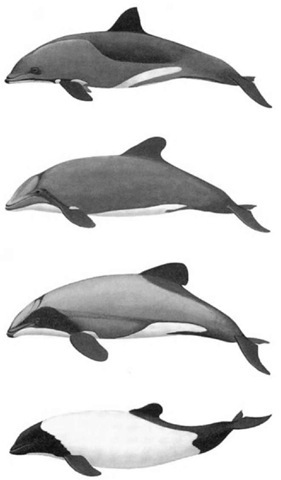

The four dolphins of the genus Cephalorhynchus are small, coastal species found only in Southern Hemisphere waters (Fig. 1). Haviside’s dolphin (C. heavisidii) occurs off the west coast of South Africa and Namibia. Hectors dolphin (C. hectori) is found solely off New Zealand. The Chilean dolphin (C. eutropia) is found in the coastal waterways of Chile and along the exposed west coast. The remaining species, Commer-son’s dolphin (C. commersonii), has the strangest distribution. Its principal stronghold is in the inshore waters of Argentina and in the Strait of Magellan, but it also occurs at the Falkland Islands and has an isolated population 8500 km away at the Ker-guelen Islands, in the Indian Ocean. The Kerguelen Commer-son’s dolphins are larger, retain the darker juvenile coloration into adulthood, and have some skeletal and genetic differences. It appears that this population was founded by only a very few individuals, perhaps as recently as 10,000 years ago.

Cephalorhynchus dolphins are among the smallest dolphins. Indeed, in length. Hector’s dolphins from New Zealand’s South Island (maximum 145 cm; ca. 50 kg) and South American Com-merson’s dolphins (maximum 146 cm; ca. 45 kg) are the smallest of all dolphins (franciscanas are longer, but weigh less). Both Hector’s and Commerson’s dolphins have isolated populations in which individuals grow larger. Commerson’s dolphins at Kerguelen grow to 174 cm (86 kg), and the few North Island Hector’s dolphins reach at least 152 cm (65 kg). In both these species females are 5-10% larger than males. Far fewer Haviside’s and Chilean dolphins have been measured so it is not clear whether females are also larger in these species. Heavi-side’s dolphins reach about 174 cm (ca. 75 kg), and Chilean dolphins reach at least 167 cm (ca. 63 kg).

Figure 1 The four Cephalorhynchus species, top to bottom: Haviside’s, Chilean, Hector’s, and Commerson’s dolphins. Pieter A. Folkens/Higher Porpoise DG.

All four species share similar morphology. They are all small, blunt-headed (hence the frequent mistake of calling them porpoises), chunky dolphins with rounded, almost paddle-shaped flippers. The most characteristic feature of the genus is the dorsal fin, which is proportionately large and with a rounded, convex trailing edge (like a Mickey Mouse ear; Hector’s, Commerson’s, and Chilean dolphin) or triangular (Haviside’s dolphins). In color pattern, Chilean dolphins and Hector’s dolphins are most similar.

I. Distribution and Abundance

Of the four species, only Hector’s dolphin has been surveyed throughout its range. It is most common along the east and west coasts of the South Island between 41° 30′ and 44° 30′S, with hot spots of abundance at Banks Peninsula and between Karamea and Makawhio Point. These South Island east coast and west coast populations are genetically distinct, as is the very small population occurring on the west coast of the North Island between 36° 30′ and 38° 20′S. An apparently isolated population exists in Te Wae Wae Bay, on the Southland coast. Recent surveys suggest South Island populations number ca. 1900 (east coast) and ca. 5400 (west coast). The species is rarely seen more than 8 km from shore. We have not seen it in water more than 75m deep.

South American Commerson’s dolphins are found off the east coast between Rio Negro (40°S) and Cape Horn (55° 15′S) down into the Drake Passage (61° 50′S) and also at the Falkland Islands. They are common between Peninsula Valdez and Tierra del Fuego (42° to 54°S) and very common in the Straits of Magellan, where an aerial survey in 1984 suggested a population of around 3200. At Kerguelen, Commerson’s dolphins are restricted to the immediate vicinity of the islands, where they are seen most frequently on the eastern side in the Golfe du Morbihan.

Haviside’s dolphins are found on the west coast of Southern Africa from 17° 09′S) on the Namibian coast to around Cape Town (34° 13′S). Sightings are clustered between Walvis Bay and Cape Town. There are no estimates of abundance.

Chilean dolphins have been seen over a very wide latitudinal range, from Valparaiso (33° S) to near Cape Horn (55° 15′S), on both open and sheltered coasts. They are seen regularly in only a few places, however, including Valdivia, Golfo de Arauco, and near Chiloe. The total population appears to be very small (low thousands at most). Suggestions that the species is becoming very rare (Leatherwood, personal communication) are worrying and impossible to refute without dedicated survey work.

All Cephalorhynchus species favor waters of less than 200 m deep and are often seen in the surf zone, especially in summer.

