Thebes, royal funerary temples

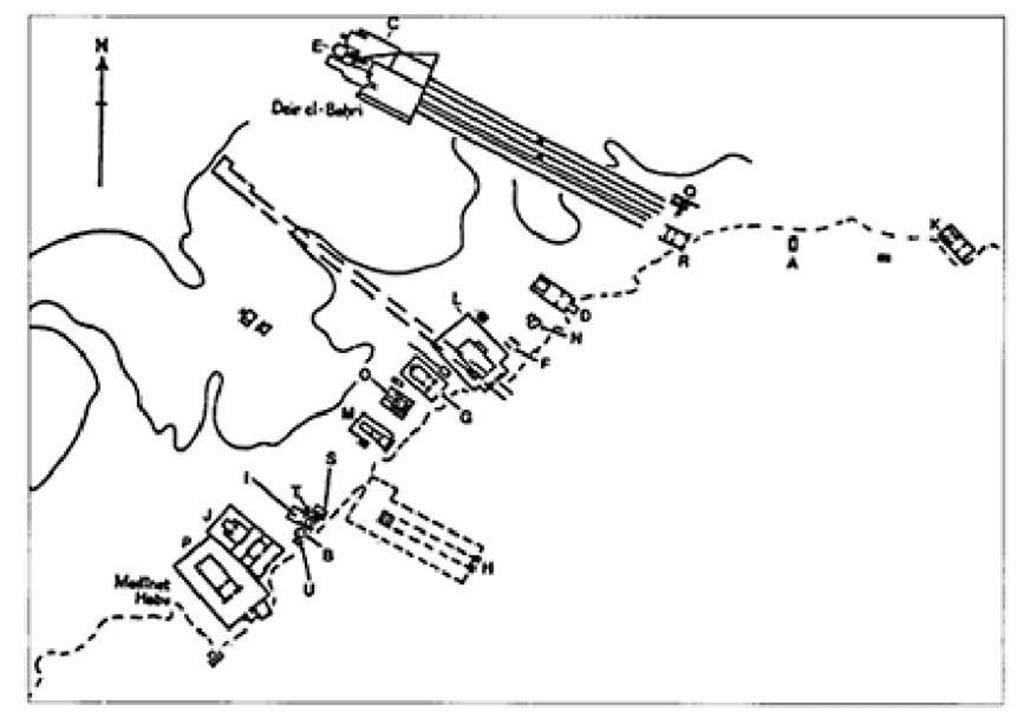

During the New Kingdom royal funerary temples were built apart from the kings’ tombs in the Theban hills and erected on the strip of low desert that separated those hills from the cultivation on the west bank of the Nile opposite the city of Thebes (modern Luxor). There were roughly twenty royal funerary foundations built in West Thebes during the approximately 500 years of the New Kingdom. These were formally described as "the mansion of millions of years of King X’ followed by an epithet, for example, "United with Eternity." More often, this lengthy name was shortened to "the mansion" followed by the king’s name and/or the temple’s distinctive epithet or a local nickname. It is thus not always possible to discern whether such a name describes a true mortuary temple. Temples for a number of rulers during this period remain unattested: some may have never been built, while others were either destroyed, usurped by later rulers or remain to be discovered. In the following checklist, letters in parentheses refer to locations on the map.

18th Dynasty

Ahmose: not preserved.

Amenhotep I: identity uncertain. A temple (A), named "Most Established of Place," was dedicated to the king and his mother, Ahmose-Nofretari. It was found in front of the Dra’ Abu el-Naga hills, but it is not clear that this structure must be the king’s mortuary temple (as opposed to that of his mother).

Tuthmose I: the building, attested in contemporary sources and named "United with Life," is not preserved. It must have been located at the south end of the site, near Medinet Habu.

Tuthmose II (B): named "Receiver of Life," and located between the hill of Qurnet Murai and Medinet Habu.

Hatshepsut (C): named "Holiest of Holies" and located inside the bay of Deir el-Bahri beside the 11th Dynasty temple of Mentuhotep I, which may have influenced its unusual terraced design. A causeway led to a valley temple, now poorly preserved.

