FACTOR

1. The basis on which a shipping charge is based such as a rate per mile the cargo is transported.

2. A firm that buys accounts receivable from exporters using short-term maturities of no longer than a year and then assumes responsibility for collecting the receivables. This usually involves no recourse, which means the factor must bear the risk of collection. Some banks and commercial finance companies factor (buy) accounts receivable. The purchase is made at a discount from the account’s value. Customers remit either directly to the factor (notification basis) or indirectly through the seller.

FACTORING

Discounting without recourse an account receivable by an intermediate company called a factor. The exporter receives immediate (discounted) payment, and the factor receives eventual payment from the importer.

FADE-OUT

Fade-out is a host government policy toward foreign direct investment (FDI) that calls for progressive divestment of foreign ownership over time, ending with either complete local ownership or limited foreign ownership share. For example, a joint venture may have served the goal of helping a firm acquire local experience in the initial entry state but no longer serves this need at a later stage.

FAIR VALUE

1. The theoretical value of a security based on current market conditions. The fair value is such that no arbitrage opportunities exist.

2. Price negotiated at arm’s-length between a willing buyer and a willing seller, each acting in his or her own best interest.

3. The fair market value of a multinational company’s activities that is used as a basis to determine tax.

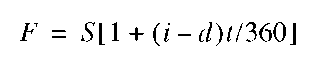

4. The “proper” value of the spread between the Standard & Poor’s 500 futures and the actual S&P Index that makes no economic difference to investors whether they own the futures or the actual stocks that make up the S&P 500. Their buy and sell decisions will be driven by other factors. Through a complex formula using current short-term interest rates and the amount of time left until the futures contract expires, one can determine what the spread between the S&P futures and the cash “should be.” The formula for determining the fair value

where F = break-even futures price, S = spot index price, i = interest rate (expressed as a money-market yield), d = dividend rate (expressed as a money-market yield), and t = number of days from today’s spot value date to the value date of the futures contract.

FIAT MONEY

Fiat money is nonconvertible paper money backed only by full faith that the monetary authorities will not cheat (by issuing more money).

FINANCE DIRECTOR

The finance director is the financial executive responsible for the finance function of the company. The finance director may be a controller, treasurer, or Chief Financial Officer (CFO). A group finance director of an MNC typically reports to the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and the member of the main board of directors with responsibility for leading the finance function and contributing actively to the overall strategy and development of the business. This involves a blend of hands-on operational involvement and high level influencing/negotiating with banks, venture capitals, and strategic alliance partners/suppliers.

FINANCIAL DERIVATIVE

A transaction, or contract, whose value depends on or, as the name implies, derives from the value of underlying assets such as stocks, bonds, mortgages, market indexes, or foreign currencies. One party with exposure to unwanted risk can pass some or all of that risk to a second party. The first party can assume a different risk from the second party, pay the second party to assume the risk, or, as is often the case, create a combination. The participants in derivatives activity can be divided into two broad types—dealers and end-users. Dealers include investment banks, commercial banks, merchant banks, and independent brokers. In contrast, the number of end-users is large and growing as more organizations are involved in international financial transactions. End-users include businesses; banks; securities firms; insurance companies; governmental units at the local, state, and federal levels; “supernational” organizations such as the World Bank; mutual funds; and both private and public pension funds. The objectives of end-users may vary. A common reason to use derivatives is so that the risk of financial operations can be controlled. Derivatives can be used to manage foreign exchange exposure, especially unfavorable exchange rate movements. Speculators and arbitrageurs can seek profits from general price changes or simultaneous price differences in different markets, respectively. Others use derivatives to hedge their position; that is, to set up two financial assets so that any unfavorable price movement in one asset is offset by favorable price movement in the other asset. There are five common types of derivatives: options, futures, forward contracts, swaps, and hybrids. The general characteristics of each are summarized in Exhibit 40. An important feature of derivatives is that the types of risk are not unique to derivatives and can be found in many other financial activities. The risks for derivatives are especially difficult to manage for two principal reasons: (1) the derivative products are complex, and (2) there are very real difficulties in measuring the risks associated derivatives.

It is imperative for financial officers of a firm to know how to manage the risks from the use of derivatives. Exhibit 40 compares major types of financial derivatives.

EXHIBIT 40

General Characteristics of Major Types of Financial Derivatives

| Type | Market | Contract | Definition |

| Option | OTC or | Custom* | Gives the buyer the right but not the obligation to buy or sell |

| Organized | or | a specific amount at a specified price within a specified | |

| Exchange | Standard | period | |

| Futures | Organized | Standard | Obligates the holder to buy or sell at a specified price on a |

| Exchange | specified date | ||

| Forward | OTC | Custom | Same as futures |

| Swap | OTC | Custom | Agreement between the parties to make periodic payments to |

| each other during the swap period | |||

| Hybrid | OTC | Custom | Incorporates various provisions of other types of derivatives |

* Custom contracts vary and are negotiated between the parties with respect to their value, period, and other terms.

FINANCIAL FUTURES

Financial futures are types of futures contracts in which the underlying commodities are financial assets. Examples are debt securities, foreign currencies, and market baskets of common stocks.

FINANCIAL MARKETS

The financial markets are composed of money markets and capital markets. Money markets, also called credit markets, are the markets for debt securities that mature in the short term (usually less than one year). Examples of money-market securities include U.S. Treasury bills, government agency securities, bankers’ acceptances, commercial paper, and negotiable certificates of deposit issued by government, business, and financial institutions. The money-market securities are characterized by their highly liquid nature and a relatively low default risk. Capital markets are the markets in which long-term securities issued by the government and corporations are traded. Unlike the money market, both debt instruments (bonds) and equity share (common and preferred stocks) are traded. Relative to money-market instruments, those of the capital market often carry greater default and market risks but return a relatively high yield in compensation for the higher risks. The New York Stock Exchange, which handles the stock of many of the larger corporations, is a prime example of a capital market. The American Stock Exchange and the regional stock exchanges are yet another example. These exchanges are organized markets. In addition, securities are traded through the thousands of brokers and dealers on the over-the-counter (or unlisted) market, a term used to denote an informal system of telephone contacts among brokers and dealers. There are other markets including (1) the foreign exchange market, which involves international financial transactions between the U.S. and other countries; (2) the commodity markets which handle various commodity futures; (3) the mortgage market that handles various home loans; and (4) the insurance, shipping, and other markets handling short-term credit accommodations in their operations. A primary market refers to the market for new issues, while a secondary market is a market in which previously issued, “secondhand” securities are exchanged. The New York Stock Exchange is an example of a secondary market.

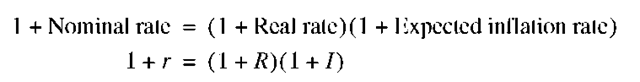

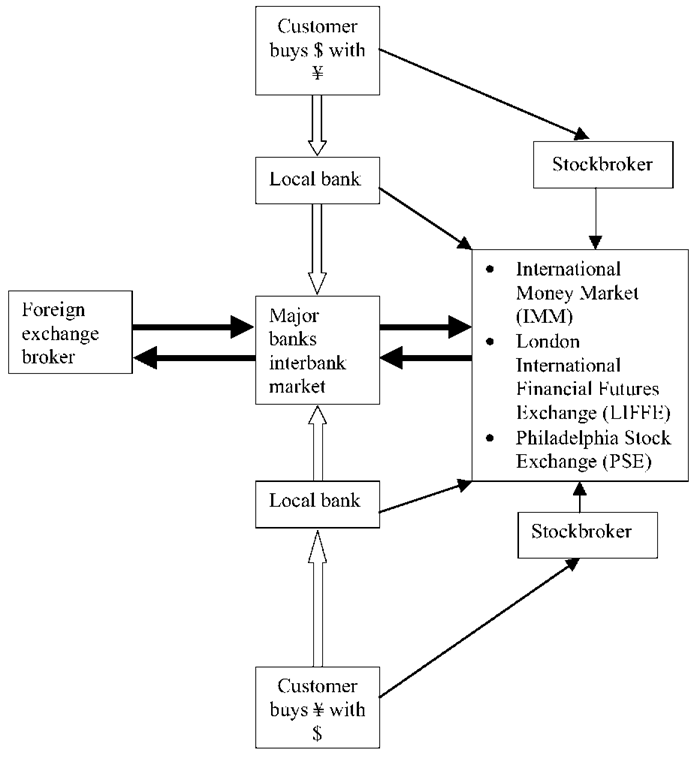

FISHER EFFECT

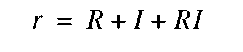

The Fisher effect, named after Irving Fisher, states that that nominal interest rates (r) in each country equal the required real rate of return (R) plus a premium for expected inflation (I) over the period of time for which the funds are to be lent (i.e., r = R + I). To be precise,

or

which is approximated as r = R + I. The theory implies that countries with higher rates of inflation have higher interest rates than countries with lower rates of inflation. Note: The equation requires a forecast of the future rate of inflation, not what inflation has been.

