Introduction

Emergency physicians in the United States treat in excess of 250 000 gunshot wounds per year. More than 90% of these wounds are the result of projectiles discharged from handguns. Historically, emergency physicians have been trained to treat gunshot wound injuries without consideration for the forensic issues associated with them. As a consequence, emergency department personnel have misinterpreted wounds, have inadvertently altered their physical characteristics, and destroyed critical forensic evidence associated with the wounds in the process of rendering patient care. These problems are avoidable. Emergency room personnel should have the tools and knowledge base necessary to determine the following forensic issues: range of fire of the offending weapon (projectile) and entrance wound versus exit.

Misdiagnosis and Errors of Interpretation

The majority of gunshot wound misinterpretations result from the fallacious assumption that the exit wound is always larger than the entrance wound. The size of any gunshot wound, entrance or exit, is primarily determined by five variables: the size, shape, configuration and velocity of the bullet at the instant of its impact with the tissue and the physical characteristics of the impacted tissue itself. When the exiting projectile has substantial velocity or has fragmented, or changed its configuration, the exit wound it generates may in fact be larger than the entrance wound associated with it. Conversely, if the velocity of the exiting projectile is low, the wound it leaves behind may be equal to or smaller than its corresponding entrance wound. If the kinetic energy of the bullet is transferred to underlying skeletal tissue, bone fragments may be extruded from the exit wound, contributing to the size and shape of the wound. The elasticity of the overlying connective tissue and skin can also affect wound size. Misinterpretations of gunshot wounds by nonforensically trained physicians have ranged as high as 79%. To avoid the misinterpretation of wounds, health practitioners who lack forensic training should limit their documentation of the wounds to detailed descriptions of their appearance and not attempt to make the determination: ‘entrance or exit’.

Entrance Wounds

Entrance wounds can be divided into four general categories, dictated by the range of fire from which the bullet was discharged. Range of fire is an expression used to describe the distance between the gun’s muzzle and the victim/patient. The different ranges of fire are: distant or indeterminate range; intermediate or medium range; close range and contact. The entrance wounds associated with each of the four ranges of fire categories will have physical characteristics pathognomonic to each category.