Tuthmose III (D): named "Gifted with [?] Life," located opposite the northern end of the Sheikh Abd el-Qurna hill. The pylon in front of the temple, along with parts of the enclosure wall (both made out of mudbrick), can still be seen, but the stone temple inside has been reduced to fragments, although the ground plan has been traced.

Amenhotep II (F): located between the Ramesseum and Tuthmose III’s mortuary temple; given the same name as Tuthmose II’s mortuary temple, "Receiver of Life." The ruins, poorly preserved, are now covered by modern debris.

Tuthmose IV (G): located south of the Ramesseum. The ground plan has been reconstructed, but the building itself is destroyed.

Amenhotep III (H): located east of Qurnet Murai and known locally as Kom el-Hetan. Named "[Mansion] which Receives Amen and Elevates his Beauty," the complex was set apart by the great size of its original grounds and the vast number of statues, representing both the king and numerous divinities, which it once housed. Along with the misnamed "colossi of Memnon" that still mark the now vanished entrance to the temple, remains of a number of other statues can still be seen above ground. The only architectural remnant of any size is near the back of the temple, where a great "sun court" was surrounded with columned porticos (like those of Luxor temple) adorned with statues of the king. The excavation of the site is still only partly reported in print. South of Amenhotep III’s foundation was the much smaller mortuary temple (I) which the king had built as an extraordinary honor for his most favored contemporary, the scribe Amenhotep son of Hapu, who by late antiquity would be revered as a local saint.

Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten): built no mortuary temple at Thebes, but the "Mansion of the Solar Disc" at el-Amarna is believed by some scholars to be the mortuary temple that would be expected to accompany the tomb which the king built for himself at this site. Structures called "sunshades," which the king had built for his wives, daughters and mother, appear to have functioned as mortuary chapels for them.

Smenkhkare and/or Nefernefruaten: neither preserved nor clearly attested. A "Mansion of Ankh-kheprure in Thebes" mentioned in a contemporary graffito has been assumed to be a royal mortuary temple, but the name might as well belong to a foundation that was planned within the Karnak temple on the east bank.

Tutankhamen: a mortuary temple was surely planned for this king, but neither the building’s name nor its location is known. It may have lain in the area of Medinet Habu, perhaps on (or near) the site used by his successors.

Ay (J): began his mortuary temple (named "Most Established of Monuments") north of the 18th Dynasty temple to Amen at Medinet Habu, but the building remained unfinished at his death.

Horemheb (J): took over his predecessor’s mortuary temple site and redesigned its plan. The building is ruined, but a careful excavation of the site yielded much that sheds light on both phases of its history.

19th Dynasty

Ramesses I: see below.

Seti I (K): the so-called "Qurna temple" is located opposite the north end of the hills at Dra’ Abu el-Naga and was named "Effective is Seti Merneptah in the Estate of Amen." It included a cult chapel for Ramesses I, who reigned too short a time to build a temple for himself, and it was finished by Seti’s successor, Ramesses II.

Ramesses II (L): named "United with Thebes," but popularly known as the "Ramesseum," Ramesses II’s funerary temple is located opposite Sheikh Abd el-Qurna. It was the most ambitious building of its type since Amenhotep III. Like the latter’s temple, the Ramesseum was a tourist attraction during late antiquity (Diodorus I 47-9) but it was less extensively quarried. The central part of the building is substantially intact.

Merenptah (M): located between the Ramesseum and Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple, it was reduced to its foundations before modern times. Excavations have revealed that much of the stone used in its construction derived from the adjoining complex of Amenhotep III. The remains are currently being studied for publication by the Swiss Archaeological Institute.

Amenmesse: not preserved. His successor may well have destroyed or usurped it.

Seti II: although mentioned on wine jar dockets found at the temple of Siptah, the building itself has not been rediscovered.

Siptah (N): located between the temples of Tuthmose III and Amenhotep II, the building is now reduced to its foundation trenches.

Tawosret (O): located between the temples of Merenptah and Tuthmose IV, the building was larger than Siptah’s but was just as completely destroyed.