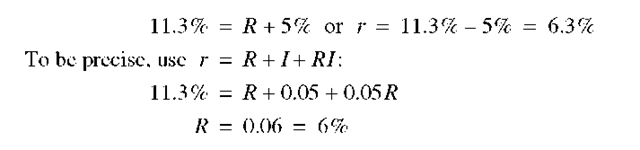

EXAMPLE 47

If you have $100 today and loan it to your friend for a year at a nominal rate of interest of 11.3%, you will be paid $111.30 in one year. But if during the year inflation (prices of goods and services) goes up by 5%, it will take $105 at year end to buy the same goods and services that $100 purchased at the start of the year. Then the increase in your purchasing power over the year can be quickly found by using the approximation r = R + I:

If you have $100 today and loan it to your friend for a year at a nominal rate of interest of 11.3%, you will be paid $111.30 in one year. But if during the year inflation (prices of goods and services) goes up by 5%, it will take $105 at year end to buy the same goods and services that $100 purchased at the start of the year. Then the increase in your purchasing power over the year can be quickly found by using the approximation r = R + I:

In other words, at the new higher prices, your purchasing power will have increased by only 6%, although you have $11.30 more than you had at the beginning of the year. To see why, suppose that at the start of the year, one unit of the market basket of goods and services cost $1, so you could buy 100 units with your $100. At year-end, you have $11.30 more, but each unit now costs $1.05 (with the 5% rate of inflation). This means that you can purchase only 106 units ($111.30/$1.05), representing a 6% increase in real purchasing power.

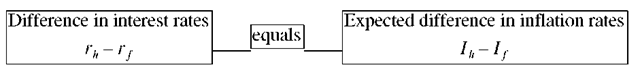

The generalized version of the Fisher effect claims that real returns are equalized across countries through arbitrage—that is, rh and rf where the subscripts h and f are home and foreign real rates. If expected real returns were higher in one country than another, capital would flow from the second to the first currency. This process of arbitrage would continue, in the absence of government intervention, until expected real returns were equalized. In equilibrium, then, with no government interference, it should follow that nominal interest rate differential will approximately equal the anticipated inflation rate differential, or

where rh and rf are the nominal home and foreign currency interest rates, respectively. If these rates are relatively small, then this exact relationship can be approximated by

Note: Equation 1 can be converted into Equation 2 by subtracting 1 from both sides and assuming that rh and rf are relatively small. This generalized version of the Fisher effect says that currencies with high rates of inflation should bear higher interest rates than currencies with lower rates of inflation.

EXAMPLE 48

If inflation rates in the United States and the United Kingdom are 4% and 7%, respectively, the Fisher effect says that nominal interest rates should be about 3% higher in the United Kingdom than in the United States.

A graph of Equation 2 is shown in Exhibit 41. The horizontal axis shows the expected difference in inflation rates between the home country and the foreign country, and the vertical axis shows the interest differential between the two countries for the same time period. The parity line shows all points for which rh — rf = Ih — If. Point A, for example, is a position of equilibrium, as the 2% higher rate of inflation in the foreign country (rh — rf = —2%) is just offset by the 2% lower home currency interest rate (Ih — If = —2%). At point B, however, where the real rate of return in the home country is 1% higher than in the foreign country (an inflation differential of 3% versus an interest differential of only 2%), funds should flow from the foreign country to the home country to take advantage of the real differential. This flow will continue until expected real returns are equal.

EXHIBIT 41

The Fisher Effect

FIXED EXCHANGE RATES

An international financial arrangement under which the values of currencies in terms of other currencies are fixed by the governments involved and by governmental intervention in the foreign exchange markets.

FLOATING EXCHANGE RATES

Also called flexible exchange rates, floating exchange rates are a system in which the values of currencies in terms of other currencies are determined by the supply of and demand for the currencies in foreign exchange markets. Arrangements may vary from free float, i.e., absolutely no government intervention, to managed float, i.e., limited but sometimes aggressive government intervention, in the foreign exchange market.

FOREIGN BOND

A foreign bond is a bond issued by a foreign borrower on a foreign capital market just like any domestic (local) firm. The bond must of course be denominated in a local currency—the currency of the country in which the issue is sold. The terms must conform to local custom and regulations. A foreign bond is the simplest way for an MNC to raise long-term debt for its foreign expansion. A bond issued by a German corporation, denominated in dollars, and sold in the U.S. in accordance with SEC and applicable state regulations, to U.S. investors by U.S. investment bankers, would be a foreign bond. Except for the foreign origin of the borrower, this bond will be no different from those issued by equivalent U.S. corporations. Foreign bonds have nicknames: foreign bonds sold in the U.S. are Yankee bonds, foreign bonds sold in Japan are Samurai bonds, and foreign bonds sold in the United Kingdom are Bulldogs. Exhibit 42 below specifically reclassifies foreign bonds from a U.S. investor’s perspective.

EXHIBIT 42

Foreign Bonds to U.S. Investors

| Sales | ||

| Issuer | In the U.S. | In Foreign Countries |

| Domestic | Domestic bonds | Eurobonds |

| Foreign | Yankee bonds | Foreign bonds |

| Eurobonds |

FOREIGN BOND MARKET

The foreign bond market is the market for long-term loans to be raised by MNCs for their foreign expansion. It is that portion of the domestic market for bond issues floated by foreign companies or governments. In contrast, the Eurobond market is an international market for long-term debt.

FOREIGN BRANCHES

A foreign branch is a legal and operational part of the parent bank. Creditors of the branch have full legal claims on the bank’s assets as a whole and, in turn, creditors of the parent bank have claims on its branches’ assets. Deposits of both foreign branches and domestic branches are considered total deposits of the bank, and reserve requirements are tied to these total deposits. Foreign branches are subject to two sets of banking regulations. First, as part of the parent bank, they are subject to all legal limitations that exist for U.S. banks. Second, they are subject to the regulation of the host country. Domestically, the OCC is the overseas regulator and examiner of national banks, whereas state banking authorities and the Federal Reserve Board share the authority for state-chartered member banks. Granting power to open a branch overseas resides with the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. As a practical matter, the Federal Reserve System and the OCC dominate the regulation of foreign branches. The attitudes of host countries toward establishing and regulating branches of U.S. banks vary widely.

Typically, countries that need capital and expertise in lending and investment welcome the establishment of U.S. bank branches and allow them to operate freely within their borders. Other countries allow the establishment of U.S. bank branches but limit their activities relative to domestic banks because of competitive factors. Some foreign governments may fear that branches of large U.S. banks might hamper the growth of their country’s domestic banking industry. As a result, growing nationalism and a desire for locally controlled credit have slowed the expansion of American banks abroad in recent years. The major advantage of foreign branches is a worldwide name identification with the parent bank. Customers of the foreign branch have access to the full range of services of the parent bank, and the value of these services is based on the worldwide value of the client relationship rather than only the local office relationship. Furthermore, deposits are more secure, having their ultimate claim against the much larger parent bank and not merely the local office. Similarly, legal loan limits are a function of the size of the parent bank and not of the branch. The major disadvantages of foreign branches are the cost of establishing them and the legal limits placed on the activities in which they may engage.

FOREIGN CREDIT INSURANCE ASSOCIATION

The Foreign Credit Insurance Association (FCIA) is a private U.S. insurance association that insures exporters in conjunction with the Eximbank. It offers a broad range of short-term and medium-term insurance policies to protect losses from political and commercial risks. For providing the insurance, the FCIA charges premiums based on the types of buyers and countries and the terms of payment.

FOREIGN CURRENCY FUTURES

A futures contract promises to deliver a specified amount of foreign currency by some given future date. Foreign currency futures differ from forward contracts in a number of significant ways, although both are used for trading, hedging, and speculative purposes. Participants include MNCs with assets and liabilities denominated in foreign currency, exporters and importers, speculators, and banks. Foreign currency futures are contracts for future delivery of a specific quantity of a given currency, with the exchange rate fixed at the time the contract is entered. Futures contracts are similar to forward contracts except that they are traded on organized futures exchanges and the gains and losses on the contracts are settled each day.

Like forward contracts, a foreign currency futures contract is an agreement calling for future delivery of a standard amount of foreign exchange at a fixed time, place, and price. It is similar to futures contracts that exist for commodities (e.g., hogs, cattle, lumber), for interest-bearing deposits, and for gold. Unlike forward contracts, futures are traded on organized exchanges with specific rules about the terms of the contracts and with an active secondary market.

A. Futures Markets

In the United States the most important marketplace for foreign currency futures is the International Monetary Market (IMM) of Chicago, organized in 1972 as a division of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Since 1985, contracts traded on the IMM have been interchangeable with those traded on the Singapore International Monetary Exchange (SIMEX).

Most major money centers have established foreign currency futures markets during the past decade, notably in New York (New York Futures Exchange, a subsidiary of the New York Stock Exchange), London (London International Financial Futures Exchange), Canada, Australia, and Singapore. So far, however, none of these rivals has come close to duplicating the trading volume of the IMM.

