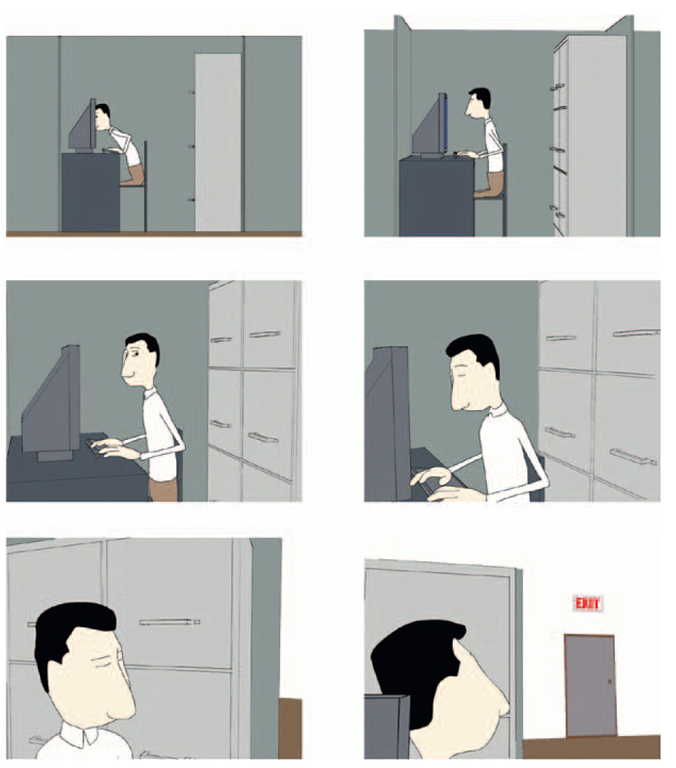

Example of flat to deep space.

LECTuRE NoTES

You, dear reader/student, now have examined working with 2D and 3D art. When combining animation media, the artist must create a world that houses these media. The next topic to explore is how to look at the world where these images come together.

The most common method (not that we are saying it is the best) is to put everything into a 3D world. Surely this has been the case as 3D objects and environments have crept into the 2D animated films. In fact, the history of animation has seen a steady progression from the use of flat, to the use of limited, to the use of deep space environments. Mostly, in 2D animation we were accustomed to flat space camera work until the multiplane camera was invented and we began to see limited and even the beginnings of deep space usage. Then a mismatch of the space usages began. We would find ourselves watching a flat space film with some usage of limited space; a 2D character would be happily telling his story while moving left and right across the screen and sometimes coming toward the camera for added depth; and then wham, we would come across a scene where the camera was suddenly liberated and moving through a 3D environment that possibly had a few 2D characters in it. Those geared toward the novel thought, “Wow!” Those geared toward the story thought, “Oh, boy!” That was a failure. We made them say, “Wow, look at the shiny thing” instead of feeling the story point more.

An example of such an incident came about when I was still in college at Ringling School of Art and Design. (I think it has changed to Ringling College of Art and Design now.) At the time, the head of the training department at Walt Disney Feature Animation’s Florida studio would visit the college every year looking for the next round of internship candidates for Disney Feature Animation. During the visits Frank, the Disney representative, would treat us by giving a sneak pre-screening of that year’s animated film. At that time, it was a great treat in the lost end of Florida to see movies before they were released. Students nowadays barely can understand how special this was, given their current ready access to bootleg videos. (Oh, and if you think you can enjoy a movie on your iPhone, please skip this topic. It is not for you.) Frank, who is a lovely energetic man, had screened a number of films during my stay at Ringling. One was Beauty and the Beast. I was studying computer animation at the time, so I was very tuned in to any use of 3D, as we all were. In the center of the film, of course, there is the great ballroom dance scene where the characters walk into a ballroom and the camera follows them. The camera then swoops up and around the ceiling of the ballroom, revealing all to be in glorious 3D and textured, and then it comes back down to swoop around the dancing 2D characters.

Many of us were stunned. What a lovely example of 3D usage. Wasn’t that beautiful? Did you see that? They were really pushing the envelope. We all marveled together.

It wasn’t until years later, when I worked at Disney and was more educated on the process and art of animation, that I realized that some considered the scene a miserable failure. In one swoop, it took the audience out of the moment and showed off the technology.

The point to take away from this is that we shouldn’t show off our technology, our pipelines. There should be reasons for everything we do, including the world we create and how we move our camera about.