Distant or indeterminate entrance wounds

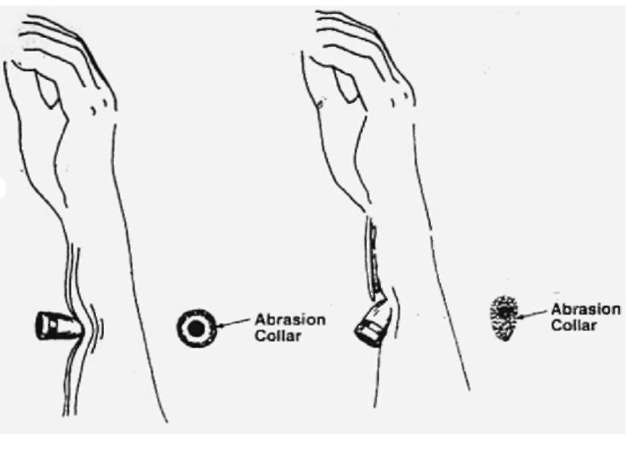

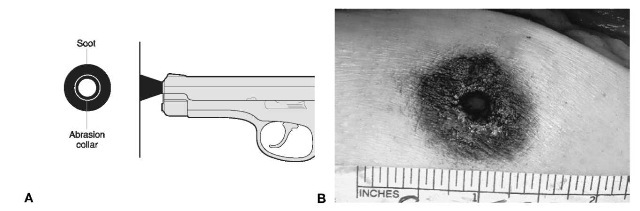

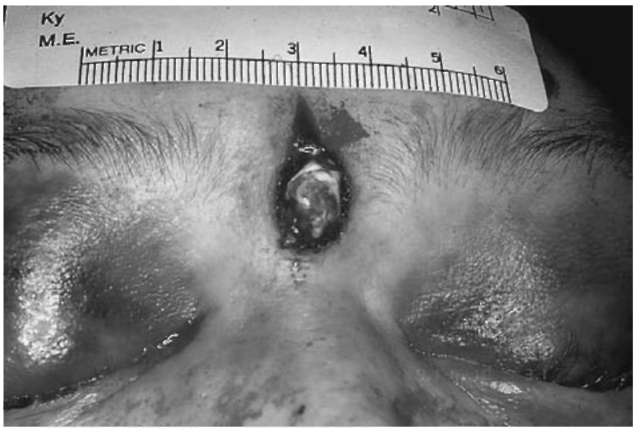

The distant or indeterminate gunshot wound of entrance is one which results when the weapon is discharged at such a distance that only the bullet makes contact with the victim’s skin. When the bullet or projectile penetrates the epithelial tissue, there is friction between the skin and the projectile. This friction results in an abraded area of tissue which surrounds the entry wound and is know as an abrasion collar (Figs 1 and 2). In general, with the exception of gunshot wounds on the soles of the feet and palms of the hands, all handgun gunshot wounds of entrance will have an associated abrasion collar. The width of the abrasion collar will vary depending on the caliber of the weapon, the angle of bullet impact and the anatomical site of entrance. Skin which overlies bone will generally have a narrower abrasion collar than skin supported by soft tissue. Entrance wounds on the soles and palms are usually slit-like in appearance. It is important to note that the abrasion collar is not the result of thermal changes associated with a ‘hot projectile’. The terms abrasion margin, abrasion rim, abrasion ring and abrasion collar are all used interchangeably.

Figure 1 An abrasion collar is the abraided area of tissue surrounding the entrance wound created by the bullet when it dents and passes through the epithelium. The abrasion collar will vary with the angle of impact.

Figure 2 The area of abraided tissue surrounding this gunshot wound of entrance is the ‘abrasion collar’. Additional appropriate terms would include: abrasion margin, abrasion rim or abrasion ring.

Intermediate range entrance wounds

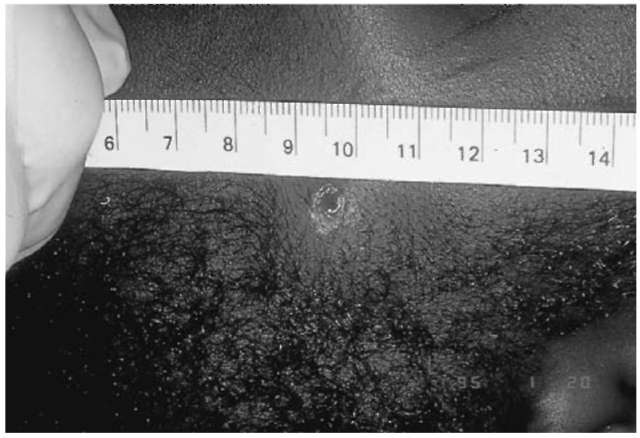

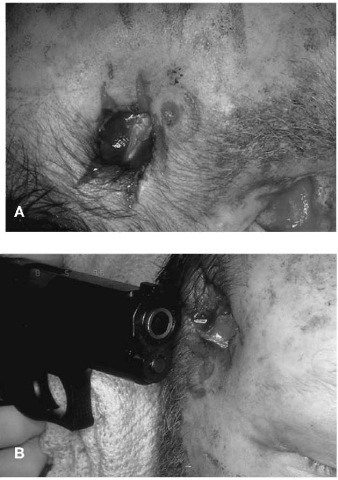

‘Tattooing’ is pathognomonic for an intermediate range gunshot wound. Tattooing is a term used to describe the punctate abrasions observed when epithelial tissue comes into contact with partially burned or unburned grains of gunpowder. These punctate abrasions cannot be wiped away and will remain visible on the skin for several days. Clothing, hair or other intermediate barriers may prevent the powder grains from making contact with the skin. Though it has been reported, it is rare for tattooing to occur on the palms of the hands or soles of the feet, because of the thickness of the epithelium in these areas.