B. Contract Specifications

Contract specifications are defined by the exchange on which they are traded. The major features that must be standardized are the following:

• A specific sized contract. A German mark contract is for DM125,000. Consequently, trading can be done only in multiples of DM125,000.

• A standard method of stating exchange rates. American terms are used; that is, quotations are the dollar cost of foreign currency units.

• A standard maturity date. Contracts mature on the third Wednesday of January, March, April, June, July, September, October, or December. However, not all of these maturities are available for all currencies at any given time. “Spot month” contracts are also traded. These are not spot contracts as that term is used in the interbank foreign exchange market, but are rather short-term futures contracts that mature on the next following third Wednesday, that is, on the next following standard maturity date.

• A specified last trading day. Contracts may be traded through the second business day prior to the Wednesday on which they mature. Therefore, unless holidays interfere, the last trading day is the Monday preceding the maturity date.

• Collateral. The purchaser must deposit a sum as an initial margin or collateral. This is similar to requiring a performance bond and can be met by a letter of credit from a bank, Treasury bills, or cash. In addition, a maintenance margin is required. The value of the contract is marked-to-market daily, and all changes in value are paid in cash daily. The amount to be paid is called the variation margin.

EXAMPLE 49

The initial margin on a £62,500 contract may be US$ 3,000, and the maintenance margin US$ 2,400. The initial US$ 3,000 margin is the initial equity in your account. The buyer’s equity increases (decreases) when prices rise (fall). As long as the investor’s losses do not exceed US$ 600 (that is, as long as the investor’s equity does not fall below the maintenance margin, US$ 2,400), no margin call will be issued to him or her. If his or her equity, however, falls below US$ 2,400, he or she must add variation margin that restores his or her equity to US$ 3,000 by the next morning.

• Settlement. Only about 5% of all futures contracts are settled by the physical delivery of foreign exchange between the buyer and seller. Most often, buyers and sellers offset their original position prior to delivery date by taking an opposite position. That is, if one had bought a futures contract, that position would be closed out by selling a futures contract for the same delivery date. The complete buy/sell or sell/buy is called a round turn.

• Commissions. Customers pay a commission to their broker to execute a round turn and only a single price is quoted. This practice differs from that of the interbank market, where dealers quote a bid and an offer and do not charge a commission.

• Clearing house as counterparty. All contracts are agreements between the client and the exchange clearing house, rather than between the two clients. Consequently, clients need not worry that a specific counterparty in the market will fail to honor an agreement.

Currency futures contracts are currently available in over ten currencies including the British pound, Canadian dollar, Deutsche mark, Swiss franc, Japanese yen, and Australian dollar. The IMM is continually experimenting with new contracts. Those that meet the minimum volume requirements are added and those that do not are dropped. The number of contracts outstanding at any one time is called the open interest. Contract sizes are standardized according to amount of foreign currency—for example, £62,500, C$100,000, SFr 125,000. Exhibit 43 shows contract specifications. Leverage is high; margin requirements average less than 2% of the value of the futures contract. The leverage assures that investors’ fortunes will be decided by tiny swings in exchange rates. The contracts have minimum price moves, which generally translate into about S10 to S12 per contract. At the same time, most exchanges set daily price limits on their contracts that restrict the maximum price daily move. When these limits are reached, additional margin requirements are imposed and trading may be halted for a short time. Instead of using the bid-ask spreads found in the interbank market, traders charge commissions. Though commissions will vary, a round trip—that is, one buy and one sell—costs as little as $15. The low cost, coupled with the high degree of leverage, has provided a major incentive for speculators to participate in the market.

EXHIBIT 43

Chicago Mercantile Exchange Foreign Currency Futures Specifications*

| Austrian | British | Canadian | Deutsche | Japanese | ||

| Dollar | Pound | Dollar | Mark Swiss Franc | French Franc | Yen | |

| Symbol | AD | BP | CD | DM SF | FR | JY |

| Contract size | A$100,000 | £62,500 | C$100,000 | DM125,000 SFr125,000 | FFr500,000 | ¥12,500,000 |

| Margin | ||||||

| requirements | ||||||

| Initial | $1,148 | $1,485 | $608 | $1,755 $2,565 | $1,755 | $4,590 |

| Maintenance | $850 | $1,100 | $450 | $1,300 $1,900 | $1,300 | $3,400 |

| Minimum | 0.00001 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 0.0001 | 0.00002 | 0.000001 |

| Price Change | (1 pt.) | (2 pts.) | (1 pt.) | (1 pt.) (1 pt.) | (2 pts.) | (1 pt.) |

| Value of 1 point | $10.00 | $6.25 | $10.00 | $12.50 $12.50 | $12.50 | $10.00 |

| Months traded | January, March, April, June, July, September, October, December, and spot month | |||||

| Last day of | The second business day immediately preceding the third Wednesday of the delivery month | |||||

| trading | ||||||

| Trading Hours | 7:20 A.M.-2:00 P.M. (Central Time) | |||||

Note: Contract specifications are also available for currencies such as Brazilian real, Mexican peso, Russian ruble, and New Zealand dollar.

C. Futures Contracts on Euros

The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) has developed futures contracts on euros so that MNCs can easily hedge their positions in euros, as shown in Exhibit 44. U.S.-based MNCs commonly consider the use of the futures contract on the euro with respect to the dollar (column 2). However, there are also futures contracts available on cross-rates between the euro and the British pound (column 3), the euro and the Japanese yen (column 4), and the euro and the Swiss franc (column 5). Settlement dates on all of these contracts are available in March, June, September, and December. The futures contracts on cross-rates allow for easy hedging by foreign subsidiaries that wish to exchange euros for widely used currencies other than the dollar.

EXHIBIT 44

Futures Contracts on Euros

| Euro/U.S.$ | Euro/Pound | Euro/Yen | Euro/Swiss franc | |

| Ticker Symbol | EC | RP | RY | RF |

| Trading Unit | 125,000 euros | 125,000 euros | 125,000 euros | 125,000 euros |

| Quotation | $ per euro | Pounds per euro | Yen per euro | SF per euro |

| Last Day of Trading | Second business day before third Wednesday of the contract month | |||

D. Reading Newspaper Quotations

Futures trading on the IMM in Japanese yens for a Tuesday was reported as shown in Exhibit 45.

EXHIBIT 45

Foreign Currency Futures Quotations

| Lifetime | Open | ||||

| Open | High Low Settle Change | High | Low | Interest | |

| JAPAN YEN (CME)—12.5 million yen; $ per | yen (.00) | ||||

| Sept | .9458 | .9466 .9386 .9389 -.0046 | .9540 | .7945 | 73,221 |

| Dec | .9425 | .9470 .9393 .9396 -.0049 | .9529 | .7970 | 3,455 |

| Mar | . … … . .9417 -.0051 | .9490 | .8700 | 318 | |

| Est vol 28,844; vol Wed 36,595; open int 77,028 + 1.820 | |||||

The head, JAPAN YEN, shows the size of the contract (12.5M yen) and states that the prices are stated in US$ cents. The June 2000 contract had expired more than a month previously, so the three contracts being traded on July 29, 2000, are the September 2000, December 2000, and the March 2001 contracts. Detailed descriptions of the quotations follow:

1. In each row, the first four prices relate to trading on Thursday, July 29—the price at the start of trading (open), the highest and lowest transaction price during the day, and the settlement price (“Settle”), which is representative of the transaction prices around the close. The settlement (or closing) price is the basis of marking to market.

2. The column “Change” contains the change of today’s settlement price relative to yesterday’s. For instance, on Thursday, July 29, the settlement price of the September contract dropped by 0.0046 cents, implying that a holder of a purchase contracthas lost 12.5m x (0.0046/100) = US$ 575 per contract and that a seller has made US$ 575 per contract.

3. The next two columns show the extreme (highest and lowest) prices that have been observed over the contract’s trading life. For the March contract, the “High-Low” range is narrower than for the older contracts, because the March contract has been trading for only a little more than a month.

4. “Open Interest” refers to the number of contracts still in effect at the end of the previous day’s trading session. Each unit represents a buyer and a seller who still have a contract position. Notice how most of the trading is in the nearest-maturity contract. Open interest in the March’ 01 contract is minimal, and there has not even been any trading that day. (There are no open, high, and low data.) The settlement price for the March’01 contract has been set by the CME on the basis of bid-ask quotes.

5. The line below the price information gives an estimate of the volume traded that day and the previous day (Wednesday). Also shown are the total open interest (the total of the right column) across the three contracts, and the change in open interest from the prior trading day.

E. Currency Futures Quotations Reported Online

Exhibit 46 displays a currency quotation from Commodities, Charts & Quotes—Free (http://www.tfc-charts.w2d.com).

