Abstract

Cardiomyopathy is a generic term for any heart disease in which the heart muscle is involved and functions abnormally. Recent developments and ongoing research in cardiology have led to descriptions of previously less recognized and/or incompletely characterized cardiomyopathies. These entities are being increasingly noticed in adult patient populations. Primary care providers, hospitalists, emergency medicine physicians and cardiovascular specialists need to be aware of the clinical features of these illnesses and the best strategies for diagnosis and management. In this topic, we discuss the etiologies and diagnostic methods for identifying Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy and ways to manage this entity. This cardiomyopathy is caused by intense emotional or physical stress leading to rapid, severe but reversible cardiac dysfunction. It mimics myocardial infarction with changes in the electrocardiogram and echocardiogram, but without obstructive coronary artery disease. This pattern of left ventricular dysfunction was first described in Japan and has been referred to as "tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy," named after a fishing pot with a narrow neck and wide base that is used to trap octopus. This syndrome is also known as "apical ballooning syndrome", "ampulla cardiomyopathy", "stress cardiomyopathy", or "broken-heart syndrome".

Introduction

In recent years, a new cardiac syndrome with transient left ventricular dysfunction has been described which was first identified in Japanese patients. This new entity has been referred to as "tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy" or "apical ballooning", named after the particular shape of the end-systolic left ventricle on ventriculography. [1] To date, tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) has also been reported in western populations. Emotional or physical stress usually precedes the presentation of this cardiomyopathy. The mechanistic explanation responsible for this acute but reversible contractile dysfunction is still not known. Multivessel epicardial coronary artery vasospasm, coronary microvascular dysfunction or spasm, impaired fatty acid metabolism, transient obstruction of the left ventricular outflow, and catecholamine-mediated myocardial dysfunction has each been proposed as potential mechanism. [2-5] The optimal management of patients presenting with this syndrome depends mainly on the hemodynamic condition of the patient and remains primarily symptomatic in nature. Nearly 2 decades following the first report of this entity, it has been increasingly recognized. [6] Despite increased awareness, the pathophysiology of the condition remains uncertain, and few reports have suggested a specific mechanism, beyond high catecholamine levels, as a trigger for the syndrome. New variants of this disease, involving a different part of the left ventricular wall, have recently been described in the literature. [7-14] Based on these observations, a new term, "stress cardiomyopathy," is now commonly used in the medical community to describe all varieties of this condition.

What is Stress Cardiomyopathy?

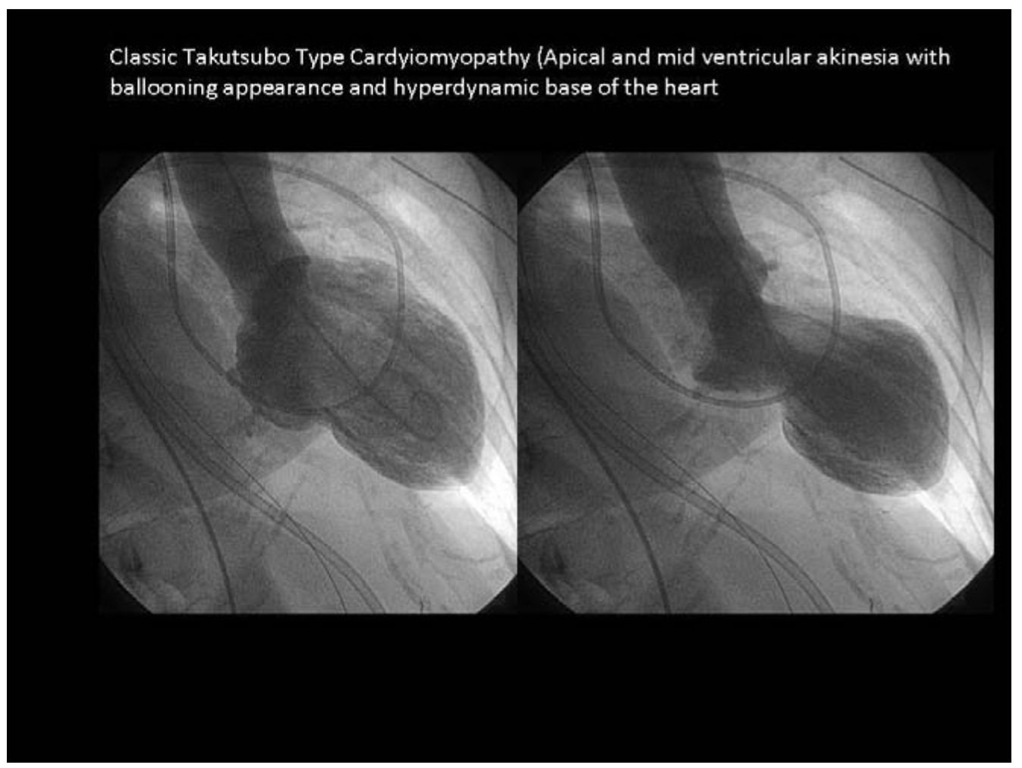

Stress cardiomyopathy is a cardiac syndrome characterized by acute onset of chest pain and completely reversible regional contractile dysfunction (Table 1). On left ventriculography, typical wall motion abnormalities, such as apical and mid-ventricular akinesia and a hypercontractile base, can be identified. (Figure 1) Usually coronary angiography reveals no identifiable epicardial coronary artery disease. (Figure 2) Recently, a few cases of transient ballooning involving the mid-ventricular left ventricle, sparing the apical and basal segments, have also been documented. [9] Stress cardiomyopathy mimics symptoms of acute myocardial infarction with acute chest pain, electrocardiographic (ECG) changes, and a transient increase in blood levels of cardiac biomarkers including troponins although less marked than with acute myocardial infarction. In 1991 Sato and Dote first described this transient contractile dysfunction, naming it tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. [1] Other groups called the syndrome apical "ballooning", "broken heart", "scared to death", "ampulla-syndrome", or "acute stress cardiomyopathy". [3]

Table 1. Symptoms and Stress at the time of presentation

|

Characteristics |

(%) (N = 185) |

|

Symptom |

|

|

Chest Pain |

65.9 (122) |

|

Dyspnea |

16.2 (30) |

|

Syncope |

4.9 (9) |

|

Chest pain and dyspnea |

3.2 (6) |

|

Nausea |

1.6 (3) |

|

ECG changes |

1.6 (3) |

|

CVA |

1.1 (2) |

|

Palpitations |

1.1 (2) |

|

V-fib |

0.5 (1) |

|

Back Pain |

0.5 (1) |

|

Fatigue |

0.5 (1) |

|

Cardiac Arrest |

0.5 (1) |

|

Not Reported |

1.1 (2) |

|

Precipitating Stress |

|

|

Emotional |

47.9 (80) |

|

Physical |

29.3 (49) |

|

None |

22.8 (38) |

The characteristic clinical syndrome of stress cardiomyopathy is acute left ventricular dysfunction, following a sudden emotional or physical stress. Patients typically present with chest pain similar to that of acute myocardial infarction (central, heavy, squeezing and crushing). On occasion, the discomfort radiates to the arms causing anxiety (Table 1). The pain can also mimic acute pericarditis, pulmonary embolism, acute aortic dissection and costochondritis. Although the coronary arteries have no flow-limiting lesions, acute changes on the ECG suggesting ischemia, and raised levels of cardiac enzymes, reflecting acute myocardial injury, are usually present. Left ventricular dysfunction and wall-motion abnormalities are typically seen, affecting the apical and, frequently, the midventricular left ventricular myocardium, but sparing the basal myocardium. On left ventriculography, echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), these functional abnormalities typically resemble a flask with a short, narrow neck and wide, rounded body. The shape of the ventricle at end systole resembles the Japanese fisherman’s octopus pot—the tako-tsubo—from which the syndrome derives its original name. The hypercontractile basal myocardium can generate left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in the presence of apical and midwall hypokinesis. The final element of the syndrome is that left ventricular function and apical wall motion return to normal within days or weeks of the acute insult, in a similar manner to traditional myocardial stunning. Right ventricular involvement appears to be less common but has been reported in the literature. [15,16] Apical distribution of the right ventricular wall akinesia suggests that for some unknown reason, apical ballooning syndrome affects the heart in a geometrical way involving mostly the apex and the mid left ventricular walls and does not follow a single coronary territory. [8] Some studies have found decreased flow in the apical left ventricular wall compared with the base, which could partially explain this geometrical involvement. [16,17]

Figure 1. Classic Takutsubo Type Cardyiomyopathy (Apical and mid ventricular akinesia with ballooning appearance and hyperdynamic base of the heart

Figure 2. Takutsubo Type Cardyiomyopathy with normal coronaries on angiogram

Etiology

The cause of stress cardiomyopathy is unknown. However, all available evidence is consistent with the concept that this disease results from extreme emotional and/or physical stress. The disease shows a strong predominance for postmenopausal women. (Table 2) The seemingly increased susceptibility of women to stress-related left ventricular dysfunction and potential gender-related differences in response to catecholamines is not well understood.5 However, sex hormones exert important influences on the sympathetic neurohumoral axis as well as on coronary vasoreactivity. The mechanisms underlying stress cardiomyopathy are unclear with exaggerated sympathetic stimulation probably being central to its causation. Thus, catecholamine excess has been implicated but not well documented.

Table 2. Patient characteristics

|

Characteristics Mean age (years) |

(%) (N = 185) 67.7 |

|

Female |

93.5 (173) |

|

Male |

6.5 (12) |

|

Race |

|

|

Asian |

57.2 (83) |

|

White |

40 (58) |

|

Other |

2.8 (4) |

|

Not reported |

21.5 (40) |

One hypothesis is that these patients experience myocardial ischemia as a result of epicardial coronary arterial spasm, secondary to increased sympathetic tone leading to vasoconstriction despite the absence of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. [18] Another possible mechanism of direct myocardial injury is catecholamine-mediated myocardial stunning. Supporting this hypothesis is the well known fact that adrenoceptor density is higher in the cardiac apex compared with other areas of the myocardium. This might account for myocardial dysfunction and apical ballooning during catecholamine stress. [5] The elevated catecholamines can produce a concentration dependent decrease in myocyte viability, as demonstrated by a significant release of creatine kinase from the affected cells leading to decreased viability due to cyclic AMP-mediated calcium overload. [19] Abnormal coronary flow in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease has recently been reported in patients with stress-related myocardial dysfunction. [17] Further correlations between this cardiomyopathy and specific genetic profiles are not known at this time. It has been hypothesized that stress cardiomyopathy is a form of myocardial stunning, but with a different cellular mechanisms than is seen during transient episodes of ischemia secondary to coronary stenosis.

Patients with stress cardiomyopathy usually have supra-physiological levels of plasma catecholamines and stress-related neuropeptides. Unlike polymorphonuclear inflammation seen with infarction, in stress cardiomyopathy there is contraction band necrosis, a unique form of myocyte injury characterized by hypercontracted sarcomeres, dense eosinophilic transverse bands, and an interstitial mononuclear inflammatory response. Endomyocardial biopsy has demonstrated the presence of contraction band necrosis in patients with stress cardiomyopathy. [5] Contraction band necrosis is a type of cell death identified as early as 2 minutes after cell injury has occurred and can cause release of cardiac biomarkers. [20] Focal myocarditis and contraction band necrosis has been found in states of excess circulating catecholamine such as pheochromocytoma,21 subarachnoid haemorrhage, [22,23] eclampsia [23] and fatal asthma. [24] Contraction band necrosis has also been documented in autopsies of patients with normal coronary vessels who suffered from coronary spasm due to various causes. [23,25] These findings all suggest that catecholamines may be a link between emotional stress and cardiac injury.