The density of the tattooing will be dictated by: the length of the gun’s barrel, the muzzle-to-skin distance, the type and amount of gunpowder used and the presence of intermediate objects. Punctate abrasions from unburned gunpowder have been reported with distances as close as 1 cm, and as far away as 100 cm (Fig 3A, B).

Figures 3 A, B ‘Tattooing’ is the term used to describe punctate abrasions from the impacting of unburned grains of gunpowder on epithelial tissue. Tattooinghas been recorded with distances as close as 1 cm and as far away as 100 cm. The density of the tattooing will be principally determined by the muzzle to skin distance but may also be affected by the length of the gun barrel and the type of gun powder used.

Close Range Wounds

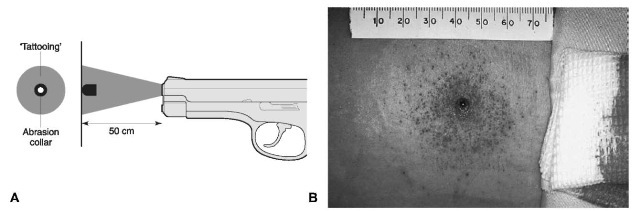

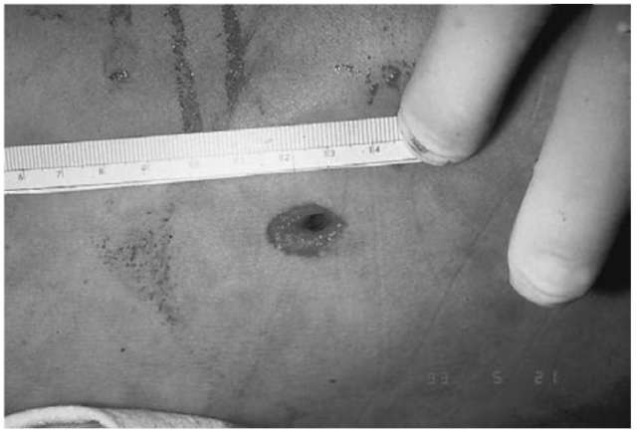

Close range entrance wounds are usually characterized by the presence of a surface contaminant known as soot (Fig. 4A and Fig. 4B). Soot is the carbonaceous byproduct of combusted gunpowder and vaporized metals. It is generally associated with a range of fire of less than 10 cm, but has been reported in wounds inflicted at distances of up to 20-30 cm. The density of the soot will decrease as the muzzle-to-skin distance decreases. The concentration of soot is also influenced by the amount and type of gunpowder used, the gun’s barrel length, the caliber of the ammunition and the type of weapon used. For close range wounds, the longer the barrel length, the denser the pattern at a given distance. At a close range of fire, the visibility of tattooing may be obscured by the presence of soot. Also, at a close range, the unburned grains of powder may be injected directly into the entrance wound.

The term ‘powder burns’ is one used to describe a thermal injury to the skin, associated exclusively with the rise of weapons (muzzle loaders and starter pistols). When black power ignites, it produces a flame and large amounts of white smoke. The flame sometimes catches the user’s clothing on fire, resulting in powder burns. Black powder is not used in any commercially available ammunition today. The expression powder burns should not be used to describe the carbonaceous material deposited on the skin with entrance wounds inflicted by commercially available cartridges.

Contact wounds

Contact wounds are wounds which occur when the barrel of the gun is in actual contact with the clothing or skin of the victim. There are two types of contact wounds: loose contact and tight. Tight contact wounds occur when the muzzle is pressed tightly against the skin. All material that is discharged from the barrel, including soot, gases, incompletely burned gunpowder, metal fragments, and the projectile are injected into the wound. In a loose contact wound, the contact between the skin and the muzzle is incomplete, and soot and other residues will be distributed along the surface of the epithelium.