EXHIBIT 46

| (0\ Commodity Futures Price Quotes For \

{ CME Australian Dollar (Price quotes for this commodity delayed at least 10 minutes as per exchange requirements) |

|||||||||||||

| (3) | Click here to refresh data | ||||||||||||

| Month | (4) | SessionlO) | (6) (7) | Prior Day | Options | ||||||||

| Click for chart | Open | High | Low | Last | Time | Sett | Chg | Sett | Vol | O.Int | |||

| Dec 99 | 6362 | 6410 | 6350 | dn 6386 | 15:09 | 6388 | +8 | 6378 | 82 | 22197 | Call Put | ||

| Mar 00 | 6375 | 6412 | 6370 | up 6375 | 08:31 | 6398 | -13 | 6388 | 1 | 112 | Call Put | ||

| Jun 00 | - | - | - | uc 6398 | 12:43 | 6408 | - | 6398 | 2 | 11 | Call Put | ||

| Sep 00 | - | - | - | uc 6408 | 09:28 | 6418 | - | 6408 | - | 1 | Call Put | ||

Explanatory Notes:

(1) The name of the currency, Australian Dollar.

(2) The name of the exchange, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange.

(3) The delivery date (closing date for the contract).

(4) The opening, high, and low prices for the trading day. The trading unit is 100,000 Australian Dollars. The price is $10 per point. Therefore, the settlement price for the trading unit is $63,620, and each Australian Dollar being delivered in December is worth $.6362.

(5) The last price at which the contract traded.

(6) The “official” daily closing price of a futures contract, set by the exchange for the purpose of settling margin accounts.

(7) The change in the price from the prior settlement price to the last price quoted.

F. Foreign Currency Futures Versus Forward Contracts

Foreign currency futures contracts differ from forward contracts in a number of important ways. Nevertheless, both futures and forward contracts are used for the same commercial and speculative purposes. Exhibit 47 provides a comparison of the major features and characteristics of the two instruments.

EXHIBIT 47

Basic Differences of Foreign Currency Futures and Forward Contracts

| Characteristics | Foreign Currency Futures | Forward Contracts |

| Trading and location | In an organized exchange | By telecommunications |

| networks | ||

| Parties involved | Unknown to each other | In direct contact with each |

| other in setting contract | ||

| specifications. | ||

| Size of contract | Standardized | Any size individually tailored |

| Maturity | Fixed | Delivery on any date |

| Quotes | In American terms | In European terms |

| Pricing | Open outcry process | By bid and offer quotes |

| Settlement | Made daily via exchange clearing | Normally delivered on the |

| house; rarely delivered | date agreed | |

| Commissions | Brokerage fees for buy and sell | Based on bid-ask spread |

| (roundtrip) | ||

| Collateral and margin | Initial margin required | No explicit margin specified |

| Regulation | Highly regulated | Self-regulating |

| Liquidity and volume | Liquid but low volume | Liquid but large volume |

| Credit risk | Low risk due to the exchange | Borne by each party |

| clearing house involved |

The following example illustrates how currency futures contracts are used for hedging purposes and gains and losses calculations, and how they compare with currency options.

EXAMPLE 50

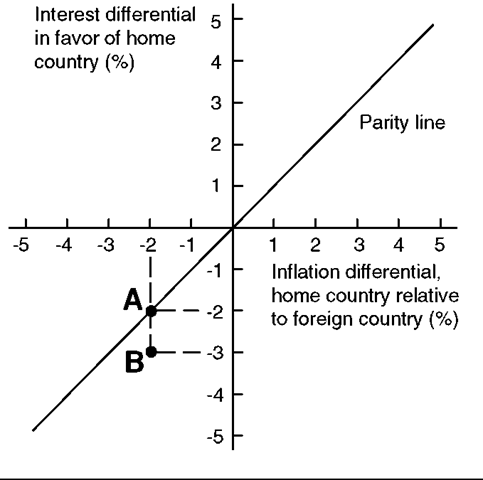

TDQ Corporation must pay its Japanese supplier ¥125 million in three months. The firm iscontemplating two alternatives:

1. Buying 20 yen call options (contract size is ¥6.25 millions) at a strike price of $0.00900 in order to protect against the risk of rising yen. The premium is $0.00015 per yen.

2. Buying 10 3-month yen futures contracts (contract size is ¥12.5 million) at a price of $0.00840 per yen. The current spot rate is $0.008823/¥. The firm’s CFO believes that the most likely rate for the yen is $0.008900, but the yen could go as high as $0.009400 or as low as $0.008500.

Note: In all calculations, the current spot rate $0.008823/¥ is irrelevant.

1. For the call options, TDQ must pay a call premium of $0.00015 x 125,000,000 = $18,750. If the yen settles at its minimum value, the firm will not exercise the option and it loses the entire call premium. But if the yen settles at its maximum value of $0.009400, the firm willexercise at $0.009000 and earn $0.0004/¥ for a total gain of $0.0004 x 125,000,000 = $50,000. TDQ’s net gain will be $50,000 – $18,750 = $31,250. 2. By using a futures contract, TDQ will lock in a price of $0.008940/¥ for a total cost of $0.008940 x 125,000,000 = $992,500. If the yen settles at its minimum value, the firm will lose $0.008940 – $0.008500 = $0.000440/¥ (remember the firm is buying yen at $0.008940, when the spot price is only $0.008500), for a total loss on the futures contract of $0.00044 x 125,000,000 = $55,000. But if the yen settles at its maximum value of $0.009400, the firm will earn $0.009400 – $0.008940 = $0.000460/¥, for a total gain of $0.000460 x 125,000,000 = $57,500.

Exhibits 48 and 49 present profit and loss calculations on both alternatives and their corresponding graphs.

EXHIBIT 48

Profit or Loss on TDQ’s Options and Futures Positions

| Contract size: | 125,000,000 | Yens | |||

| Expiration date: | 3.0 | months | |||

| Exercise or strike price: | 0.00900 | $/Yen | |||

| Premium or option price: | 0.00015 | $/Yen | |||

| (1) CALL OPTION | |||||

| Ending spot | |||||

| rate ($/Yen) | 0.00850 | 0.00894 | 0.00915 | 0.00940 | 0.00960 |

| Payments | |||||

| Premium | (18,750) | (18,750) | (18,750) | (18,750) | (18,750) |

| Exercise | |||||

| cost | 0 | 0 | (1,125,000) | (1,125,000) | (1,125,000) |

| Receipts | |||||

| Spot sale | 0 | 0 | 1,143,750 | 1,175,000 | 1,200,000 |

| of Yen | |||||

| Net ($) | (18,750) | (18,750) | 0 | 31,250 | 56,250 |

| (2) FUTURES | Lock-in price = | 0.008940$/Yen | |||

| Receipts | 1,062,500 | 1,117,500 | 1,143,750 | 1,175,000 | 1,200,000 |

| Payments | (1,117,500) | (1,117,500) | (1,117,500) | (1,117,500) | (1,117,500) |

| Net ($) | (55,000) | 0 | 26,250 | 57,500 | 82,500 |

Exhibit 50 provides a comparison between a futures contract and an option contract.

FOREIGN CURRENCY OPERATIONS

Also called foreign-exchange market intervention, foreign currency operations involve purchase or sale of the currencies of other countries by a central bank in order to influence foreign exchange rates or maintaining orderly foreign exchange markets.

EXHIBIT 49

TDQ’s Profit (Loss) on Options and Futures Positions

EXHIBIT 50

Currency Futures Versus Currrency Options

| Futures | Options |

| A futures contract is most valuable when the | An options contract is most valuable when the |

| quantity of foreign currency being hedged is | quantity of foreign currency is unknown. |

| known. | |

| A futures contract provides a “two-sided” | An options contract enables the hedging of a |

| hedge against currency movements. | “one-sided” risk either with a call or with a |

| put. | |

| A buyer of a currency futures contract must | A buyer of a currency options contract has the |

| take delivery. | right (not the obligation) to complete the |

| contract. |

FOREIGN CURRENCY OPTION

A financial contract that gives the holder the right (but not the obligation) to exercise it to purchase/sell a given amount of foreign currency at a specified price during a fixed time period. Contract specifications are similar to those of futures contracts except that the option requires a premium payment to purchase (and it does not have to be exercised). See also CURRENCY OPTION.

FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

Foreign direct investment (FDI) involves ownership of a company in a foreign country. In exchange for the ownership, the investing company usually transfers some of its financial, managerial, technical, trademark, and other resources to the foreign country. In the process, productive activities in different countries come under the ownership control of a single firm (MNC). It is the control aspect which distinguishes FDI from its near relations such as exporting, portfolio investments, and licensing. Such investment may be financed in many ways: the parent firm can transfer funds to the new affiliate and issue ownership shares to itself; the parent firm can borrow all of the required funds locally in the new country to pay for ownership; and many combinations of these and other alternatives can be adopted. The key point is that no international transfer of funds is necessary; it requires only transfer of ownership to the investing MNC. Types of foreign direct investments include extractive, market-serving, horizontal, vertical, agricultural, industrial, and service industries. Horizontal FDI is FDI in the same industry in which a firm operates at home, while vertical FDI is FDI in an industry that provides inputs for a firm’s domestic operations. FDI is distinguished from portfolio investments that are made to earn investment income or capital gains. Exhibit 51 presents some basic reasons for FDI.