20th Dynasty

Sethnakht: since no cult rooms for this short-reigning king were included in his son’s mortuary temple, Sethnakht probably owned a foundation of his own; but no trace of the building has been found.

Ramesses III (P): named "United with Eternity," but commonly known as Medinet Habu, this is the southernmost, and best preserved, of the New Kingdom mortuary temples. Ramesses IV: this king began construction on three temples in West Thebes: two (Q, R) respectively north and south of the entrance to the bay of Deir el-Bahri (only foundation deposits of this king, with many blocks reused from earlier temples); and another, smaller temple (S) north of Medinet Habu. Since work on the very large temple near the hill of Asasif (R) was continued by Ramesses V and VI, a reasonable if not conclusive case can be made that Ramesses IV began this structure as his own mortuary temple but abandoned it in favor of the smaller building near Medinet Habu. Ramesses V and Ramesses VI: it is assumed that Ramesses V continued his predecessor’s Asasif temple (R), and that it was usurped from him by Ramesses VI, who also took over the tomb Ramesses V had begun for himself in the Valley of the Kings. Ramesses VII-XI: no mortuary temples are attested even though all but the ephemeral Ramesses VIII had tombs in the royal valley. Hard economic times and the increasing withdrawal of royal patronage from southern Egypt during the late 20th Dynasty may both have inhibited temple building, but it seems incred-ible that no provision was made for the cults of these kings at Thebes. A possible candidate for one of these "lost" temples might be the small building to the north of Tuthmose II’s temple near Medinet Habu (T); but although it was constructed later than the adjoining 18th Dynasty temple of Amenhotep son of Hapu on which it encroached, there is no solid evidence for its date or purpose.

Design and function

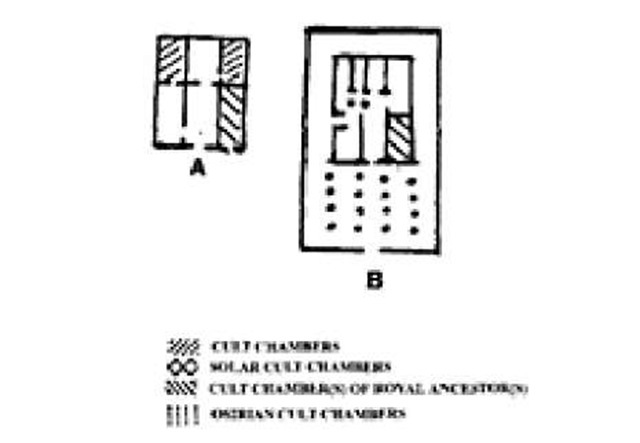

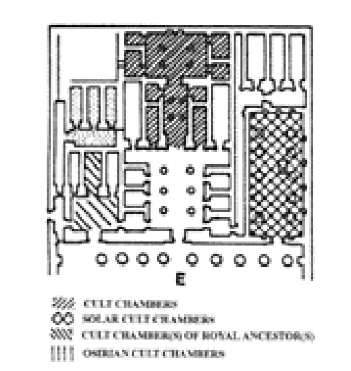

The earliest mortuary temples of the New Kingdom were small buildings that seem to follow the layout of contemporary cult temples in West Thebes. The plan of Tuthmose II’s temple, for example, is strikingly similar to that of the 18th Dynasty temple at Medinet Habu. In both the chapel of the royal cult is isolated at the northeast corner of the building, separate from the other, larger suite(s) which, at Medinet Habu, were dedicated to various forms of the god Amen. By analogy, we may speculate that the predominant divine presence in Tuthmose II’s mortuary temple was also that of Amen, as it would be in all later mortuary temples of the New Kingdom.