II. Reproduction and Population Biology

Reproduction has been studied thoroughly only in Hector’s dolphins and Commerson’s dolphins, but the limited information available for Haviside’s and Chilean dolphins suggests they are similar. Females bear their first calf between 6 and 9 years, in spring to late summer. Males reach sexual maturity between 5 and 9 years. Mating and calving occur in spring to late summer, and the gestation period is around 10-11 months. The maximum ages so far found in this genus are 20 (Hector’s dolphin) and 18 (Commerson’s dolphin).

Studies of individually identified Hector’s dolphins suggest that mature females calve every 2-4 years. Late maturity, a relatively short life, and long intervals between calves inevitably result in a low population growth rate. Modeling studies have shown that Hector’s dolphin populations, in the absence of human impact, would be expected to grow by about 2% per year.

III. Diet

All four species feed on a wide variety of coastal prey, focusing on benthic and small pelagic schooling fish and squid. The South American species supplement their fish/squid diet with crustaceans (mysids, euphausids, and Munida spp.) and, strangely, algae. Haviside’s dolphins are apparently alone in preying on octopus to any significant degree. The diet of Hector’s dolphins is more varied on the South Island east coast, where eight species of fish and squid make up 80% of die diet by mass, than it is on the corresponding west coast (where four species make up 80%).

IV. Movement

Individual dolphins in this genus appear to be seasonally resident in a local area. Long-running studies on Hector’s dolphins have shown that individuals usually range over about 30 km of coastline. In Haviside’s, Commerson’s, and Chilean dolphins, at least some individuals are found in local areas year-round, although inshore abundance is lower in winter. Individual Hector’s dolphins have been resighted in the same general area year-round, but they tend to spread out, form smaller groups, and range further from shore in winter. There is no evidence for large-scale migration. Despite wide-ranging surveys over more than a decade, no two sightings of the same individual Hector’s dolphin are more than 106 km apart.

V. Behavior

Small group sizes are characteristic of this genus. Although occasional sightings of more than 50 have been made, most sightings are of between 2 and 10 individuals. In high-density areas, there may be several such groups nearby. In Hector’s dolphin, these often coalesce to form a large, temporary group of 25 or so. Large groups often show boisterous behavior, such as chases, leaps, and lobtailing. Sexual displays and copulation are also more common after groups have joined. Such large groups are usually short-lived; after 10-30 min they split into small groups again. Frequently groups lose, gain, or swap members in this process. Associations among adult Hector’s dolphins are weak. It is likely that the other species are similar.

All members of the genus except Chilean dolphins are strongly attracted to boats and readily ride the bow wave. Chilean dolphins have been heavily hunted and their wariness of boats has probably been acquired. All species are thoroughly at home in turbulent water close to shore and are frequendy seen surfing.

