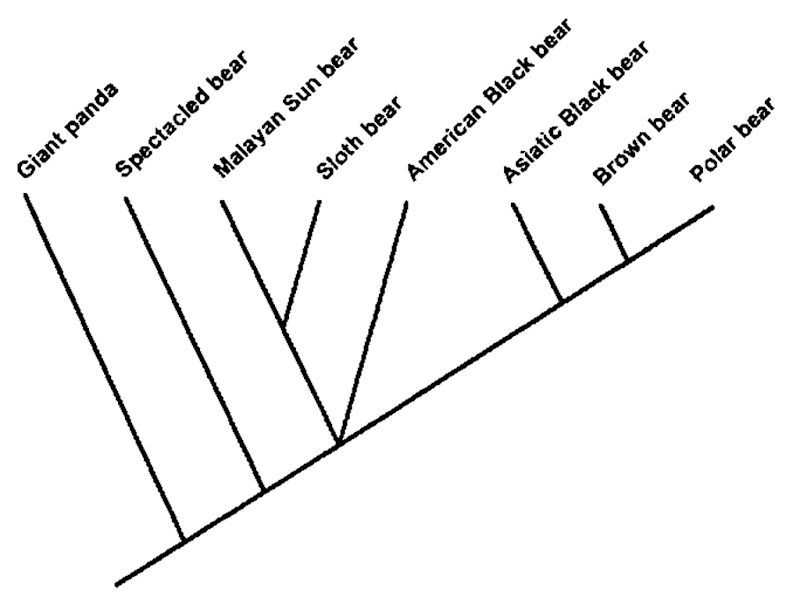

The eight species of living ursid are currently allocated to as few as three (Ailuropoda, Tremarctos, and Ursus) and as many as five (additionally Helarctos and Melursus) genera, all of which are monospecific except Ursus. Tremarctos oniatus (spectacled bear) and A. melanoleucus (giant panda) are successive out-groups to the remaining six species (Fig. 2), and although there has been some contention as to whether the giant panda should be included within the family at all, it is now widely accepted that Ailuropoda diverged from other members of Ursinae during the early Miocene. The most recent phylogenetic analysis incorporating both molecular and morphologic data sets (Bininda-Emonds et al, 1999) suggests that the Malayan sun bear (II. malayanus) and sloth bear (M. ursinus) are sister taxa, that the Asiatic black bear (U. thibetanus) is the sister taxon to the clade brown bear (17. arctos) + polar bear (17. maritimus), and that the position of the American black bear (17. americanus) is unresolved with respect to these other two clades (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 A cladogram depicting phylogenetic relationships among the eight species of living ursid: the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleucus), spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus), Malayan sun bear (Ursus malayanus), sloth bear (U. ursinus), American black bear (U. americanus), Asiatic black bear (U. thibetanus), brown bear (U. arctos), and polar bear (U. maritimus).

The only marine-adapted ursine, the polar bear, is thought to have diverged from the brown bear between 100,000 and 250,000 years ago probably as a result of glacial advances that isolated northern and southern populations. Ancestors of the modern polar bear became adapted for life on the sea ice, evolving a denser, hollow fur for protection against the Arctic cold and morphologic characteristics such as sharper claws and carnassial teeth for grasping and shearing through the skin of captured seals. Despite these and other ecological and morphological differences between the two species, polar bears and brown bears are still capable of producing fertile offspring and some biologists have suggested that the Barren Ground grizzly may be such a hybrid.