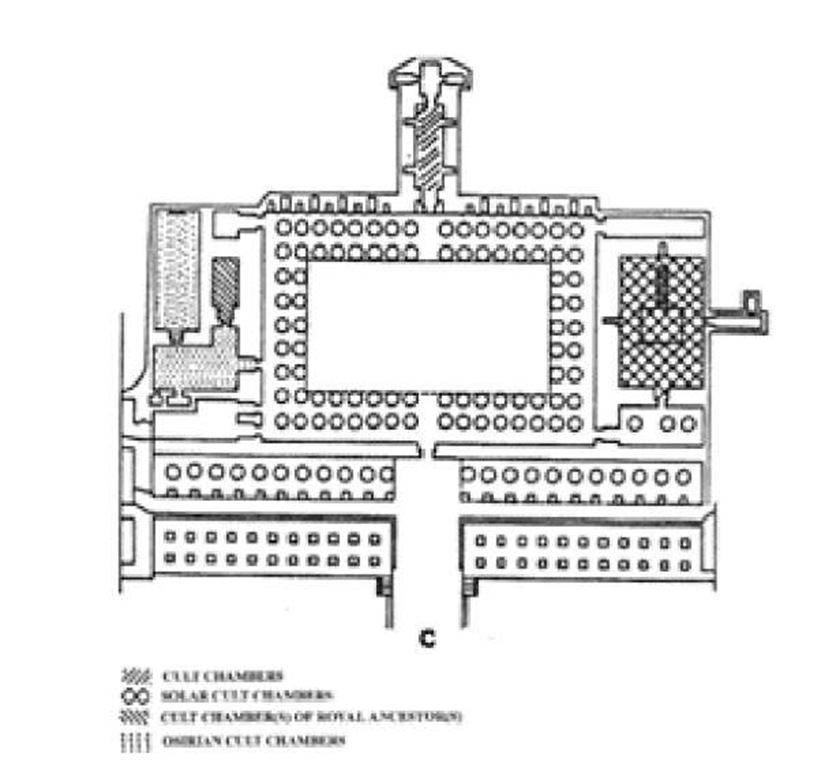

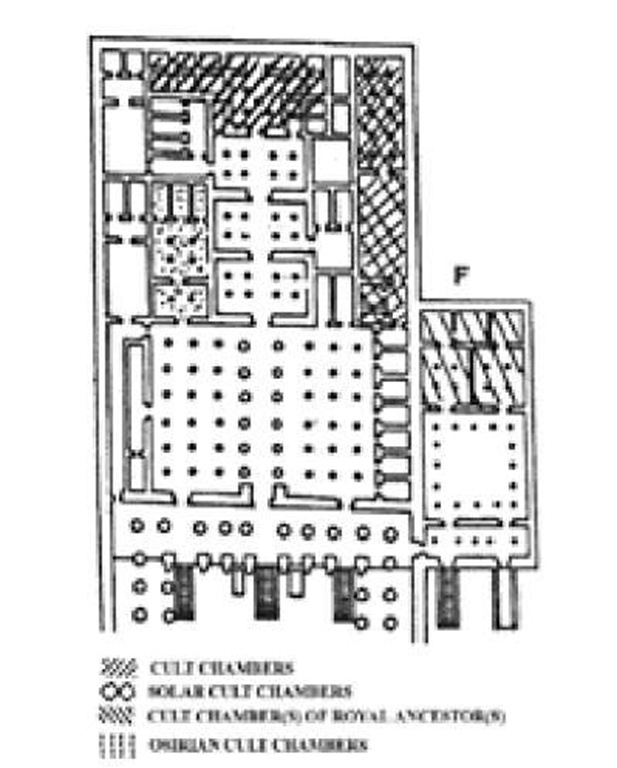

What would become the classic plan is first revealed in the temple of Hatshepsut, where the chambers of the Osiride mortuary cult are shifted to the south side of the inner temple, balanced by a suite dedicated to the solar resurrection on the north side, while Amen’s cult chambers lie between these two units along the center of the building’s axis.

