ORDER

Anseriformes

FAMILY

Anatidae

GENUS & SPECIES

KEY FEATURES

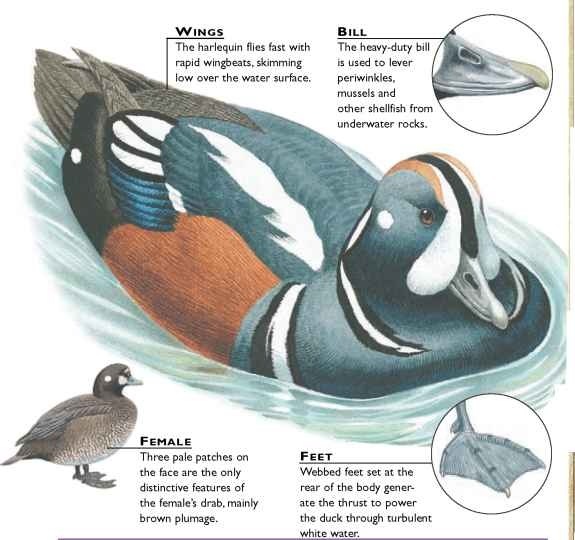

Spends almost all its life in or near white water, swimming against strong currents with skill Nests on fast-flowing rivers at the water’s edge: the chicks leap in and swim as soon as they hatch Moves to rocky coasts in winter, riding the surf and diving down to pry shellfish from the seabed

WHERE IN THE WORLD?

Five major populations exist: in Alaska and northwest Canada, Labrador region of eastern Canada, southern Greenland, Iceland and northeastern Siberia

LIFECYCLE

Enduring a rough-and-tumble life amid the wild, bitterly cold rivers and seas of the far north, the tough harlequin duck relies on its masterful swimming and diving skills.

HABITAT

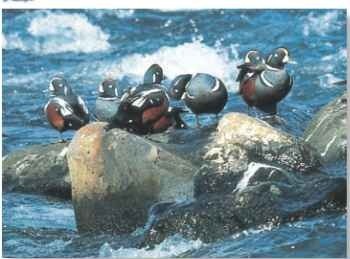

A White-water rafting A group of males clings to boulders in midstream.

Wet feet

The harlequin duck rarely moves far from water.

The harlequin duck inhabits the turbulent, almost-freezing waters high in the northern hemisphere. It spends most of spring and summer on swift-flowing streams and rivers in upland areas, sometimes at high altitudes in Iceland and the Rocky Mountains of North America. It seeks watercourses rich in animal life, such as spring-fed rivers and outlets into lakes; hollows under rocks provide plentiful nest sites.

In fall, the harlequin duck flies downstream to the sea, remaining close to the shore. Shunning sheltered bays, it prefers exposed headlands and rocky beaches under steep cliffs. In April, it migrates upstream to breed.

BEHAVIOR

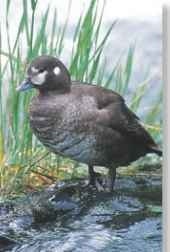

A Taking a break An energetic lifestyle demands frequent rests.

When it moves upstream in spring, the duck travels by both flying and swimming. It rides high in the water, making a bobbing movement of the head with each stroke of its legs. In the rushing torrents that it inhabits in spring, the rocks are always wet, but the duck can climb the slippery surfaces with ease. It can also walk underwater along the riverbed by facing into the current, closing its wings and thrusting with its legs. Outside the breeding season, the harlequin lives in flocks of up to 50 birds in the Atlantic and in larger gatherings in the Pacific.The birds form “rafts” on the water and fly low over the waves in dense flocks.

FOOD & FEEDING

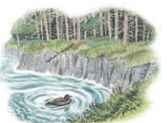

Along the streams and rivers where it breeds, the duck dives repeatedly to a depth of 3-7′, searching underwater rocks and gravel for food. It hunts larvae of caddis flies, blackflies and mayflies, also taking freshwater shrimps and beetle larvae. The harlequin feeds in tight-packed flocks in winter, diving through surf in groups to tear periwinkles, mussels and other shellfish from rocks on the seabed. Sometimes, it also preys on small crabs and fish.

The duck feeds rapidly Most dives last 15-18 seconds, but it can stay submerged for twice as long. It dives from the surface or rocks. In shallows, it dips its head under while wading or swimming.

A Plunge pool

The harlequin duck feeds by diving and “head-dipping.”

WATER OF LIFE

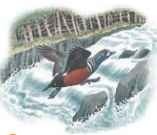

Round the bend…

The harlequin duck flies fast and low, following every twist and turn in a river’s course to avoid crossing land.

Against the flow…

To travel upstream, the duck makes use of eddies, backwaters and slack water near the bank.

Uphill struggle…

White water is no obstacle.The duck negotiates rapids by fluttering and pattering over the water surface.

Safe and sound

When it’s time to nest, a female chooses a site safe from flooding hidden in bankside vegetation.

The harlequin duck is named after the male’s bold pattern of stripes and spots, reminiscent of the costumes worn by the human “harlequin”: a clownlike figure in traditional comedies.

Although it’s sociable with others of its kind, the harlequin rarely mixes with ducks of other species.

Harsh winters or severe storms may drive harlequin ducks south, as far as Hawaii, Florida and Britain.

CONSERVATION

Human activity has had little impact on this duck, as it rarely encounters humans in its mountainous breeding areas or the isolated coasts where it winters. With a world population of over one million birds, the harlequin isn’t in any danger. Its eggs were once collected in Iceland for export to wildfowl collections, but it’s now protected. However, pollution, such as oil spills, in its wintering areas may yet become a threat.

BREEDING

Harlequins form pairs in December, when the birds are still living in winter flocks. Several males display to one female, uttering high-pitched whistles and squeals. Toward the end of April, the paired ducks move inland, but courtship displays continue through the first part of the breeding season, and the male must defend his mate from other males. Once she has laid her clutch of 5-7 eggs, he deserts her and takes no further part in the rearing of the young.

The female lays her eggs in the last week of May or the first week of June in a simple nest — a well-concealed depression lined with leaves and twigs. After an incubation period of four weeks, the downy chicks hatch.They’re well developed, capable of walking, swimming and feeding within a very short time, but their mother broods them at night while they’re small. Young fledge after 35-42 days, then the female leads them to the sea and independence.

Pairs form in late winter and spring but separate when the female begins to incubate her eggs.

Profile

Harlequin Duck

A master swimmer on rushing torrents and crashing ocean waves, the harlequin duck drives its buoyant, compact body with strong, webbed feet.

CREATURE COMPARISONS

The male black, or common, scoter (Melanitta nigra) has a glossy black plumage, with only a yellow splash and knob on its bill.The female has a drab, gray-brown plumage to camouflage her when she’s incubating eggs. She lacks the yellow patch on the male’s bill and the “knob” at its base.

The black scoter is larger than the harlequin. It breeds on the tundra of northern Eurasia and North America, alongside the harlequin in Iceland and Alaska.

| VITAL Weight |

STATISTICS 1-1.5 lbs. |

| Length | 1-1.5′ |

| Wingspan | 2-2.3′ |

| Sexual Maturity | 2 years |

| Breeding Season | May-August |

| Number -of Eggs | 5-7 |

| Incubation Period | 27-29 days |

| Fledging Period | 35-42 days |

| Breeding . Interval | 1 year |

| Typical Diet Lifespan |

Mussels, other shellfish; aquatic insects, crustaceans; small fish Unknown |

RELATED SPECIES

• Known as wildfowl or waterfowl, Anseriformes includes the 3 species of screamer and all ducks, geese and swans. Screamers (noisy, gooselike birds from South America) I belong to the Anhimidae family. All other wildfowl are in the Anatidae family. The harlequin duck is the only member of the genus Histrionicus, but shares features with eiders, goldeneyes, scoters and the long-tailed duck.