EXHIBIT 51

Strategic Reasons for Foreign Direct Investment

| Demand Side | Supply Side |

| To serve a portfolio of markets and to explore new markets | To lower production and delivery costs |

| To enter an export market closed by restrictions such as a quota or tariff | To acquire a needed raw material |

| To establish a local presence | To do offshore assembly |

| To accommodate “buy national” regulations | To respond to rivals’ threats |

| To gain visibility as a local firm, employing | To build a “portfolio” of manufacturing |

| local workforce, paying local taxes, etc. | resources |

FOREIGN EXCHANGE

Foreign exchange (FOREX) is not simply currency printed by a foreign country’s central bank. Rather, it includes such items as cash, checks (or drafts), wire transfers, telephone transfers, and even contracts to sell or buy currency in the future. Foreign exchange is really any financial transaction that fulfills payment from one currency to another. The most common form of foreign exchange in transactions between companies is the draft (denominated in a foreign currency). The most common form of foreign exchange in transactions between banks is the telephone transfer. A foreign exchange market is available for trading foreign exchanges.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE ARBITRAGE

Foreign exchange arbitrage involves simultaneous contracting in two or more foreign exchange markets to buy and sell foreign currency, profiting from exchange rate differences without suffering currency risk. Foreign exchange arbitrage may be two-way (simple), three-way (triangular), or intertemporal; and it is generally undertaken by large commercial banks that can exchange large quantities of money to exploit small rate differentials. See also INTERTEMPORAL ARBITRAGE; SIMPLE ARBITRAGE; TRIANGULAR ARBITRAGE.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE HEDGING

Foreign exchange hedging involves protecting against the possible impact of exchange rate changes on the firm’s business by balancing foreign currency assets with foreign currency liabilities. Elimination of all foreign exchange risk is not necessarily the objective of a financial manager. Risk is a two-way street; gains are possible as well as losses. If gains from exchange-rate fluctuations appear more likely than losses, then it may make sense to bear the currency risk (that is, retain the exchange-rate exposure) so that gains may be realized. Another important consideration is that elimination of exchange risk entails a cost. In a cost-benefit analysis, elimination of all exchange risk may not be beneficial, while elimination of part of the risk may be. Exchange risk may be neutralized or hedged by a change in the asset and liability position in the foreign currency. An exposed asset position can be hedged or covered by creating a liability of the same amount and maturity denominated in the foreign currency. An exposed liability position can be covered by acquiring assets of the same amount and maturity in the foreign currency.

The objective, in the hedging strategy, is to have zero net asset position in the foreign currency. This eliminates exchange risk, because the loss (gain) in the liability (asset) is exactly offset by the gain (loss) in the value of the asset (liability) when the foreign currency appreciates (depreciates). Two popular forms of hedge are the money-market hedge and the forward market hedge. In both types of hedge the amount and the duration of the asset (liability) positions are matched. Many MNCs take long or short positions in the foreign exchange market, not to speculate, but to offset an existing foreign currency position in another market. Note: The forward market hedge is not adequate for some types of exposure. If the foreign currency asset or liability position occurs on a date for which forward quotes are not available, then the forward hedge cannot be accomplished. In these situations, MNCs may have to rely on other techniques such as leading and lagging.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET

A foreign exchange (FOREX) market is a market where foreign exchange transactions take place, that is, where different currencies are bought and sold. Or, more broadly, a foreign exchange market is a market for the exchange of financial instruments denominated in different currencies. The most common location for foreign exchange transactions is a commercial bank, which agrees to “make a market” for the purchase and sale of currencies other than the local one. This market is not located in any one place, most transactions being conducted by telephone, wire service, or cable. It is a global network of banks, investment banks, and brokerage houses that makeup an electronically linked infrastructure servicing international corporations, banks, and investment funds. FOREX trading follows the sun around the world—starting in Tokyo, the market activity moves through to London, the last banking center in Europe, before traveling on to New York and finally returning to Japan via Sydney. The interbank market has three sessions of trading. The first begins on Sunday at 7:00 p.m., NYT, which is the Asia session. The second is the European (London) session, which begins at approximately 3:00 a.m.; and the third and final session is the New York, which begins at approximately 8:00 a.m. and ends at 5:00 p.m. The majority of all trading occurs during the London session and the first half of the New York session. As a result, buyers and sellers are available 24 hours a day. Investors can respond to currency fluctuations caused by economic, social, and political events at the time they occur—day or night.

The functions of the foreign exchange market are basically threefold: (1) to transfer purchasing power, (2) to provide credit, and (3) to minimize exchange risk. The foreign exchange market is dominated by:

1. Large commercial banks (thus often called bank market);

2. Nonbank foreign exchange dealers, commercial customers (primarily MNCs) conducting commercial and investment transactions;

3. Foreign exchange brokers who buy and sell foreign currencies and make a profit on the difference between the exchange rates and interest rates among the various world financial centers; and

4. Central banks, which intervene in the market from time to time to smooth exchange rate fluctuations or to maintain target exchange rates (for example, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in the U.S.).

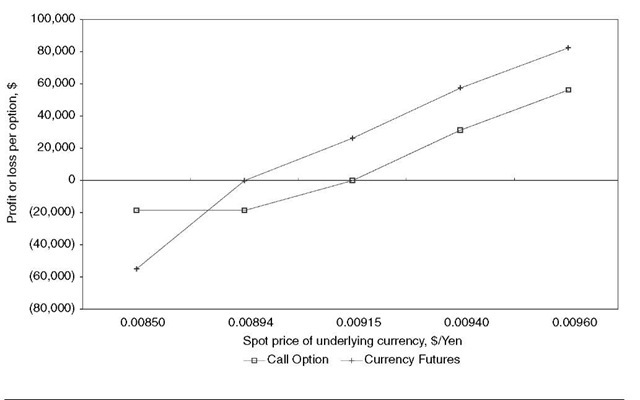

In addition to the settlement of obligations incurred through investment, purchases, and other trading, the foreign exchange market involves speculation in exchange futures. New York, Tokyo, and London are the major centers for these transactions. The various linkages between banks and their customers in the foreign exchange market are displayed in Exhibit 52. Exhibit 53 is a list of a variety of participants in the foreign exchange market.

EXHIBIT 52

Structure of Foreign Exchange Markets

EXHIBIT 53

Participants in the Foreign Exchange Market

| Suppliers of Foreign Currency (e.g., ¥) | Demanders for Foreign Currency (e.g., ¥) |

| U.S. exporters | U.S. direct investors in Japan |

| Japanese direct investors remitting profits | Japanese foreign investors in the U.S. remitting their |

| profits | |

| Japanese portfolio investors | U.S. portfolio investors |

| Bear speculators | Bull speculators |

| Arbitrageurs | |

| Government interveners |

Exhibit 54 shows the major economics forces moving today’s FOREX markets, while Exhibit 55 chronicles the history of the FOREX market.

EXHIBIT 54

Economics Forces Moving Today’s FOREX Markets

| Economic Indicators | Leading Indicators |

| Balance of Payments | Employment Cost Index |

| Trade Deficits | Consumer Price Index (CP |

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | Produce Price Index (PPI) |

| Industrial Production | Retail Sales |

| Unemployment Rate | Prime Rate |

| Business Inventories | Discount Rate |

| Federal Funds Rate | |

| Personal Income |

EXHIBIT 55

History of the FOREX Market

1944—The major Western Industrialized nations agree to attempt to “stabilize” their currencies. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is created and the U.S. dollar is “pegged” at $35.00 to the Troy ounce of gold. This was known as the Gold Standard.

1971—President Nixon abandons the Gold Standard, directly pegging major currencies to the U.S. dollar. 1973—Following the second major devaluation in the U.S. dollar, the fixed-rate mechanism is totally discarded by the U.S. Government and replaced by the Floating Rate. All major currencies seek to move independently of each other.

1999—Eleven European nations unite under one currency, the euro, and resolve to have a single monetary policy set by the European Central Bank (ECB).