Figure 115 Royal funerary temples in West Thebes

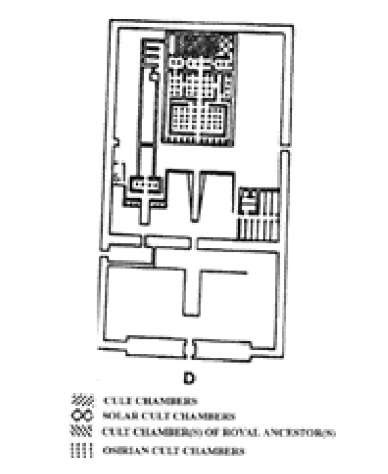

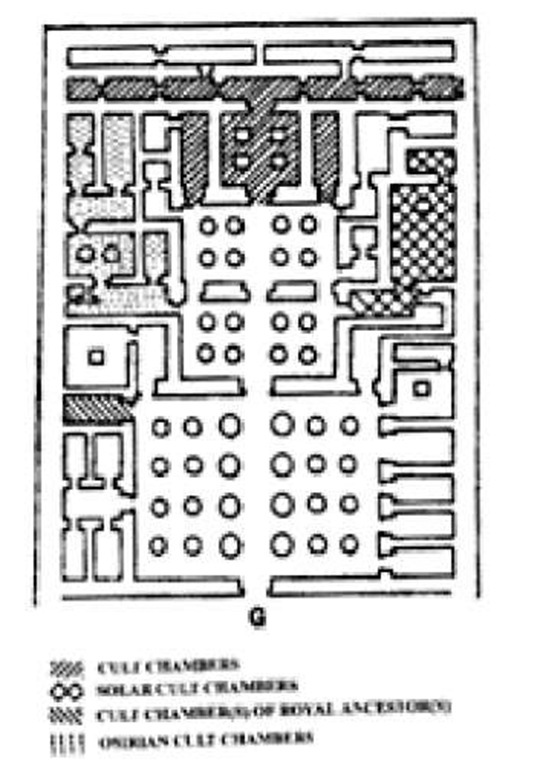

With slight variations, this layout was continued throughout the New Kingdom: compare the temples of Tuthmose III, Ramesses II, Merenptah and Tawosret. The most variable elements of the plan were the solar suite (which may have been omitted or located elsewhere, as in Horemheb’s temple); and the cult room(s) of the royal ancestors, which nonetheless always lay somewhere in the Osiride region along the south side of the building (e.g. Seti I and Ramesses III).

These arrangements reflect the complex divine identity of the pharaoh. The solar suite reflects the afterlife as portrayed in the royal tombs, where the king joined the circuit of nature by joining the sun god Re on his eternal rounds. This celestial identity was balanced by the pharaoh’s transformation into Osiris, the god who had conquered death and ruled as king of the underworld. At Thebes, moreover, the fusion of royal ideology with the theology of Amen (who had also acquired a solar identity as Amen-Re) made the pharaoh both the son of and a manifestation of this deity: in this mortuary temple, each king was recognized as the resident form of the god (e.g. at Medinet Habu the divine Ramesses III was "Amen-Re United with Eternity," while his ancestor Ramesses II was "Amen-Re United with Thebes"). In fully developed temples of the later New Kingdom, the king’s ceremonial presence under his various forms was maintained by a series of "false doors," which communicated symbolically with the king’s tomb and with other parts of the temple. At Medinet Habu, for example, false doors are found not only at focal points in the suites dedicated to Osiris and Amen, but also in the palace, a small building attached to the south wall of the temple, which served both as a rest house during royal visits to the site and as an eternal dwelling for the king’s spirit.

The royal mortuary and cult temples must have formed an imposing "kings’ row" at the edge of the Theban necropolis during the New Kingdom. Few are substantially extant today. Some remained unfinished, functioned for only a short time before the ruler’s cult lapsed or suffered natural damage. Most of the damage is manmade, however, and resulted when blocks were quarried from these buildings for use in projects by later rulers. Such depredations, continued as sporadic pilferage by the inhabitants of West Thebes, have reduced most of the New Kingdom mortuary temples to the barest foundations. Those that survived best were reused by later generations for their own purposes. Buildings inside the complex of Ramesses III, for example, were integrated into the town of Djeme that grew up around them and thus survive in remarkably good condition. Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahari, which was not as badly damaged by falling rock as its neighbor just to the south, served as the foundation for a Christian monastery. A combination of local celebrity and reuse seems also to have rescued large parts of Seti I’s and Ramesses II’s temples from destruction; although Amenhotep III’s temple was on the whole less fortunate, the great size, hardness and mystique of its quartzite colossi have conspired to preserve them, battered but still largely intact, into the present day.

Thebes, Senenmut monuments

The Theban monuments of Senenmut, Great Steward of Amen during the coregency of Hatshepsut and Tuthmose III, are not only large in number but significant for the cultural and historical light they shed on the early 18th Dynasty. In addition to an impressive tomb split into two architecturally separate components, Senenmut dedicated no fewer than eighteen statues and a land donation stela in the area of ancient Thebes. As a group, these monuments provide crucial information on the meteoric career of Senenmut, the history of the coregency of Hatshepsut and Tuthmose III and its aftermath, the nature of contemporary private tomb architecture, and the development of statue types during the early 18th Dynasty. Despite this wealth of documentation, however, the circumstances surrounding the death of Senenmut and the posthumous persecution of his name have never been satisfactorily explained.

West bank monuments

Because of its unusual architecture and the circumstances of its discovery, Senenmut’s tomb possesses two numbers in the catalog of the Theban necropolis. The funerary chapel of Senenmut was built near the summit of the Sheikh Abd el-Qurna hill and was well known in both antiquity and in recent times, when it was assigned number 71 and assumed to comprise his tomb in toto. The wall paintings were copied in the 1920s by Norman de Garis Davies and clearance was carried out in 1930-1 by Herbert Winlock, both of the Metropolitan Museum’s Egyptian Expedition. Carved for the most part in layers of loose shale, Senenmut’s funerary chapel is the largest of its kind prior to the reign of Amenhotep III, but is otherwise typical, in both its architecture and decoration, of contemporary Theban chapels. The transverse passage was lit by eight rectangular windows set into the fagade, and its roof was supported by a row of eight pillars. The separate aisles formed by the pillars were distinguished by different ceilings: flat, curved, gabled and shrine-shaped. The long axial corridor leading directly into the hill ended in a false door stela (now in Berlin, no. 2066) and a rough-cut niche above, originally lined with carved and painted relief blocks.

Because of the poor quality of the bedrock, the decoration was executed almost entirely in paint on a plaster ground, supported by thousands of small limestone chips embedded in structural plaster. Much of this delicate painted layer has now collapsed, leaving only hints of the magnificence of the original decoration. A number of scenes can still be recognized: a tribute scene featuring a procession of Aegean men carrying their foreign wares; a depiction of the "Abydos pilgrimage," showing the deceased en route to visit the mythical tomb of Osiris; the funeral procession, in which the sarcophagus and personal belongings of the deceased are carried to his tomb; the funeral banquet and a long menu list of offerings; and the hauling of statues sheltered under canopied shrines.

On the hillside above the niched fagade of the tomb, a rock-cut statue of Senenmut was begun but never finished, perhaps because of a fissure in the rock. In front of the fagade, a large artificial terrace was built to provide a wide entrance forecourt. Under this terrace William Hayes and Ambrose Lansing of the Metropolitan Museum’s Egyptian Expedition excavated in 1935-6 the intact burials of Senenmut’s parents, Ramose and Hatnefer, interred with six other poorly wrapped mummies, apparently all family members. Six other burials, all of the early 18th Dynasty, were found in the loose scree of the hillside, as well as deposits of hunting weapons and the coffins of a horse and an ape.

In January 1927, Herbert Winlock discovered a descending passage in the floor of the Asasif Valley northeast of the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri, leading to a chamber decorated with funeral texts and vignettes depicting Senenmut. This "second" tomb, never finished in antiquity, was given number 353 and was initially assumed to be a separate tomb that Senenmut began late in his life but which was abandoned before its completion. In fact, Tomb 353 is simply the burial apartment that complements the separate funerary chapel (Tomb 71) on Sheikh Abd el-Gurna. Arranged around a carved false door stela, several topics from the Book of the Dead adorn the western side of the chamber, most pertaining to the specific topography of the netherworld. The eastern side of the room is decorated with the texts of two long funerary liturgies, unique for the New Kingdom. The ceiling bears the earliest known astronomical representation of the night sky, comprising a star clock, the northern constellations, and the twelve lunar months and their associated deities. Situated near the tomb were five foundation deposits containing model tools and objects, some of which bear the names of Senenmut or Hatshepsut. Sealed at the time of its abandonment, the tomb was initially buried by broken statuary and debris from Hatshepsut’s temple at the time of her posthumous persecution. The area was later used as a dump for votive offerings discarded from the several temples at Deir el-Bahri and as a repository for Late period embalming caches.

Figure 116 A, Medinet Habu, 18th Dynasty temple; B, Funerary temple of Tuthmose II

Senenmut’s quartzite sarcophagus was dis-covered in the vicinity of his funerary chapel, Tomb 71, smashed into more than a thousand fragments. Reconstruction reveals that in its material, its oval shape and its choice of texts the sarcophagus is roughly similar to contemporary royal sarcophagi, although its interior decoration consists largely of a version of topic 125 of the Book of the Dead. The sarcophagus was unfinished and never used.

Figure 117 Funerary temple of Hatshepsut

Figure 118 Funerary temple of Tuthmose III

Figure 119 Funerary temple of Seti I

Figure 120 Funerary temple of Ramesses II

Two statues of Senenmut have been found at Deir el-Bahri, a fragmentary one by Edouard Naville in 1894 during his clearance of Hatshepsut’s temple (P^-fi™ ), and a sistrophorous sculpture (the owner, kneeling, presents a large votive sistrum) by the Polish-Egyptian Mission in 1963 at the adjacent temple of Tuthmose III

Unusually for a private official, Senenmut appears in several places in the formal reliefs of Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple. As the inscriptions state, this signal favor was granted by the queen.

East bank monuments

In the precinct of the Montu temple at North Karnak, a stela of Senenmut was found by Louis Christophe in the late 1940s. The text describes a donation of land made by Senenmut to establish endowments for certain institutions within the domain of Amen at Thebes, the land in question having been given to Senenmut earlier by the young Tuthmose III.

Figure 121 Funerary temple of Ramesses III

The thirteen statues of Senenmut from the east bank of Thebes represent several of the earliest types of sculpture that are later attested throughout much of the 18th Dynasty and even into the New Kingdom, including sistrophorous, naophorous (a votive naos, or shrine, is presented), "tutor" statues (the owner is shown with his or her royal ward) and rebus statues (a hieroglyphic rebus of a royal name or emblem is presented). Four statues of Senenmut were unearthed in the great cachette at Karnak that was found by Georges Daressy in 1904 (Cairo CG 42114, 42115, 42116, 42117). The body of a fifth (Cairo JdE 47278), a block statue of Senenmut and Neferure, Hatshepsut’s only daughter, was discovered by Maurice Pillet in 1922 to the south of Pylon 9. This statue was reused as a building block in Late period foundations; the head and other fragments, however, came to light in 1970-1 in an ancient tree enclosure near the temple of Montu in North Karnak, where it was probably erected originally.

The temple of Mut at Karnak has also yielded a block statue of Senenmut (Cairo CG 579), which recounts the construction projects he undertook there; it was discovered by Margaret Benson and Janet Gourlay in 1896 in the southwest corner of the temple enclosure. A quartzite rebus statue of Senenmut (Cairo JdE 34582) was found in 1900 at the temple of Luxor. Two other sculptures, presently housed in the Sheikh Labib and Karakol magazines at Karnak, were apparently dedicated in the precinct of the temple of Amen.

Other monuments

Several noteworthy monuments belonging to Senenmut have been identified outside the Theban area. The largest is a rock-cut shrine carved into the sandstone bluffs of the western Gebel el-Silsila quarries, from which so much stone was extracted for the construction of the temples of Thebes. Like many of his contemporaries who supervised work there, Senenmut dedicated a small chapel in honor of himself, the gods of the First Cataract region, and the reigning king; in this case, Queen Hatshepsut, prior to her assumption of kingly titles but nonetheless portrayed here as a man. At Aswan, a graffito commemorates Senenmut’s efforts in quarrying two granite obelisks during the period Hatshepsut was acting as regent for the young Tuthmose III. Finally, another commemorative stela at the temple of Hathor at Serabit el-Khadim in southern Sinai, dated to year 11 of Tuthmose III and Hatshepsut, depicts Senenmut standing behind his former ward, the princess Neferure.