Figure 4 A, B Close range gunshot wounds are characterized by the presence of soot. Soot is a carbonaceous material which will deposit on skin or clothingat distances generally less than 10cm.

When a tight contact wound occurs in an area of thin tissue or tissue overlying bone, the hot gases of combustion will cause the skin to burn, expand and rip (Fig. 5). The tears of the skin will appear triangular or stellate in configuration (Fig. 5). These stellate tears are commonly misinterpreted as exit wounds when the physician is basing that opinion on the size of the wound alone. The stellate wounds resulting from contact with the barrel will always be associated with the presence of seared skin and soot (Fig. 6). The stellate tears of exit wounds will lack soot and seared skin. The charred or seared skin of contact wounds will have the microscopic characteristics of thermally damaged skin. The injection of gases into the skin may also cause the skin to be forcibly compressed against the barrel of the gun and may leave a muzzle contusion or muzzle abrasion surrounding the wound (Fig. 7A, and B).

The size of gunshot wounds of entrance bears no reproducible relationship to the caliber of the projectile.

Exit Wounds

Exit wounds will assume a variety of shapes and configurations and are not consistently larger than their corresponding entrance wounds. The exit wound size is dictated primarily by three variables: the amount of energy possessed by the bullet as it exits the skin, the bullet size and configuration, and the amount of energy transferred to underlying tissue,i.e. bone fragments. Exit wounds usually have irregular margins and will lack the hallmarks of entrance wounds, abrasion collars, soot, and tattooing (Fig. 8A and B). If the skin of the victim is pressed against or supported by a firm object, as the projectile exits, the wound may exhibit an asymmetric area of abrasion.

Figure 5 The contact wound will exhibit triangular shaped tears of the skin. These stellate tears are the result of injection of hot gases beneath the skin. These gases will cause the skin to rip and tear in this characteristic fashion.

Figure 6 Contact wounds will also exhibit seared wound margins as well as stellate-shaped tears. This is a contact wound from a 38 caliber revolver.

Figure 7 A, B The injection of gases into the skin will cause the skin to expand and make forceful contact with the barrel of the gun (A). If there is sufficient gas, this contact will leave a ‘muzzle contusion’ or ‘muzzle abrasion’ around the wound. This pattern injury mirrors the end of the barrel (B).

Figures 8 A, B Gunshot wounds of exit generally have irregular wound margins and will lack the physical evidence associated with entrance wound includingabrasion collars, soot, seared skin and ‘tattooing’. Exit wounds associated with handgun ammunition are not consistently larger than the associated exit wound. These slit-like exit wounds have irregular margins.

This area of abrasion has been described as a ‘false’ abrasion collar and is termed a ‘shored’ exit wound (Fig. 9). This false abrasion collar results when the epithelium is forced outward and makes contact or is slapped against the supporting structure. Examples of supporting structures are chair backs, floors, walls, or tight clothing. The shored exit wound may also be called a ‘supported’ exit wound.

Figure 9 A ‘shored’ exit wound has the appearance of a ‘false’ abrasion collar. This false abrasion collar results when epithelium is forced outward and makes contact or is slapped against a supporting structure, i.e. floor, wall or furniture. A short exit may also be referred as a supported exit wound.

Evidence Collection

Any tissue excised from a gunshot wound margin should be submitted for microscopic evaluation. This microscopic examination will reveal the presence of carbonaceous materials, compressed and distorted epithelial cells and thermally induced collagenous changes in the dermal layer. This information may assist the practitioner in determining the range of fire or entrance versus exit when the physical exam is indeterminate. It is imperative that treating physicians recognize the importance of preserving evidence in the gunshot wound victim. It has been recognized that victims of gunshot wounds should undergo some degree of forensic evaluation prior to surgical intervention. It is also necessary that healthcare practitioners recognize, preserve and collect short-lived evidence and not contaminate or destroy evidence while rendering care.

