Rule 3: Whenever possible, cut "in movement."

The "action cut" is the first bit of cutting lore learned by every apprentice. Excluding cuts made at the beginnings and ends of sequences and self-contained scenes, cuts to reactions or responses, and cuts involving exchanges of dialogue, the cutter should look for some movement of the actor who holds the viewer’s attention and use that movement to trigger the cut from one scene to the next. A broad action will offer the easier cut, but even a slight movement of some part of the player’s body can serve to initiate a cut which will be "smooth" or invisible.

As an example, let us take a very common sequence of cuts: In a full shot, a player enters an office, approaches a desk, and sits down in the desk chair. The full shot has established the scene’s setting, and it is now necessary to zero in on the character as he proceeds about his business, so a close shot of him at the desk is in order.

The best place to cut to the close shot is as the actor sits, and here we have three options: (1) We can leave the full shot early, as the actor reaches his chair, and show the complete action of sitting in a close shot which centers on the chair. (2) We can allow the actor to sit in the full shot, cutting to the close shot only after that action is completed. (3) We can cut somewhere between the cutting points of the first two options. For most good editors, the last would be the automatic choice.

The exact cutting point would depend on the cutter’s sense of proper timing. All exceptional editors have this sense to an exceptional degree. In our hypothetical example, the cut would probably be made at just about the point where the seat of the chair and that of the player are about to collide. (Even though that point is hidden by the desk, it can be deduced from the movement of the body, a type of deduction often required in cutting ((see p. 33)).

Cutting early would present us with some footage of the player’s midsection, not exactly an inspiring image. The late cut would carry the long shot past the viewer’s point of tolerance, however slightly. The cut at the midpoint avoids these two faults, as well as some others to be discussed later, while enabling us to take advantage of the magic of the "action cut." If there are problems with differences of position or variation in speed of movement (which sometimes occur as the result of sloppy staging), the timing of the cut might have to be modified, but the modification would be a forced compromise, not the cut of choice.

In the reverse action, also seen in virtually every film, the player rises from his chair in the close shot, and the fuller shot continues his movement.* Here the cut would probably come some 6 to 10 frames after the start of the action in the close shot. The longer shot would pick up the actor’s movement at nearly the same spot. Exact matching of position, however, might not result in the smoothest cut, for reasons to be explained shortly. Often an action overlap of 3 to 5 frames is desirable.

Contrary to common belief, the action cut does not require a measurable difference in image size. It is possible to cut from, let us say, a close-up of a player turning to his right, then have him complete his turn in another close-up, of similar size, shot from the new direction. It is even possible to move straight in, with no change in view line, from a close shot to a close-up, where the differences in size and range of movement are minimal. But this kind of cutting requires the most exquisite kind of timing, and relatively few cutters can execute it properly.

Often a cut must be made at a point where, unlike our previous examples, no broad movement is available. A player may already be seated, for instance, and the demands of the scene may call for a cut to a closer shot. In such a case, any movement—a turn of the head, for instance, or the raising of an arm as the player lifts a cup of coffee or a cigarette to his mouth—will, when precisely timed, serve to camouflage the cut. The important consideration here is that there be just enough movement to catch the viewer’s attention.

Some cutters prefer to cut just before the start of a movement or immediately after its completion, but few, if any, of the top editors follow this practice. In situations of this kind, the "static" cut cannot be intelligently rationalized, and it is excusable only if the cutter is eliminating waste footage. Then he is merely making the best of an imperfect situation. If the timing of the action, as shot, is satisfactory, the action cut will always make the smoother transition.

However, most of the cuts in a modem film, with its emphasis on dialogue, cannot be made so conveniently. A player looks off screen at something or someone, and a cut to that something or someone is in order. However, at the moment of looking, the player is usually quite still, as in the well-worn phrase, "His gaze was fixed upon. …" Obviously, no action cut is possible, yet a smooth cut can be made. But how? Or consider a dialogue scene in which two people are seated on a couch or at a table, riding in a car, or strolling down the lane talking to each other for minutes at a time, often without apparent movement, especially in their close- ups. Still, frequent cuts must be made to the speaker or to the listener’s reaction. Here, too, smooth cutting is quite possible. But how?

By creating a "diversion" of sorts, which is also the principle at work in the action cut. But before we can discuss the principle, we must build a hypothesis,* and to do that, we will examine a close relative of the action cut, one that deals with entrances and exits.

An actor exits a scene by walking out of the left side of the screen, and we follow him as he enters the next scene from the right. This is proper "screen direction," and it is always shot this way (see Figures 1 and 2). Good editing practice rules that the cut away from the first scene should occur at the point where the actor’s eyes exit the frame. The cut to the second scene should be made from 3 to 5 frames ahead of the point at which his eyes reenter the frame at the opposite side of the screen. (The cadence of his step also comes into play, but it has no bearing at this point.)

