Cities,1 as home to over half the world’s people, are at the forefront of the challenge of climate change. Climate change exerts added stress on urban environments through increased numbers of heat waves threatening the health of the elderly, the ill, and the very young; more frequent and intense droughts and inland floods threatening water supplies; and for coastal cities, enhanced sea level rise and storm surges affecting people and infrastructure (Figure 1.1) (IPCC, 2007). At the same time, cities are responsible for a considerable portion of greenhouse gas emissions and are therefore crucial to global mitigation efforts (Stern, 2007; IEA, 2008). Though cities are clearly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, they are also uniquely positioned to take a leadership role in both mitigating and adapting to it because they are pragmatic and action-oriented; play key roles as centers of economic activity regionally, nationally, and internationally; and are often first in societal trends. There are also special features of cities related to climate change. These include the presence of the urban heat island and exacerbated air pollution, vulnerability caused by growing urban populations along coastlines, and high population density and diversity. Further attributes of cities specifically relevant to climate change relate to the presence of concentrated, highly complex, interactive sectors and systems, and multi-layered governance structures.

The Urban Climate Change Research Network (UCCRN) is a group of researchers dedicated to providing science-based information to decision-makers in cities around the world as they respond to climate change. The goal is to help cities develop effective and efficient climate change mitigation and adaptation policies and programs. By so doing, the UCCRN is developing a model of within- and across-city interactions that is multidimensional, i.e., with multiple interactions of horizontal knowledge-sharing from the developing to developed cities and vice versa. The UCCRN works simultaneously by knowledge-sharing among small to mid-sized to large to megacities as well. Free-flowing multidimensional interactions are essential for optimally enhancing science-based climate change response capacities. The temporal dimension is also critical – the need to act in the near term on climate change in cities is urgent both in terms of mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions and in terms of climate change adaptation. The UCCRN is thus developing an efficient and cost-effective method for reducing climate risk by providing state-of-the-art knowledge for policymakers in cities across the world in order to inform ongoing and planned private and public investments as well as to retrofit existing assets and management practices.

Contributions to climate change and cities

There are several ongoing efforts that focus on climate change and cities. On the institutional side, ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability has played a major role in encouraging mitigation efforts by local governments around the world.

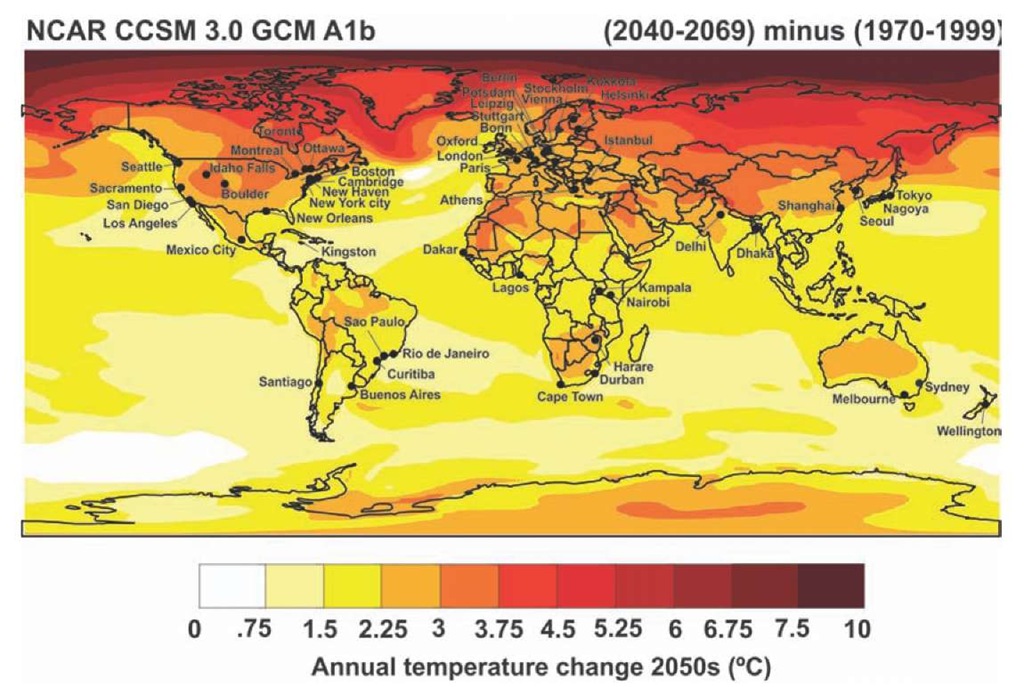

Figure 1.1: Cities represented in ARC3 and 2050s temperature projections for the NCAR CCSM 3.0 GCM with greenhouse gas emissions scenario A1b.

The UN-HABITAT has started a cities and climate change program, as has the World Bank and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). On the research side, the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) has focused on community aspects of climate change vulnerability in developing cities, and the World Bank has sponsored a set of research studies for the Fifth Urban Research Symposium held in Marseille in June 2009. The Global Report on Human Settlements 2011 of UN-HABITAT is focused on cities and climate change.

Focus on the urban poor

One of several major foci of these efforts is the developmental needs of the urban poor. In urban areas, inequities among socioeconomic groups are projected to become more pronounced as climate change progresses.For example, the urban poor are less able to move from highly vulnerable locations in coastal and riverine areas at risk of enhanced flooding. This will lead to changes in the spatial distribution and density of both formal and informal urban settlements. Factors that affect social vulnerability to climate change include age, lack of material resources, access to lifelines such as transportation and communication, and lack of information and knowledge. As warmer temperatures extend into higher latitudes and hydro-logical regimes shift, some vector-borne diseases may extend their ranges, either re-emerging or becoming new problems. Water-borne diseases may shift ranges as well due to changes in water temperature, quantity, and quality in future climates. Such changes can cause serious consequences, especially in densely populated informal settlements in cities in developing countries.

Intersection of climate change and disaster risk reduction and recovery

A related focus is on the intersection of climate change and disaster risk reduction and recovery. Climate change and its effects have the potential to increase exposure to a range of urban risks, and in turn influence how disaster reduction strategies need to be conceived and executed by urban decision-makers. Current efforts by both the climate change and the disaster risk reduction communities are focused on identifying pathways and opportunities for integrating climate change adaptation strategies and disaster risk reduction activities into the daily programmatic activities of a broad range of stakeholder agencies in cities. Disaster- and hazard-related organizations as well as stakeholders who manage risk in other agencies will need to take on these challenges.

Many impacts of climate change in cities, especially in the short and medium term, will be felt in the form of enhanced variability and changing frequency or intensity of extreme events. These will often be considered "disasters." As disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation are beginning to converge, there is the potential for them to be largely managed as one integrated agenda. There is not, however, complete overlap between the two fields. One difference is that disaster risk reduction covers geophysical disasters, such as earthquakes, which do not overlap with climate risk.

While climate risk is certainly connected with the increased likelihood of damaging extreme events, climate change is also conceptualized as an emerging public policy issue relating to slow transitions in many urban sectors, ranging over water supply and sanitation, public health, energy, transportation, and migration, among others, which demands response within existing management cycles and planning activities. A central challenge for cities is not only to define the links between climate change and adaptation and disaster risk reduction with respect to extreme events but also with respect to these other climate change policies, which if mismanaged could aggravate vulnerability.

In order for cities to develop effective and resource-efficient integrated strategies for climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction, the two efforts need to be connected wherever possible with ongoing policies and actions that link the two from both directions. The climate change adaptation community of researchers and stakeholders emerged in relative isolation from long-standing disaster management policy and practices. Cross-fertilization is now being encouraged between these two groups to take advantage of already-recognized best management practices and to reduce redundancy of efforts, which cities cannot afford (IPCC, 2011). Instead, disaster risk reduction strategies and/or adaptation strategies can contribute to reduction of poverty levels and vulnerability, and promote economic development and resilience in an era of increasing climate change.