Today—Leading global investment firms have made programs available for individual investors to capitalize on the opportunities offered. The FOREX interbank market was developed as a means of handling the huge transaction business in trading, lending, and consolidating deposits of foreign currencies. The vast size and volume of the FOREX market makes it impossible to manipulate the market for any length of time. As a result, FOREX is an action-based, decentralized international forum that allows various major currencies of the world to seek their true value.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE RATE

A foreign exchange rate, or exchange rate for short, specifies the number of units of a given currency that can be purchased with one unit of another currency. Exchange rates appear in the business sections of newspapers each day and financial dailies such as Investor’s Business Daily and The Wall Street Journal. Exchange rates are also available at many finance Web sites such as the Bloomberg World Currency Values Web site (http://www.bloomberg.com/mar-kets/wcv.html). The actual exchange rate is determined by the interaction of supply and demand in the foreign exchange market. Such supply and demand conditions are determined by various economic factors (e.g., whether the country’s basic balance of payments position is in surplus or deficit). Exchange rates can be quoted in direct or indirect terms and in American terms or European terms. Exchange rates can be fixed at a predetermined level (fixed exchange rate), or they can be flexible to reflect changes in demand (floating exchange rate). Foreign exchange is the instruments used for international payments. Exchange rates can be spot (cash) or forward. Foreign exchange rates are determined in various ways:

1. Fixed exchange rates are an international financial arrangement in which governments directly intervene in the foreign exchange market to prevent exchange rates from deviating more than a very small margin from some central or parity value. From the end of World War II until August 1971, the world was on this system.

2. Flexible (floating exchange) rates are an arrangement by which currency prices are allowed to seek their own levels without much government intervention (i.e., in respond to market demand and supply). Arrangements may vary from free float (i.e., absolutely no government intervention) to managed float (i.e., limited but sometimes aggressive government intervention in the foreign exchange market).

3. Forward exchange rate is the exchange rate in contract for receipt of and payment for foreign currency at a specified date, usually 30, 90, or 180 days in the future, at a specified current or “spot” (or cash) price. By buying and selling forward exchange, importers and exporters can protect themselves against the risks of fluctuations in the current exchange market.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE RATE FORECASTING

The forecasting of exchange rates is different under the freely floating and fixed exchange rate systems. Nevertheless, exchange rate forecasting in general is a very difficult and time-consuming task, because so many possible factors are involved. Therefore it might be worthwhile for firms to always hedge their future cash flows in order to eliminate the exchange rate risk and to have predictable cash flows and earnings. With the world becoming smaller and the businesses getting more and more multinational, companies are increasingly exposed to transaction risk, the risk that comes from a fluctuation in the exchange rate between the time a contract is signed and when the payment is received. With most of the exchange rates floating nowadays, they can vary easily as much as 5% within a week, and the exchange rate risk is therefore very considerable. There are four primary reasons why it is imperative to forecast the foreign exchange rates.

1. Hedging Decision: Multinational companies (MNCs) are constantly faced with the decision of whether to hedge payables and receivables in foreign currency. An exchange rate forecast can help MNCs determine if they should hedge their transactions. As an example, if forecasts determine that the Swiss franc is going to appreciate in value relative to the dollar, a company expecting payment from a Swiss partner in the future may decide not to hedge the transaction. However, if the forecasts showed that the Swiss franc is going to depreciate relative to the dollar, the U.S. partner should hedge the transaction.

2. Short-Term Financing Decision for MNC: A large corporation has several sources of capital market and several currencies in which it can borrow. Ideally, the currency it would borrow would exhibit low interest rate and depreciate in value over the financial period. For example, a U.S. firm could borrow in Japanese yens; during the loan period, the yens would depreciate in value. At the end of the period, the company would have to use fewer dollars to buy the same amount of yens and would benefit from the deal.

3. International Capital Budgeting Decision: Accurate cash flows are imperative in order to make a good capital budgeting decision. In case of international projects, it is not only necessary to establish accurate cash flows but it is also necessary to convert them into an MNC’s home country currency. This necessitates the use of foreign exchange forecast to convert the cash flows and there after, evaluate the decision.

4. Subsidiary Earning Assessment for MNC: When an MNC reports its earning, international subsidiary earnings are often translated and consolidated in the MNC’s home country currency. For example, when Nokia makes a projection for its earnings, it needs to project its earnings in Japan, then it needs to translate these earnings from Japanese yens into U.S. dollars. A depreciation in yens would decrease a subsidiary’s earnings and vice versa. Thus, it is necessary to generate an accurate forecast of yens to create a legitimate earnings assessment.

A. Forecasting Under a Freely Floating Exchange Rate System

Future spot rates are theoretically determined by the interplay of various economic factors:

• The expected inflation differential between countries (purchasing power parity)

• The difference between national interest rates (Fisher and International Fisher Effects)

• The forward premium or discount compared with the differences in short-term interest rates (interest rate parity)

Under the assumption that the foreign exchange market is reasonably efficient, the forward rate can be used as an unbiased predictor of the spot rate, which is called market-based forecasting. Under floating exchange rates the expected rates of change in the spot rate, differential rates of national inflation and interest, and the forward discount or premium are directly proportional to each other and mutually determined. With an efficient market all the variables adjust very quickly to changes in any one of them. Market efficiency assumes that (a) all relevant formation is quickly reflected in both the spot and forward markets, (b) transaction costs are low, and (c) instruments denominated in different currencies are perfect substitutes for one another.

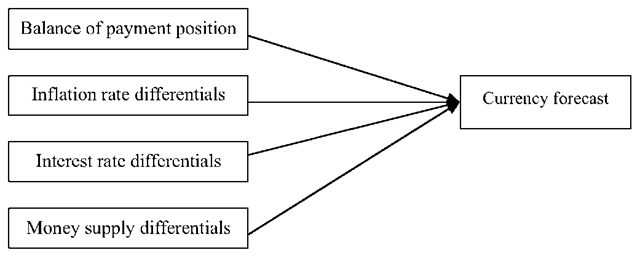

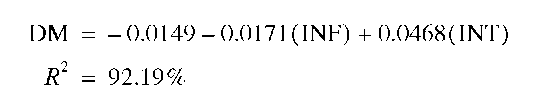

As a result, forecasting success depends heavily on having prior information that one of the variables is going to change. In an efficient market the possession of such information doesn’t bring a competitive edge, because all information is quickly reflected in both the spot and forward markets. Recent tests however are contradicting the efficient market theory, and, therefore, it might well be that the market is inefficient. In that case it pays for a firm to spend resources on forecasting exchange rates. Therefore, forecasters spend a lot of time with fundamental analysis. This approach involves examining the macroeconomic variables and policies that are likely to influence a currency’s performance, basically spot and forward exchange rates, interest rates, and rates of inflation. Another forecasting approach is technical analysis, which focuses exclusively on past price and volume movements, while completely ignoring economic and political factors. The two primary methods of technical analysis are charting and trend analysis. The objective is to find particular trends from where you can make predictions for the future. Probably the best forecasting method is a mixture of the three methods, because there are more variables involved and this might produce a better result than relying on only a single forecast. Exhibit 56 lists variables used to forecast future exchange rate movements.

EXHIBIT 56

Variables Used to Forecast Future Exchange Rate Movements

B. Forecasting under a Managed or Fixed Exchange Rate System

Under fixed exchange rates the movement toward equilibrium in spot and forward exchange rates, interest rates, and inflation rates, which occurs under freely floating rates, is artificially prevented from happening. The government is responsible for keeping the exchange rate at a certain level with all means, even if it means accepting huge losses. However, even the government must resign to the market pressure and allow the exchange rate to change. The objective of exchange rate forecasting is how to predict when this change will occur. The timing and amount of fixed exchange rates are primarily a political decision and, therefore, forecasters have to consider various economic factors:

• Balance of payments deficit: If more imports than exports and hence more monetary claims against the country exist, a devaluation becomes more likely.

• Differential rates of inflation: Goods in the country with lesser inflation become cheaper, which leads to a balance of payment surplus in this country, because there is more demand for the goods. Hence this currency would appreciate.

• Growth in money supply: If money supply grows faster than is warranted by real economic growth, inflation will incur and there will be pressure on the exchange rate as explained above.

• Decline in international monetary reserves: Balance of payments deficits will lead to a decline in international monetary reserves, which might lead to a run on the currency.

• Excessive government spending: If resources of a nation are overextended, it might lead to currency devaluation.

Exchange rate forecasting is, in reality, neglected in many firms. It is often argued that forecasting is useless because it does not provide an accurate estimate. It is certainly true that forecasting will not provide an accurate estimate, because the future is uncertain and every forecast can be only an approximation, which is based on uncertain variables. Despite the fact that forecasting will not provide an exact result, it is nevertheless not useless because it gives the company a general idea about the overall trend of the future, which ensures that they won’t be caught sleeping when new trends happen. Besides, exchange rate forecasting gives companies an idea about when and how to hedge. Moreover, it is important to forecast exchange rates for the predictability of future cash flows. All in all, exchange rate forecasting is a very difficult and time-consuming task, because so many possible factors are involved. Therefore, it might be worthwhile for firms to always hedge their future cash flows in order to eliminate the exchange rate risk and to have predictable cash flows and earnings.

Exhibit 57 compares forecasts of Malaysia’s ringgit drawn from each forecasting technique.