But why, when the actor appears in the second cut at the opposite side of the screen from his point of exit (which, on the wide screen, can be quite a separation), is such a cut, when properly made, completely acceptable to the viewer as a smooth, continuous action? Because his vision has been "diverted" by the apparently awkward eye movement across the width of the screen.

Figure 1

Figure 2

At the point of the cut, two things happen. First, the actor’s eyes or face, usually the viewer’s center of interest, leave the screen. Second, as a result, the viewer’s eyes, which have been following the actor’s movement, encounter the darkness at the screen’s edge. These two actions cause a reaction—the viewer’s eyes swing back toward the center of the screen, then continue to its right edge, drawn there by the entrance of the actor in the new cut. All this has happened, quite unconsciously, in a fraction of a second, not nearly long enough for the viewer to be aware of the passage of time or to notice the cut which has slipped by in the interim. For—and this is the most important factor in the process—the viewer’s eyes have been unfocused during their forced move, and he has seen nothing with clarity.

Experiments in reading long ago established that a reader’s eyes cannot focus while moving, and short pauses to focus on words or small groups of words are an essential part of the reading process. The same holds true for someone looking at the screen. As his eyes move, sharp focus is impossible. Therefore, if the cut, lasting l/24th of a second,-can be made while the viewer consumes l/5th of a second in moving his eyes, the cut will pass unnoticed. The trick is to get an audience of viewers to move their eyes en masse at the desired instant.

Hints have been around for some time. Some cutters have long been aware of one such "trick"; that is, cutting on a sharp sound—a door slam, for instance—to disguise a cut. Sharp noises cause the viewer to blink, which, as noted earlier, will take approximately l/5th of a second. The blink is the equivalent of the eye movement in the exit-entrance cut or in the action cut. The "operator" in all these cuts is the distraction which causes movement or closure of the eyes. The cutter makes his cut as the viewer’s eyes blink or are caught by the movement on the screen, much as a magician masks a move requiring camouflage by distracting the eyes of his audience with the broad sweep of his cape or a sharp movement of his "decoying" arm.

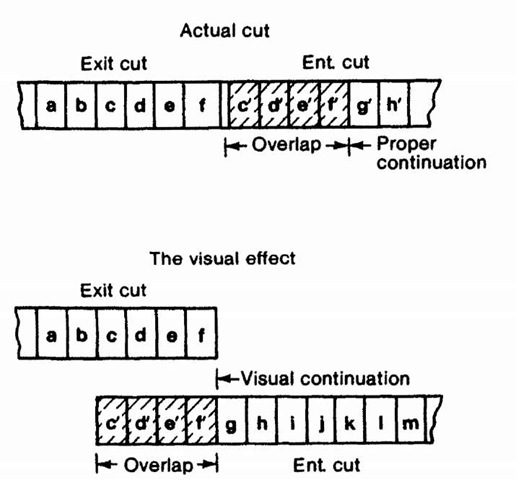

Filmmakers have often resorted to "deception" in order to deliver the "truth." The 3 to 5 frame overlap mentioned in relation to the action cut is one example of such a deception. It is best analyzed in an examination of the exit-entrance cut. The overlapping (or repeated) 3 to 5 frames at the beginning of the second cut are redundant and are meant to be so. The viewer will, in a sense, miss them, since they flash by on the screen during the fraction of a second when his eyes are moving from left to right. When his eyes are refocused, the viewer sees the proper continuation of the actor’s cross, not the short redundant overlap (see Figure 3).

If the cut were made to match exactly, what the viewer would miss during the eye movement would be frames essential to smooth action. The short hiatus would now register on the viewer’s mind as a tiny jump forward in the action.

An overlap made to accommodate the viewer’s "blind spot" is useful in most action cuts. But it is quite a subtle technique practiced by relatively few editors. Its absence from a film will hardly destroy that film for the audience. In "static" cuts, however, the subject of the next topic, the "blind spot" overlap is absolutely essential for good cutting, and no cutter should be ignorant of its proper use.

Figure 3

Most people have a strong sense of rhythm as expressed in marching, dancing, chanting, and other rhythmic activities. If this rhythm is needlessly disturbed, so is the viewer. Therefore, when cutting from one shot of a person walking to another in which the walking continues (as in an exit-entrance cut), care must be taken to make sure that the walker’s foot hits the ground (or floor) in perfect cadence. If possible, the cut should be of the same foot, but failure to match feet is not nearly as disruptive as breaking the cadence of the walking. Cutting at the instant the foot hits the floor also helps to accomplish a smoother transition.

If the shots are too close to show the legs or feet, the proper cadence can be deduced from a careful examination of the movement of the actor’s body. The rhythm of movement must be maintained even if the cut has to be shortened or lengthened by a few frames. In this case, sustaining proper rhythm is less disturbing than a slightly imperfect cut.