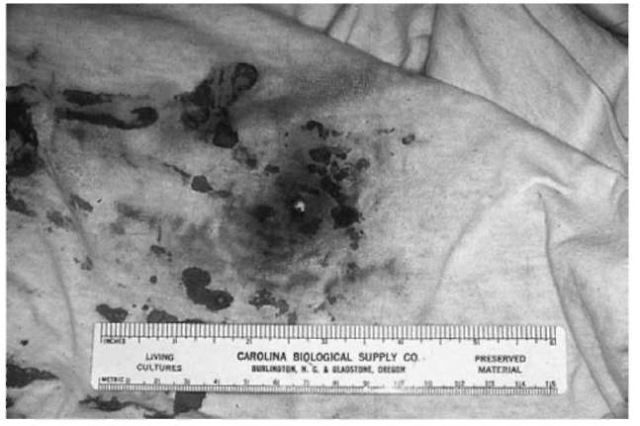

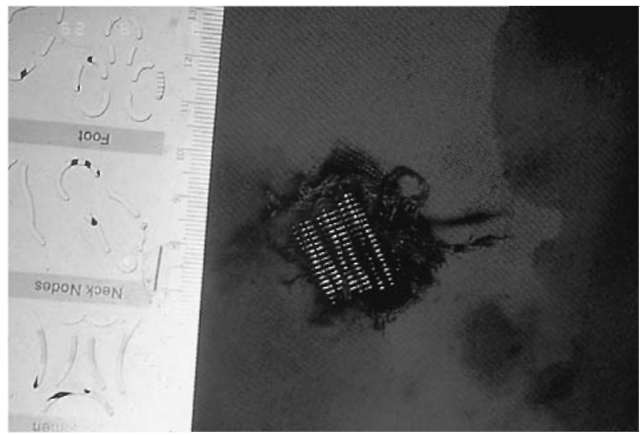

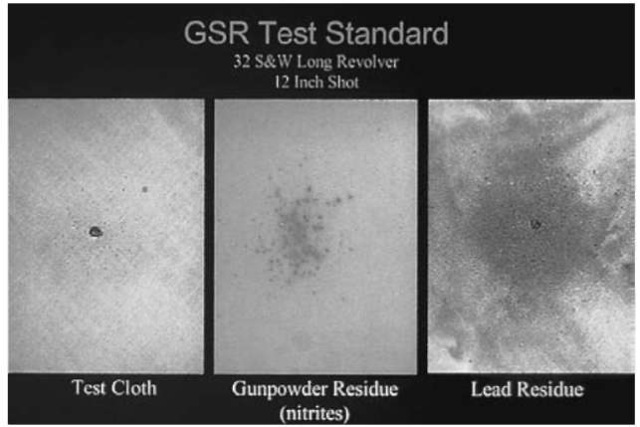

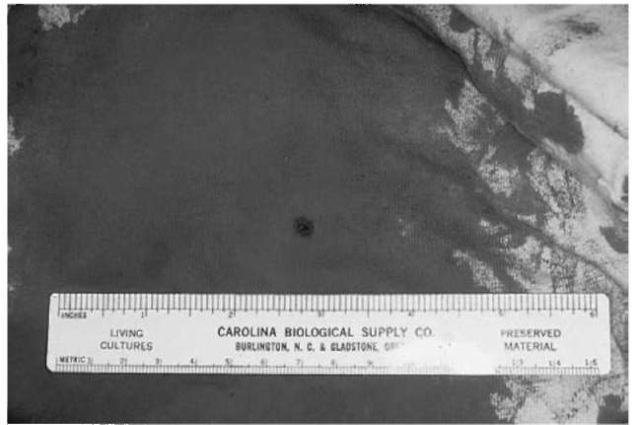

The clothing of a gunshot wound victim may yield valuable information about the range of fire and will aid physicians in their efforts to distinguish entrance from exit wounds (Fig. 10). Fibers of clothing will deform in the direction of the passing projectile (Fig. 11). Gunpowder residues and carbonaceous soot will deposit on clothing, just as they do on skin. Some of these residues are not visible to the naked eye and require standard forensic laboratory staining techniques to detect the presence of lead and nitrates (Fig. 12). Some bullets, in particular lead bullets, may deposit a thin layer of lead residue on clothing as they penetrate; this residue is termed ‘bullet wipe’ (Fig. 13).

Figure 10 Carbonaceous material as well as gunshot residue may be deposited on victims’ clothingif the handgun is discharged within range of fire of less then 1 m. Some gunshot residue from nitrates and vaporized lead will be invisible to the naked eye. All clothing should be collected and placed in separate paper containers for evaluation by the forensic laboratory.

Figure 11 Close examination of fibers may reveal the direction of the passing projectile.

When collecting articles of clothing from a gunshot wound victim, each article must be placed in a separate paper bag in order to avoid crosscontamination.

Some jurisdictions may elect to perform a gunshot residue test to determine the presence of invisible residues on a suspects’ skin. Residues from the primer, including barium nitrate, antimony sulfide, and lead peroxide may be deposited on the hands of the individual who fired the weapon. The two methods used to evaluate for residues are flameless atomic absorption spectral photometry (FAAS), and scanning microscope-energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (SEM-EDX). For analysis by FAAS, a specimen is collected by swabbing the ventral and dorsal surfaces of the hand with a 5% nitric acid solution. For analysis by SEM-EDX, tape is systematically pressed against the skin and packaged. A second method involves placement of tape on the hands and examining the material under a scanning electron microscope. The specificity and sensitivity of these tests have been questioned, as residues may be spread about the crime scene. These residues may be spread by secondary contact with a weapon or furniture items, and have been known to result in false positive tests. Controlled studies involving the transfer of gunshot residues from individuals who fired a weapon to suspects being handcuffed, have been documented. If a gunshot residue test is to be performed on a victim, it should be done within the first hour of the weapon’s discharge to increase the sensitivity of the test.

Figure 12 The forensic laboratory can use tests to detect the presence of vaporized lead and nitrates. These tests will assist the forensic investigator in determining the range of fire.

Figure 13 A lead or well-lubricated projectile may leave a ring of lead or lubricant on clothingas it passes through. This deposition of lubricant or lead is referred to as ‘bullet wipe’.

The bullet, the bullet jacket and the cartridge are invaluable pieces of forensic evidence. The forensic firearms examiner may use these items to identify or eliminate a weapon as the one which was fired. When these items are collected from the living patient, they should be packaged in a breathable container, a container that allows a free exchange of outside air. If such an item were placed in a closed plastic container, mold may form and evidence degrade.

When handling evidence, all metal-to-metal contact should be avoided. The tips of hemostats should be wrapped in sterile gauze and all evidence placed immediately in containers for transport (skip the metal basin step). Metal-to-metal contact may destroy or obliterate critical microscopic marks.

Estimation of Bullet Caliber Using Radiographs

Radiographs taken to assist the treating physician in locating retained projectiles may also be of evidentiary value. Radiographs will assist the physician in determining the direction from which projectiles were fired as well as their simple number. Practitioners should not render opinions as to the caliber of a specific projectile, based upon radiographic imaging alone, because only radiographs taken exactly 72 in (183 cm) from the projectile will reveal the projectile’s appropriate size. The bullet size on the radio-graphic film will increase as the distance between the film and X-ray source decreases.

Conclusion

If investigators and health practitioners receive adequate forensic training, the distinction of entrance from exit wounds will not be difficult. When practitioners are unsure, they should refrain from placing statements regarding entrance and exit in the medical record. The physician and patient would be better served if the wound were measured, photographed and accurately described, using appropriate forensic terminology and sample tissues sent to the forensic pathologist for microscopic analysis. Of course, the primary concern of all practitioners caring for survivors of gunshot wounds is the health and well-being of their patient; however, a simple awareness of and attention to the forensic issues involved in gunshot wound examination and management can profoundly affect the medicolegal/justice aspects of the victim’s experience.