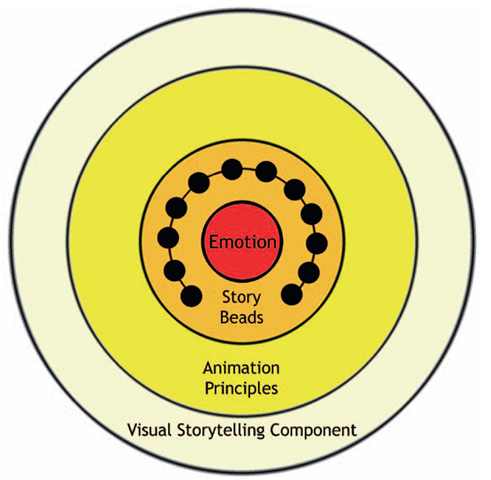

FIGURE 7.1 Bull’s-eye to keep us focused on why we set up shots.

We have come full circle then. Block, in his teachings, reminds us to tie the intensity of our visuals tightly with our story. We know this; it is usually something we do instinctively. However, you might have noticed in your research that there is a fine line between adding visual intensity to a film when the story needs it and adding visual intensity to a film at every chance. The problem with the latter is that ungoverned intensity will become numbing and ultimately lower all intensity. If you have ever seen a visual effects film where one unit shot all of the exposition and talking heads and another unit executed all of the whiz-bang fight sequences, you might have felt this problem profusely. It might have felt like this: talking heads = flat, flat, flat; fighting = wow, wow, wow. But possibly the fighting was over-wowed with each shot so that by the end you were thinking to yourself, “Is it over yet?” So to help us govern our usage of visual intensity, Block gave us the tool of charting the storybeats to the visual intensity.

FIGURE 7.2 Block’s intensity chart.

Block’s topic covers all of the actors that can be used to display visual intensity. You will want to read and understand his text. We cannot cover all the ways to apply the different actors in this topic. We have room only to discuss the actor called space. We will only be looking at the placement and movement of the characters and cameras in this topic. You will have to pursue the other subcomponents of space in your supplemental readings of Block’s topic.

It has been rumored throughout the student body that any student who takes a class of mine should not move the camera. Students give each other the advice to always have the camera locked down. They explain, “Professor O’ hates camera moves.” On the contrary, I love them. Yet they must be well done and have a reason.

When trying to understand where cameras should go and why, I found myself on a journey of exploration into many ideas, methods, glossary terms, and ideologies. Many cinematography topics explained how certain camera positions would make the audience feel. However, I found that some of the topics were talking about single shots and not looking at the whole film and how the shots related to one another. If you want to gain a holistic understanding of using the camera, I would suggest a reading list that includes the best cinematography topic you can find, along with Bruce Block’s topic, plus a concise topic about camera mechanics, and something on the placement and movement of camera blocking. I suggest the following:

1. Cinematography: Image Making for Cinematographers, Directors, and Videographers by Blain Brown, for better appreciating why shots are set up the way they are.

2. Bruce Block’s topic, The Visual Story, for learning more about how to focus on the whole structure of the film as it relates to the story.

3. The Bare Bone Camera Course for Film and Video by Tom Schroeppel, for understanding what a camera actually is.

4. Hollywood Camera Works, which is an amazing resource of tutorials and includes an exhaustive set of tutorials on where to put the camera and how to actually move it. See the companion data and the website (www.hollywoodcamerawork .us) for more information.

Of course, reading topics such as these helps to float glossary terms, rules, things to avoid, things to remember, etcetera, in your head during the creation process. However, you then need to have hands-on time in order to put these ideas into practice and develop them into a reality and not just an abstract idea. So before we continue on to techniques and methods that are being taught away from the larger context of a full story, please remember to utilize the Intensity Chart from Figure 7.2 and heed Block’s teachings when you apply these methods to your story. Do not simply apply tutorial knowledge to your films without understanding the whole of it. I mean it, or I’ll have to start lecturing to you on the neuroscience of it all. Don’t make me do it. Ding. Ding.

0eePer

If you wish to understand how the audience’s brain is working as viewers watch your film and how to use that information to your advantage when trying to elicit emotional responses out of the audience, read Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are by Joseph LeDoux and view the numerous videos out there that focus on this topic, even those shown on YouTube.

SPACE AND CAMERA MOVES

Four types of spaces can be created in your film’s world.

1. Flat space

2. Limited space

3. Deep space

4. Ambiguous space

We create these worlds and control them by our placement and movement of characters and cameras in relationship to one another. The following is a brief overview of a few of the subcomponents of space. Of course, refer to Bruce Block’s topic for a complete understanding.

Any of these spaces can be created in any medium. However, some media traditionally have lent themselves to certain special relationships.

Flat space

Character placement. On the same vertical plane, similar size, move parallel to the camera.

Camera movement. Parallel to the characters, pan, tilt, zoom. Parallax between levels. None.

The visible symptoms or subcomponents of a flat space shot can be seen in how the characters are placed and move, how the camera moves, and how little parallax is shown between the elements. Basically, all depth cues are removed from a flat space scene. Characters can be placed on the same vertical plane and be shown at similar sizes. If there are big and small characters, their size difference can be minimized by seating them or showing close-ups of the characters and not showing them standing next to one another. If the characters move at all, they should move in front of the camera and never toward it. If the camera moves, it should move parallel with the characters so that they stay a similar size throughout the shot.

Think about Charlie Brown for a moment, as he walks down the sidewalk into the front door of his house, out the back door of his house, and approaches the doghouse upon which Snoopy sleeps. If you have seen the comics or the television cartoon shows, you have seen an example of absolute flat space. The characters, in addition, are all just about the same size just to add to the flatness. It is the style of Peanuts. This style is allowed to be broken mostly when Snoopy fights the Red Baron. Okay, that’s an old reference. Let’s look at something that is in the same homage but more modern: Calvin and Hobbes. Yes, that series never will be animated, yet a similar idea can be found in those comic strips.

In fact, 2D animation is easiest when created in a flat space. It is the perspective and parallax of movements that make it more difficult to draw. On the other hand, it is more challenging, yet rewarding, to make 3D worlds into flat space. This can be done by paying careful attention to the placement of characters and the movement of the camera as well as applying a mindful usage of tonal separation and textural diffusion. (You know where to go to read more about that.)

Camera movements for a flat space shot are pans, tilts, and zooms. Basically, the camera does not move. This keeps the parallax of elements down to a minimum. This is an easy space to achieve by locking the camera and characters in one position or, if they move, moving them together. If it is so easy, why is it not done in 3D very often? Because it is also just as easy to fly that camera around for no reason whatsoever. Remember, you must have a reason to move the camera and a visual rule to describe why you are choosing to pan instead of track, or zoom instead of dolly.

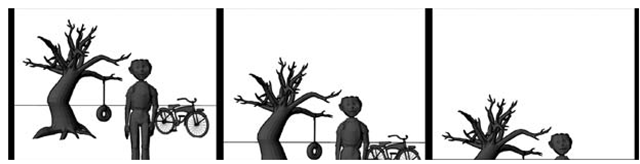

Pan

To pan a camera is to stand in one place and basically pivot the camera on its stand from one side to the other, usually to follow a character. As Figure 7.3 illustrates, when you pan the foreground elements and background elements, move across the screen at the same rate. How far apart are the foreground and background levels? You do not know, because the special clues have been removed. Note in Figure 7.3 that the distance between the branch and the boy’s head never changes.

FIGURE 7.3 Camera pan.

Tilt

Tilt is similar to pan, in that the camera is held still and pivots on its stand. For a tilt, the camera tilts up or down to follow an object. Usually something motivates the camera to move. That topic is beyond the context of this topic; pity. Tilting, like panning, moves foreground and background elements up and down the screen at the same rate. Note in Figure 7.4, as was the case in Figure 7.3, that the distance between the branch and the boy’s head never changes.

FIGURE 7.4 Camera tilt.

Zoom

The act of zooming is done by a push of a button or a twist of a lens to change the focal distance. (In Maya, this is the focal length.) This action scales all characters, foreground and background, at the same rate.

FIGURE 7.5 Camera zoom.

If you aren’t quite sure about what a 3D world would be like in flat space, think about your grandfather holding the video camera. Not all grandfathers, but many, do not move much when they hold the video camera. They stand in one place watching the soccer game. They pan the camera from left to right across the field, tilt the camera up to watch the ball as it flies into the air, and use the zoom to gain a closer look at their prize grandson playing defense. As long as the soccer players run across the field and do not run toward the grandfather, you have an example of flat space.

Before continuing, please note that flat space does not mean that you must use the 2D medium. The same space can be created in 3D or live action. Students who are new to the concept of defining space sometimes confuse medium with spatial relationships.

In the hands-on section, we will take a 3D world and compress it to create a flat space scene that has been inspired by the Cohen Brothers being inspired by Busby Berkeley a la The Big Lebowski.