VI. Acoustic Behavior

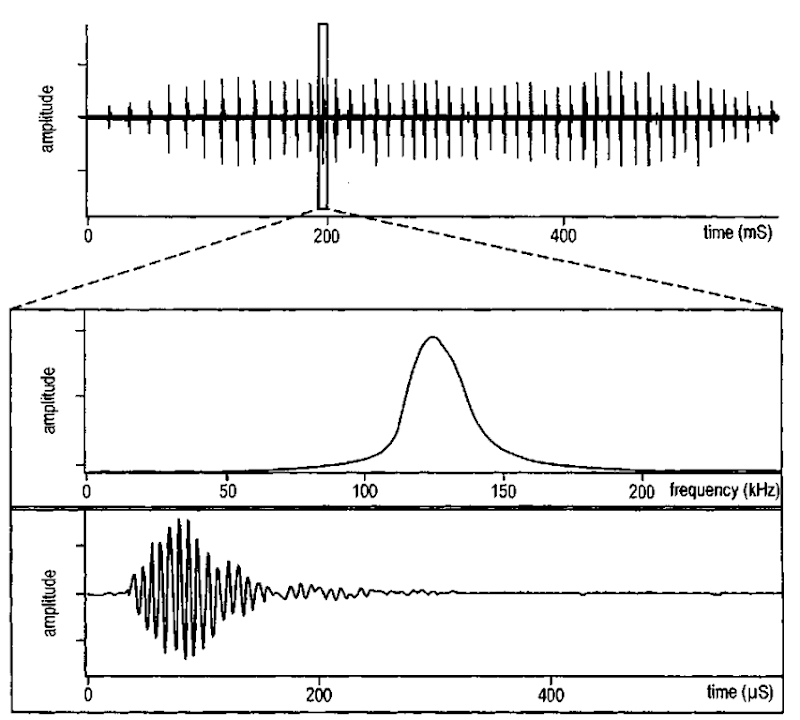

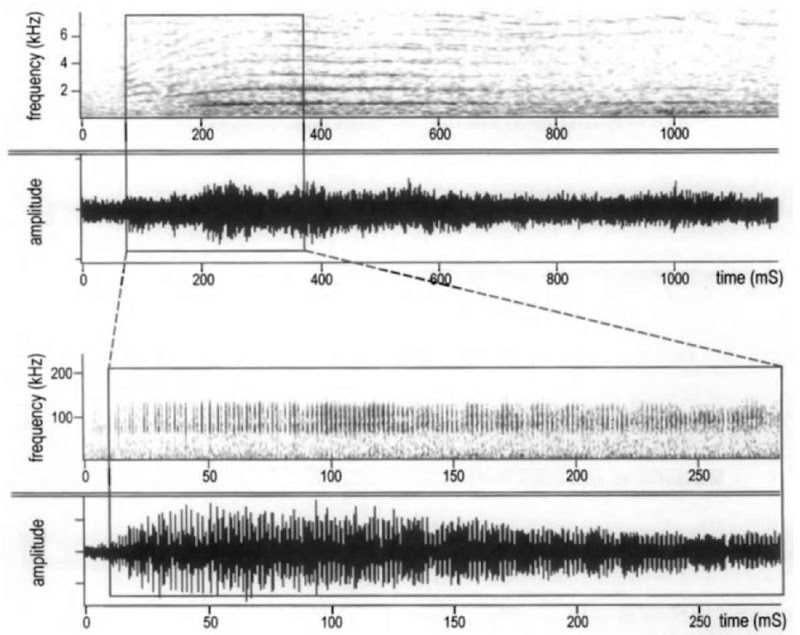

Only Hector’s dolphin has been recorded comprehensively in the wild with equipment that could capture the full range of its sounds. Almost all the sounds are short [ca. 140 |xsec (roughly 1/7000 sec)], high-frequency (ca. 125 kHz) narrow-band, ultrasonic clicks (Fig. 2) that are used in “trains” of a few dozen to several thousand. Clicks may contain one, two, or three main pulses and appear to have a role in communication as well as sonar. Complex clicks are used disproportionately in social contexts, and a particular type of click is used preferentially in feeding. Click rates can be exceptionally high (maximum 1149 clicks/sec). Such high click rates generate an audible tone of the same frequency as the click rate (Fig. 3). These signals, which sound like a “cry” or “squeal,” are strongly linked to aerial behaviors and apparently indicate excitement. “Cry”-type sounds, and the lower emphases of occasional broadband clicks, are Hector’s dolphins’ only vocalizations that are audible to humans. Very similar click and “cry”-type sounds have been described from Commerson’s dolphins.

Figure 2 A “train” of high-frequency Hector’s dolphin clicks, with a “zoomed” section showing the waveform and spectrum shown for an example click.

Haviside’s dolphin and Chilean dolphin both make the “cry” sounds just described. Neither has yet been recorded with equipment capable of recording ultrasonic frequencies. Given the close similarity of the sounds of Hector’s and Commerson’s dolphins, it is likely that the sounds of Haviside’s and Chilean dolphins will be similar also.

VII. Threats and Conservation

All four species have, at some stage, been hunted for food or bait. The South American species have fared worst: they have been hunted extensively for bait for crab pots and are reported to be no longer common in areas frequented by crab fishers. As many as 1300-1500 Chilean dolphins may have been harpooned each year near the Western Strait of Magellan in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Such hunting is now illegal, but fishers in the area are poor, and the crab processing companies supply insufficient bait. Enforcement of this law in such a remote and convoluted area is practically impossible.

All four Cephalorhynchus species suffer some degree of incidental catch in fishing gear. In South America these animals are used as bait. Hence fishers have no motive to avoid areas where captures occur and may favor them. Numbers taken currently are unknown for any of the four species. It is clear, however, that gill nets pose a larger problem than any other fishing method. In the mid-1980s an average of 57 Hector’s dolphins were caught each year in gill nets in the Canterbury region of the east coast of New Zealand’s South Island. Given the low reproductive rate of this species, it was clear that this level of catch was unsustainable. An 1170-km2 sanctuary, in which commercial gill netting is illegal and amateur gill netting is restricted to particular times and places, was established in 1989. The problem has not been entirely solved. Analysis of observed catches in the Canterbury region in 1997/1998 suggests that 18 Hectors dolphins were caught in gill nets to the north and south of the current sanctuary.

There appear to be fewer threats to Haviside’s dolphin than to the others, and it seems that Commerson’s dolphin, despite the impacts on it, is probably the most numerous member of this genus. The Chilean dolphin and Hector’s dolphin need urgent consideration. Currently there is insufficient information to judge the conservation status of Chilean dolphins. Population surveys are needed before we can say even whether the species numbers hundreds (as the most dire of the warnings imply) or thousands. In a small population of slow-breeding animals, even a very low level of directed or incidental catch can be enough to continue the decline.

Figure 3 Audible “cry” sound from Hector’s dolphin. The “zoomed” section shows that the “cry” sound is made up of high-frequency clicks emitted at a very high rate (ca. 1000 clicks/sec)

Hector’s dolphin has at least received some direct conservation action, via the Banks Peninsula Marine Mammal Sanctuary. The latest modeling suggests that this population is still declining. Hector’s dolphins off the North Island west coast are genetically as distinct from those off the South Island east coast as the South American Commerson’s dolphins are from those 8500 km away at Kerguelen. Surveys suggest that the North Island west coast population may number fewer than 100 animals. Gill netting effort along this coast is high by New Zealand standards. Population models show that this population is declining rapidly. Unless effective conservation action is taken very quickly, the outlook for North Island Hector’s dolphins is imminent extinction.