EXHIBIT 57

Forecasts of Malaysia’s Ringgit Drawn from Each Forecasting Method

| Method | Factors Considered | Situation | Possible Forecast |

| Fundamental | Inflation, interest rates, | Malaysia’s interest rates are | The ringitt’s value will go |

| economic growth | high while inflation rate is | up as U.S. investors take | |

| stable | advantage of the high | ||

| interest rates by investing | |||

| in Malaysian securities | |||

| Technical | Recent movements—chart | The ringgit’s value fell in | The ringitt’s value will |

| and trend | the past few weeks below | continue to decline now | |

| a specific threshold level | that it is beyond the | ||

| threshold level | |||

| Market-based | Spot rate, forward rate | The ringitt’s forward rate | Based on the predicted |

| shows a significant | forward rate discount, the | ||

| discount, which is due to | ringitt’s value will fall | ||

| Malaysia’s relatively high | |||

| interest rates | |||

| Mixed | Weighted average | Interest rates are high; | There is better than 50% |

| forward rate discount | chance that the ringitt’s | ||

| displayed; the ringitt’s | value will decline | ||

| value of recent weeks has | |||

| headed lower |

C. Currency Forecasting Service

The corporate need to forecast currency values has prompted the emergence of several consulting firms, including Business International, Conti Currency, Predex, and Wharton Econometric Forecasting Associates (WEFA). In addition, some large investment banks, such as Goldman Sachs, and commercial banks, such as Citibank, Chemical Bank, and Chase Manhattan Bank, offer forecasting services. Many consulting services use at least two different types of analysis to generate separate forecasts, and then determine the weighted average of the forecasts.

Some forecasting services, such as Capital Techniques, FX Concepts, and Preview Economics, focus on technical forecasting, while other services, such as Corporate Treasury Consultants Ltd. and WEFA, focus on fundamental forecasting. Many services, such as Chemical Bank and Forexia Ltd., use both technical and fundamental forecasting. In some cases, the technical forecasting techniques are emphasized by the forecasting firms for short-term forecasts, while fundamental techniques are emphasized for long-term forecasts.

Recently, most forecasting services have been inaccurate regarding future currency values. Given the recent volatility in foreign exchange markets, it is quite difficult to forecast currency values. One way for a corporation to determine whether a forecasting service is valuable is to compare the accuracy of its forecasts to those of alternative publicly available and free forecasts. The forward rate serves as a benchmark for comparison here, because it is quoted in many newspapers and magazines. A recent study compared the forecasts of several currency forecasting services regarding nine different currencies to the forward rate. Only 5% of the forecasts (when considering all forecasting firms and all currencies forecasted) for one month ahead were more accurate than the forward rate, while only 14% of forecasts for three months ahead were more accurate. These results are frustrating to the MNCs that have paid $25,000 or more per year for expert opinions. Perhaps some corporate clients of these consulting firms believe the fee is worth it even when the forecasting performance is poor, if other services (such as cash management) are included in the package. It is also possible that a corporate treasurer, in recognition of the potential for error in forecasting exchange rates, may prefer to pay a consulting firm for its forecasts. Then the treasurer is not (in a sense) directly responsible for corporate problems that result from inaccurate currency forecasts. Not all MNCs hire consulting firms to do their forecasting. For example, Kodak, Inc. once used a service, but became dissatisfied with it and has now developed its own forecasting system.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE RISK PREMIUM

The foreign exchange risk premium is the difference between the forward rate and the expected future spot rate.

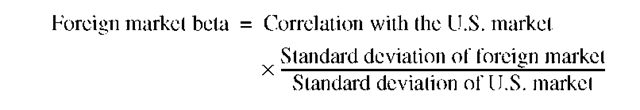

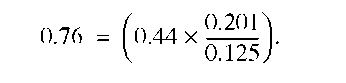

FOREIGN MARKET BETA

A foreign market beta is a measure of foreign market risk which is derived from the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). The formula for the computation is:

EXAMPLE 51

If the correlation between the German and U.S. markets is 0.44, and the standard deviations of German and U.S. returns are 20.1% and 12.5%, respectively, then the German market beta is

In other words, despite the greater riskiness of the German market relative to the U.S. market, the low correlation between the two markets leads to a German market beta (.76) which is lower that the U.S. market beta (1.00).

FOREIGN SUBSIDIARIES AND AFFILIATES

A foreign subsidiary bank is a separately incorporated bank owned entirely or in part by a U.S. bank, a U.S. bank holding company, or an Edge Act Corporation. A foreign subsidiary provides local identity and the appearance of a local bank in the eyes of potential customers in the host country, which often enhances its ability to attract additional local deposits. Furthermore, management is typically composed of local nationals, giving the subsidiary bank better access to the local business community. Thus, foreign-owned subsidiaries are generally in a stronger position to provide domestic and international banking services to residents of the host country.

Closely related to foreign subsidiaries are foreign affiliate banks, which are locally incorporated banks owned in part, but not controlled, by an outside parent. The majority of the ownership and control may be local, or it may be other foreign banks.

FORFAITING

Forfaiting is the simplest, most flexible and convenient form of medium-term fixed rate finance for export transactions. It is a form of export financing similar to factoring, which is the sale of export receivables by an exporter for cash. The word comes from the French a forfait, a term meaning “to forfeit or surrender a right.” It is the name given to the purchase of trade receivables maturing at various future dates without recourse to the exporter. The basic idea is to get the exporter’s goods shipped and received and for the exporter to receive payment for the goods. The exporter accepts one or a series of bills of exchange payable over a specified period of years. The exporter immediately turns around and sells these notes or bills of exchange to a forfait house. This sale is made without recourse to the exporter, who now has his goods delivered and the cash in hand. He is out of the picture. The only obligation that he still has is that the goods shipped were of the quality stated. The exporter is now free to go on to the next deal without the worry of extending credit and collecting. This keeps his cash flow moving in a positive direction. A specialized finance firm called a forfaiter buys trade receivables, notes, or bills of exchange and then repackages them for sale to investors. Forfaiting may also carry the guarantee of the foreign government. Under a typical arrangement, the exporter receives cash up front and does not have to worry about the financial ramifications of nonpayment, this risk being transferred to the forfaiter. The forfaiter carries all political, country, and commercial risk.

Forfaiting is the discounting—at a fixed rate without recourse—of medium-term export receivables denominated in fully convertible currencies (U.S. dollar, Swiss franc, Deutsche mark). This technique is typically used in the case of capital-goods exports with a five-year maturity and repayments in semiannual installments. The discount is set at a fixed rate—about 1.25% above the local cost of funds or above the London interbank offer rate (LIBOR). In a typical forfaiting transaction, an exporter approaches a forfaiter before completing a transaction’s structure. Once the forfaiter commits to the deal and sets the discount rate, the exporter can incorporate the discount into the selling price. Forfaiters usually work with bills of exchange or promissory notes, which are unconditional and easily transferable debt instruments that can be sold on the secondary market. Forfaiting differs from factoring in four ways: (1) forfaiting is relatively quick to arrange, often taking no more than two weeks; (2) forfaiting may be for years, while factoring may not exceed 180 days; (3) forfaiting typically involves political and transfer uncertainties but factoring does not; and (4) factors usually want access to a large percentage of an exporter’s business, while most forfaiters will work on a one-shot basis. A third party, usually a specialized financial institution, guarantees the financing. Many forfaiting houses are subsidiaries of major international banks, such as Credit Suisse. These houses also provide help with administrative and collection problems.

FORWARD CONTRACT

A forward contract is a written agreement between two parties for the purchase or sale of a stipulated amount of a commodity, currency, financial instrument, or other item at a price determined at the present time with delivery and settlement to be made at a future date, usually in 30, 90, or 180 days.

FORWARD EXCHANGE RATE

The forward exchange rate is the contracted exchange rate for receipt of and payment for foreign currency at a specified date in the future, at a stipulated current or spot price. In the forward market, you buy and sell currency for a future delivery date, usually 1, 3, or 6 months in advance. If you know you need to buy or sell currency in the future, you can hedge against a loss by selling in the forward market. By buying and selling forward exchange contracts, importers and exporters can protect themselves against the risks of fluctuations in the current exchange market. Suppose that the spot and the 90-day forward rates for the British pound are quoted as $1.5685 and $1.5551, respectively. You are required to pay £10,000 in 3 months to your English supplier. You can purchase £10,000 today by paying $15,551 (10,000 x $1.5551). These pounds will be delivered in 90 days. In the meantime you have protected yourself. No matter what the exchange rate of the pound or U.S. dollar is in 90 days, you are assured delivery at the quoted price. As can be seen in the example, the cost of purchasing pounds in the forward market ($15,551) is less than the price in the spot market ($15,685). This implies that the pound is selling at a forward discount relative to the dollar, so you can buy more pounds in the forward market. It could also mean that the U.S. dollar is selling at a forward premium. Note: It is extremely unlikely that the forward rate quoted today will be exactly the same as the future spot rate.

FORWARD FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET

Simply called forward market, the forward foreign exchange market is the market where foreign exchange dealers can enter into a forward contract to buy or sell any amount of a currency at any date in the future. Forward contracts are negotiated between the offering bank and the client as to size, maturity, and price. The rationale for forward contracts in currencies is analogous to that for futures contracts in commodities; the firm can lock in a price today to eliminate uncertainty about the value of a future receipt or payment of foreign currency. Such a transaction may be undertaken because the firm has made a previous contract, for example, to pay a certain sum in foreign currency to a supplier in three months for some needed inputs to its operations. This concept is called hedging. The principal users of the forward market are currency arbitrageurs, hedgers, importers and exporters, and speculators.

Arbitrageurs wish to earn risk-free profits; hedgers, importers, and exporters want to protect the home currency values of various foreign currency-denominated assets and liabilities; and speculators actively expose themselves to exchange risk to benefit from expected movements in exchange rates. It differs from the futures market in many significant ways.

FORWARD MARKET HEDGE

A forward market hedge is a hedge in which a net asset (liability) position is covered by a liability (asset) in the forward market.

EXAMPLE 52

XYZ, an American importer, enters into a contract with a British supplier to buy merchandise for £4,000. The amount is payable on delivery of the goods, 30 days from today. The company knows the exact amount of its pound liability in 30 days. However, it does not know the payable in dollars. Assume further that today’s foreign exchange rate is $1.50/£ and the 30-day forward exchange rate is $1.49. In a forward market hedge, XYZ may take the following steps to cover its payable.

Step 1. Buy a forward contract today to purchase (buy the pounds forward) £4,000 in 30 days. Step 2. On the 30th day pay the foreign exchange dealer $5,960.00 (4,000 pounds x $1.49/£) and collect £4,000. Pay this amount to the British supplier.

By using the forward contract, XYZ knows the exact worth of the future payment in dollars ($5,960.00). The currency risk in pounds is totally eliminated by the net asset position in the forward pounds.

Note: (1) In the case of the net asset exposure, the steps open to XYZ are the exact opposite: Sell the pounds forward (buy a forward contract to sell the pounds), and on the future day receive and deliver the pounds to collect the agreed-upon dollar amount. (2) The use of the forward market as a hedge against currency risk is simple and direct. That is, it matches the liability or asset position against an offsetting position in the forward market.

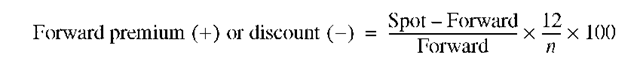

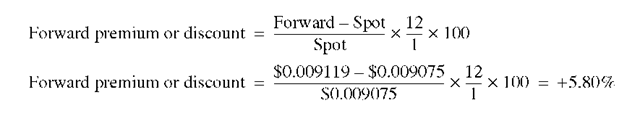

FORWARD PREMIUM OR DISCOUNT

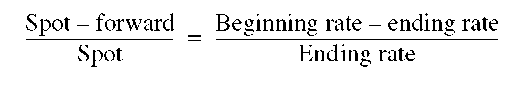

The forward rate is often quoted at a premium to or discount from the existing spot rate. The forward premium or discount is the difference between spot and forward rates, expressed as an annual percentage, also called forward-spot differential, forward differential, or exchange agio. When quotations are on an indirect basis, a formula for the percent-per-annum forward premium or discount is as follows:

where n = the number of months in the contract.

EXAMPLE 53

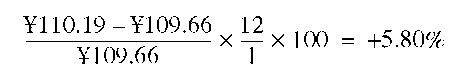

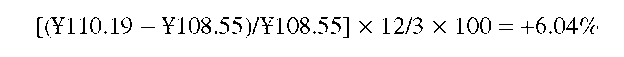

Assume that the spot exchange rate = ¥110/$ and the one-month forward rate = ¥109.66/$. Since the spot rate is greater than the one-month forward rate (in indirect quotes), the yen is selling forward at a premium.

The 1-month (30-day) forward premium (discount) is:

The 3-month (90-day) forward premium (discount) is:

The 6-month (180-day) forward premium (discount) is:

Note: A currency is said to be selling at a premium (discount) if the forward rate expressed in indirect quotes is less (greater) than the spot rate.

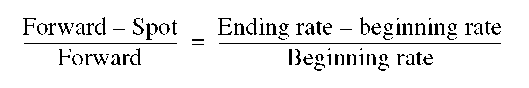

With direct quotes:

Note: A currency is said to be selling at a premium (discount) if the forward rate expressed in direct quotes is greater (less) than the spot rate.

Exhibit 58 shows forward rate quotations and annualized forward premiums (discounts). Note: In Exhibit 58, since a dollar would buy fewer yen in the forward than in the spot market, the forward yen is selling at a premium.

EXHIBIT 58

Forward Rate Quotations and Annualized Forward Premiums (Discounts)

| Quotation | ¥/$ (Indirect Quote) | $/¥ (Direct Quote) | % per Annum | |

| Spot Rate | ¥110.19 | $0.009075 | ||

| Forward | ||||

| 1-month | 109.66 | 0.009119 | +5.80% | |

| 3-month | 108.55 | 0.009212 | +6.04% | |

| 6-month | 106.83 | 0.009361 | +6.29% |

FORWARD RATE QUOTATIONS

The quotations for forward rates can be made in two ways. They can be made in terms of the amount of local currency at which the quoter will buy and sell a unit of foreign currency. This is called the outright rate and it is used by traders in quoting to customers. The forward rates can also be quoted in terms of points of discount and premium from spot, called the swap rate, which is used in interbank quotations. The outright rate is the spot rate adjusted by the swap rate. To find the outright forward rates when the premiums or discounts on quotes of forward rates are given in terms of points (swap rate), the points are added to the spot price if the foreign currency is trading at a forward premium; the points are subtracted from the spot price if the foreign currency is trading at a forward discount. The resulting number is the outright forward rate. It is usually well known to traders whether the quotes in points represent a premium or a discount from the spot rate, and it is not customary to refer specifically to the quote as a premium or a discount. However, this can be readily determined in a mechanical fashion. If the first forward quote (the bid or buying figure) is smaller than the second forward quote (the offer or selling figure), then it is a premium—that is, the swap rates are added to the spot rate. Conversely, if the first quote is larger than the second, then it is a discount. (A 5/5 quote would require further specification as to whether it is a premium or discount.) This procedure assures that the buy price is lower than the sell price, and the trader profits from the spread between the two prices. For example, when asked for spot, 1-, 3-, and 6-month quotes on the French franc, a trader based in the United States might quote the following:

2186/9 2/3 6/5 11/10 In outright terms these quotes would be expressed as indicated as follows:

| Maturity | Bid | Offer |

| Spot | .2186 | .2189 |

| 1-month | .2188 | .2192 |

| 3-month | .2180 | .2184 |

| 6-month | .2175 | .2179 |

Notice that the 1-month forward franc is at a premium against the dollar, whereas the 3- and 6-month forwards are at discounts. Note: The literature usually ignores the existence of bid and ask prices, and, instead, uses only one rate, which can be treated as the midrate between bid and ask prices.

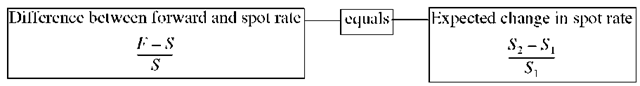

FORWARD RATES AS UNBIASED PREDICTORS OF FUTURE SPOT RATES

Because of a widespread belief that foreign exchange markets are “efficient,” the forward currency rate should reflect the expected future spot rate on the date of settlement of the forward contract. This theory is often called the expectations theory of exchange rates.

EXAMPLE 54

If the 90-day forward rate is DM 1 = $0.456, arbitrage should ensure that the market expects the spot value of DM in 90 days to be about $0.456.

An “unbiased predictor” intuitively implies that the distribution of possible future actual spot rates is centered on the forward rate. This, however, does not mean the future spot rate will actually be equal to what the future rate predicts. It merely means that the forward rate will, on average, under- and over-estimate the actual future spot rates in equal frequency and degree. As a matter of fact, the forward rate may never actually equal the future spot rate.

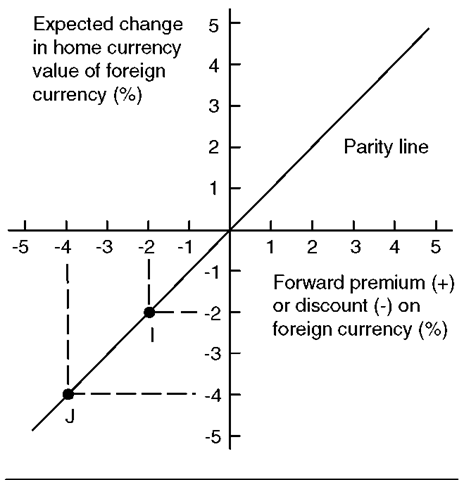

The relationship between these two rates can be restated as follows:

The forward differential (premium or discount) equals the expected change in the spot exchange rate.

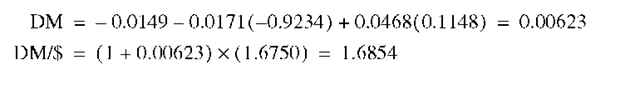

Algebraically, With indirect quotes: