Marsa Matruh

The modern resort city of Marsa Matruh (Graeco-Roman Paraitonion, longitude 31°21′ N, 27°14′ E) on the northwest Mediterranean coast is situated between Alexandria, 290km to its east, and the Libyan frontier town of el-Salloum, 210km to its west. Geographically important in antiquity, Matruh’s protected natural harbor and adjacent lagoon systems provided the only reliable haven for mariners between Alexandria and Tobruk (ancient Antipyrgos in eastern Libya), a distance of some 600km.

Paraitonion was allegedly founded by Alexander the Great at the time of his visit to Siwa Oasis in 331 BC, but there is archaeological evidence of some kind of settlement in trading contact with Greece as early as the eighth century BC. Prior to that, excavation has shown that at least one sector of the Matruh area was utilized in the fourteenth and perhaps into the thirteenth century BC as a way-station for Late Bronze Age (LBA) mariners whose home base was probably Cyprus. Designated "Bates’s Island" after the American archaeologist Oric Bates, who surveyed Marsa Matruh for Harvard’s Peabody Museum in 1913-14, the settlement occupies a small (135x55m) sandy islet at the east end of the first of the five saltwater lagoons that stretch eastward from Matruh’s harbor. No other sites similar to Bates’s Island have come to light in the region, but the island’s diminutive size argues that additional foreign settlements may have been established elsewhere here. The presence of a Ramesside fortress at nearby Umm el-Rakham raises the possibility that pharaonic use of the harbor area existed perhaps as early as the 19th Dynasty. The likeliest location for such development would have been in the coastal plain directly south of the harbor, covered today by the modern city and thus inaccessible for excavation.

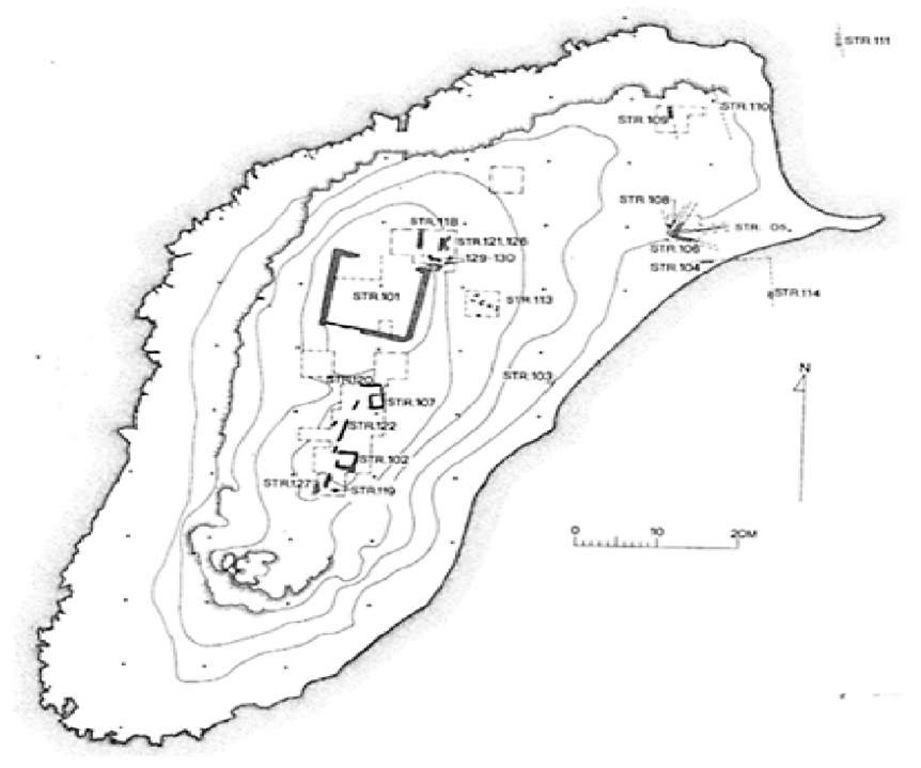

Figure 62 Plan of structures on Bates’s Island, Marsa Matruh

No early artifacts were retrieved on Bates’s Island below 2.5m above sea level, seemingly because of the rise in water level throughout the lagoon system during the fourteenth century BC, and its Late Bronze Age occupation appears to have been on the island’s low sandstone ridge. This implies that the insular setting was substantially smaller than it is today but better protected.

The island’s LBA architectural remains are poorly preserved. The upper levels of the rubble walls were entirely demolished for reuse in later Graeco-Roman buildings, as well as in more recent times, when a 12.5×12.9m shelter was built in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century that eventually housed sponge-divers. Much of the island’s imported LB A pottery was found inside or near the "Sponge Divers’ House," which today separates clusters of LBA remains to its north and south, suggesting that a single, uninterrupted line of small attached rooms and open enclosures covered much of the island’s longitudinal north-south spine during the LBA period.

North of the Sponge Divers’ House are structural remains, consisting mostly of sections of isolated walls. Associated pottery, including the island’s broadest selection of all classes of LBA pottery (with the exception of Egyptian bowls), suggests that this area was used for storage and domestic activities.

South of the Sponge Divers’ House the structural remains are more plentiful, and at least three rooms here are strung out in a stepped-out pattern along the island’s spine. A stone oven with a ceramic cover and a stone bin were found inside one domestic structure (S107). Another structure (S119), where traces of two furnaces and bronze scraps were excavated, was probably a bronze casting workshop.

Walls were made of flat, undressed field stones brought from the mainland and laid in rough courses. Some walls were coated on the interiors with white or green plaster. Their superstructures may have been constructed of mudbrick or wattle and daub, but evidence for this is lacking, nor is there evidence for windows or doors. The natural bedrock surface of the island’s ridge, later supplanted by layers of trampled sand, provided the only flooring. Paving stones were used for an exterior court. All spacial units were extremely small, which presumably reflects the cramped size of the island.

Apart from animal/bird bones and shells, the principal finds from LBA strata were potsherds, with considerably fewer artifacts in stone, ceramic, faience and metal. Most of the imported pottery came from Cyprus, including both fine wares (Cypriot White Slip, White Shaved, Base Ring, Monochrome, Black Slip and Red Lustrous) and coarse wares (flat-bottom Plain White and Painted White Wheel-made jars and storage vessels). While Canaanite (Palestinian) jars formed the island’s largest class of storage vessels, Egyptian open bowls made up its largest single class of pottery. A small number of contemporary Minoan and Mycenaean sherds also occurred.

Evidence of the bronze workshop suggests that simple bronze tools were cast on the island for local exchange, and bartering of finished craft goods for food and water would have been crucial for the islanders’ operations. While the ethnicity of these people cannot be identified, they obviously had close ties with Cyprus. A motivation for short-term profit does not explain the existence of such a remote port, but it can only be understood in the wider framework of Late Bronze Age trade. Ship-borne Cypriot products have been discovered throughout much of the eastern Mediterranean, including Crete, the eastern Nile Delta and along the Levantine coast. Crete, which lies about 420km northwest of Matruh, was perhaps the final point west for eastern Mediterranean traders.

Given the strong north-westerly winds that prevail along this coast, Matruh represented the closest and safest landfall available to mariners leaving Crete to return to the Delta and other points in the eastern Mediterranean.

The local trading partners must have been the Berber Libyans that dominated the coastal plain and desert interior during the second half of the second millennium BC. A Libyan presence nearby is reflected in a handmade, coarse ware pottery, a few stone tools, and numerous ostrich eggshell fragments that were recovered from Late Bronze Age strata on the island, as well as five burials found by Oric Bates on the long ridge southeast of the modern town. The burials were in elliptical pits cut into the ridge’s soft bedrock. Two were intact, with human remains and grave goods including two small, well-made stone vessels, several handmade ceramic jars, a small stone "mortar" and a number of aquatic shells, three of which were thought to be of Nilotic origin. The ceramics, which were interpreted by Bates and Flinders Petrie to be of early, non-Egyptian origin, are currently awaiting laboratory tests for dating.

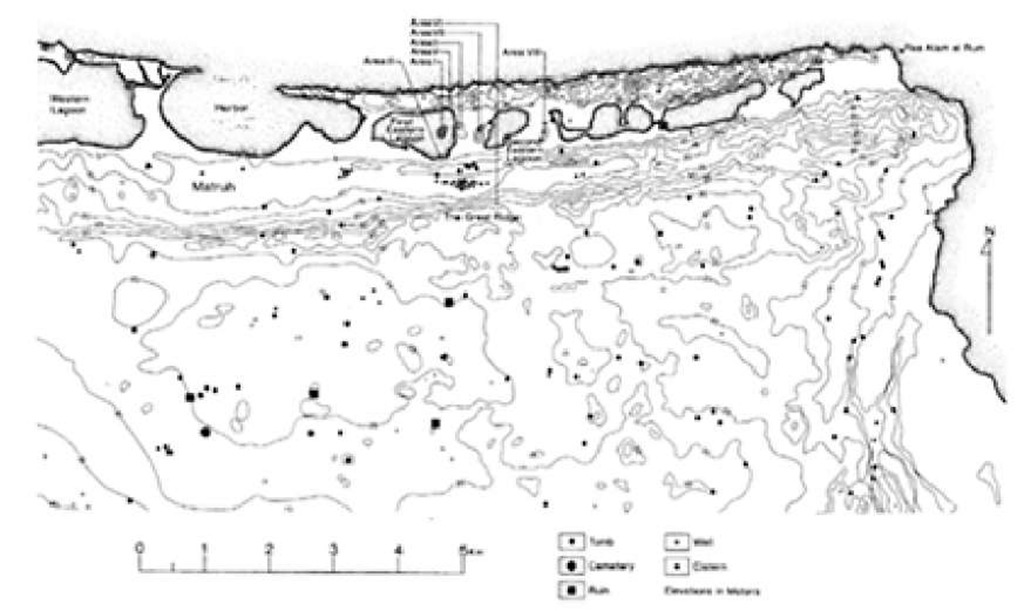

Figure 63 Central Marsa Matruh and the eastern lagoon system as far east as Ras Alam el-Rum

During the 18th Dynasty the Matruh area therefore seems to have provided eastern Mediterranean traders with fresh stocks of food and water supplied by the mainland Libyans, and perhaps locally manufactured bronze tools, in exchange for the standard trade goods routinely transported in ships. The island was probably shunned during the stormy winter months when the Libyans moved their flocks south.

While some form of settlement must have preceded Alexander’s visit, the town of Para-itonion is clearly linked with the Ptolemaic, Roman and Byzantine periods. Following the division of Alexander’s empire, it was administratively united with Ptolemaic Egypt. Although artifacts and wall remains have been found on Bates’s Island dating from the sixth century BC to the fourth/fifth centuries AD, the town’s Graeco- Roman development is better attested on the mainland. Bates observed urban remains spreading south of the southeast corner of Matruh’s first east lagoon. A set of rock-cut stairs associated with a rock-cut (burial?) chamber leading toward the lagoon’s edge may at one time have been associated with a dock. On the mainland west of Bates’s Island, the crest of the low outcropping of rock, still littered with Roman period sherds, has traces of some kind of ancient industrial facility (possibly associated with dyeing, given that murex shells turned up in some abundance on the island).

In 1904 the French observer Fourtau saw remains of a large, ancient rock-cut quay or pier at the southeast corner of the deep lagoon west of Matruh’s harbor, with a series of stone jetties projecting into the water. The quay’s extension was marked by stone towers at both ends, while more than 2km of urban remains, including a large domestic villa, were said by Fourtau to be visible along the lagoon’s south shore. A decade later Bates noted the same kind of development along the southern and eastern shore areas of the west lagoon. Today all traces of Fourtau’s and Bates’s ancient town and the lagoon quay have been obliterated by military construction and other modern development.

Bates was also aware that an important sector of later Paraitonion occupied the coastal ridge west of the harbor, but, with the exception of a Roman villa excavated by the Egyptian Antiquities Organization, this area has yet to be investigated. Bates observed a defensive wall sealing off the western end of the ridge-top settlement, which he attributed to the sixth century AD (Justinianic period); parts of this are still visible today. Fourtau noted a ridge-top cemetery in the same general area. In the 1930s a well-preserved line of a Roman period(?) aqueduct was surveyed 12km west of town; it presumably supplied the ridge settlement with sweet water.

Bates was able to record ten cemeteries and eight tombs of mainly Roman-Byzantine date associated either with the "Great Ridge" south of the modern city or with the regions to its west and southwest (i.e. extramural). He also excavated three large rock-cut tombs a short distance inland from the modern harbor. Rock-cut tombs were later reported at Hakfet Abdel-Razek Krim southeast of Matruh. Marble portraits of three local Egypto-Libyan males found in the tombs are in the Alexandria Museum.

Few historical facts are known about Para-itonion following the deaths of Marc Antony and Cleopatra VII, who resided there briefly after their defeat at Actium in 32 BC. Vespasian occupied the town during the civil war (AD 69) that led to his elevation as emperor. Otherwise, prior to the Byzantine period, when the town assumed considerable regional importance as both the seat of the dux limitis Libyci and of a bishop, Paraitonion was chiefly remembered as a source for a greasy, soft white mineral coloring agent called paraetonium.

Maspero, Sir Gaston Camille Charles

Born in Paris of Italian parents, Gaston Maspero (1846-1916) studied Egyptology there and in 1869 became Professor of Egyptology at the Ecole des hautes etudes. He earned the first Ph.D. in Egyptology in France and joined the faculty of the prestigious College de France in 1874.

Maspero’s first visit to Egypt in 1880, as head of a mission that would found the French Institute of Archaeology, involved epigraphic work in Thebes in the Valley of the Kings, but soon, with Auguste Mariette’s death, he was appointed Director of the Bulak Museum and of the Egyptian Antiquities Service.

Maspero opened late Old Kingdom pyramids and copied and published the funerary texts carved inside them. He also cleared and restored the Luxor and Karnak temples, but his greatest contribution to scholarship was arranging and cataloguing the vast holdings of the new Cairo Museum, resulting in fifty volumes during his lifetime. Not only a gifted philologist but also a brilliant historian, Maspero holds the publication record in Egyptology, with some 1,200 items on his bibliography. A master of the broad view of history, Maspero was one of the great intellects in the history of Egyptology. Perhaps his best known work was his multi-volume Histoire ancienne des peuples de l ‘orient classique (Ancient History of the Peoples of the Classical East) (1895-9).

Maspero also effectively reorganized Egypt’s Antiquities Service along lines which continue to this day, dividing the country into five inspectorates. Permissions to excavate were granted by a committee on his recommendation, and he did not exclude Egyptians from this, even in the face of criticism. Foreign institutions found him congenial in providing facilities and fair divisions of finds. He hired Howard Carter as Chief Inspector of Upper Egypt and was very supportive during Carter’s early career. Maspero was knighted by England in 1909, partly for his generous support of the Egypt Exploration Fund, founded in London in 1882, and he held many honorary degrees and memberships. He retired to France in 1914 at the end of his second long term of service in Egypt, and died suddenly in 1916, not long after his second son, a papyrologist, was lost in battle in the First World War.

Mazghuna

Mazghuna is the site of two destroyed pyramids of the late Middle Kingdom, on the west bank of the Nile circa 35km south of Cairo and 4km south of the cemetery of Dahshur (29°46′ N, 31°13′ E). The remains of these pyramids were excavated in 1910-11 by E.Mackay, who assigned them to Amenemhat IV (southern pyramid) and his sister/wife and successor, Neferusobek (Sobekneferu) (northern pyramid), the last two rulers of the 12th Dynasty. There is no textual evidence supporting these identifications and for archaeological reasons several scholars have suggested a 13 th Dynasty date, which seems more likely.

The southern pyramid measures circa 52.5m (100 cubits) at the base line and is slightly smaller than its northern neighbor. The superstructure, which was surrounded by a sinuous mudbrick enclosure wall, consists of a mudbrick core with a limestone casing. However, little more than the foundation trench of the casing and one or two layers of the mudbrick core are preserved.

The plan and construction of the burial chamber, with a built-in quartzite sarcophagus and transverse antechamber, aligned in the center of the pyramid, closely resemble the internal arrangement of the pyramid of Amenemhat III at Hawara. The entrance to the interior apartments of Amenemhat IV’s pyramid is on the south side of the pyramid, where a staircase with sliding ramps on either side leads down to a small chamber. In the east wall of this chamber a small doorway opens into a corridor, which leads north to the antechamber. To protect the burial from tomb robbers, two sliding portcullises of red granite were built into the entrance staircase.

No remains of a causeway were found. A small mudbrick structure consisting of an open court and a vaulted sanctuary, which are clearly the remains of the mortuary temple, was excavated in the center of the eastern enclosure.

Apparently the northern pyramid was already abandoned before it was finished. Both portcullises were found in an open position and there were no traces of a burial, which suggest that the pyramid was never used. Only a short section of a causeway-like ramp was found to the east of the complex, but there are no traces of an enclosure wall nor of the superstructure itself. The corridor system, which begins with a flight of steps on the east side of the pyramid, differs considerably from that in the southern pyramid at Mazghuna, but shows a close resemblance to the plan of the pyramid of an unknown king at South Saqqara. The T-shaped plan of the burial chamber and antechamber, which was first introduced in the pyramid of Amenemhat III at Hawara, was abandoned and replaced by a new design consisting of an oblong antechamber followed by a burial chamber with a built-in quartzite sarcophagus. A sliding block, which was intended to separate the two chambers, was found in an open position. This new system shows some resemblance to plans in contemporary private tombs and was probably first introduced in the pyramid of an unknown king at South Saqqara, where the so-called "queen’s tomb" adopted a similar plan.

Medamud

The site of Medamud (25°44′ N, 32°42′ E) is located about 5km northeast of Karnak, on the east bank of the Nile. Medamud was part of the Theban nome (Nome IV of Upper Egypt), and is mentioned between Thebes and Kus in the list of nomes and cities carved inside the temple of Ramesses II at Abydos. Its hieroglyphic name is "M3dw" (sometimes "M3tn" in demotic). The site was mainly dedicated to the falcon-headed or bull-shaped god Montu, and to a lesser extent, to his consort Rat-taui and son Harpora. Amen was also worshipped there, but at a later date.

The temple lies at the center of a partly destroyed circular mound and is roughly oriented along an east-west axis. Its ground plan includes the typical features of Graeco-Roman temples: a tribune (platform) overlooking a canal, a dromos that leads to a main gate, an open courtyard followed by a portico and a hypostyle hall, and a sanctuary. There was also space behind the sanctuary, which was apparently used as a courtyard for the living sacred bull.

No archaeological investigations took place at the site until Albert Daninos conducted a short survey there at the beginning of the twentieth century. The whole temple area was thoroughly excavated from 1925 to 1932 by the French Institute of Archaeology, Cairo (IFAO) in conjunction with the Louvre Museum, under the direction of Bisson de la Roque. Robichon and Varille, who did not publish a photographic record of their work, took over the fieldwork until 1939. Since then no excavations have been conducted there, but the gate of Tiberius and parts of an early Ptolemaic temple have been restored on paper by D.Valbelle and by C.Sambin and J.-F.Carlotti respectively.

Occupation of the site

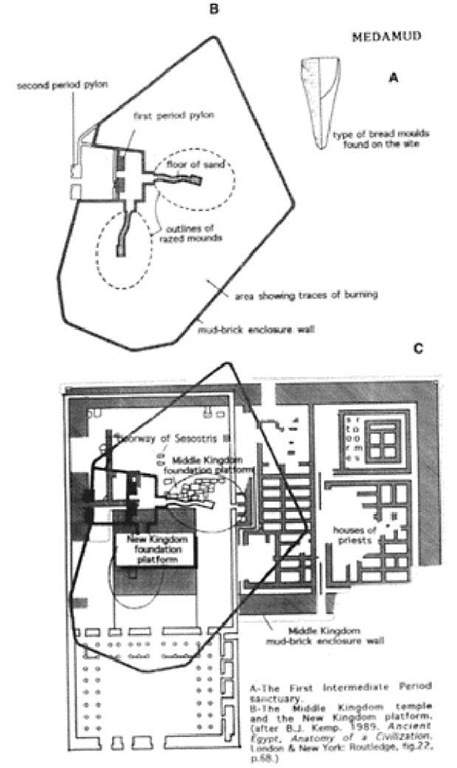

Little is known about the necropolis of Medamud or the pharaonic and Graeco-Roman period town, which may have extended toward the unexcavated southwestern part of the site. The oldest structure unearthed at Medamud is a First Intermediate Period mudbrick sanctuary. Inscriptions on the site begin mainly in the reign of Senusret III (12th Dynasty), and kings of the 13th Dynasty are well attested. In the New Kingdom Tuthmose III and his son Amenhotep II (18th Dynasty) were the most active builders there; however, only a red granite doorway of Amenhotep II is still visible today. The greater part of the present-day temple is of Graeco-Roman date, with some Coptic remains.

The earliest known construction at Medamud is a large, mudbrick polygonal enclosure wall, with a recessed entrance in its northeast section. Two mudbrick structures (later supplemented by two others) were identified as pylons; they led into a rectangular courtyard with vestibules in its western and southern ends. From the two vestibules were narrow, sinuous corridors, each of which ended in a small chamber. The floors of both corridors and chambers were covered with sand.

Unlike the rest of the area within the enclosure wall, two 20x15m oval-shaped areas around the two chambers showed no traces of fire. Robichon and Varille concluded that the site had been burned and that two egg-shaped zones were all that was left from two earlier mounds which had been razed after the fire, to make room for the Middle Kingdom temple. They associated the hillocks with the Osirian cult. Unfortunately, it is exceedingly difficult to know the purpose of this structure because of the lack of any written material from the earliest levels and the fact that Robichon and Varille’s interpretation was based solely on much later inscriptions. The ceramic evidence, including bread molds, seems to agree with a First Intermediate Period dating of the complex by the excavators; parallels were later found at the contemporary sites of Dendera and Balat in Dakhla Oasis.

The ground plan of the First Intermediate Period sanctuary appears to have been deliberately integrated into later constructions. The Middle and New Kingdom temples extended south and west, respectively, of the First Intermediate Period entrance, as did the original corridors and mounds.

Before reaching the First Intermediate Period structure, Varille and Robichon found the remains of a mudbrick temple. It was oriented along a north-south axis, with its northern half located under the eastern part of the later Graeco-Roman temple, and its southern half extending in the area east of the Graeco-Roman sacred lake. The better preserved southern half of the complex apparently contained priests’ houses and storerooms, mentioned on the Cairo Museum funerary stela from Abydos (CGC 20555) as "the granaries of the temple of Montu in Medamud." The only probable stone architectural feature of the Middle Kingdom found in situ by Bisson was an inscribed red granite doorway located near the center of the rear part of the Graeco-Roman temple, from the reign of Senusret III. It was oriented along the same axis as the structure unearthed by Robichon and Varille, and possibly the six foundation deposits found under this temple can also be attributed to Senusret III.

Most of the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period architectural features at Medamud were discovered as reused material. More than 150 inscribed blocks were removed from the foundations of the later New Kingdom temple, which lies beneath the front part of the Graeco-Roman temple. Many of them were originally from limestone doorways, such as the heb-sed (jubilee) portals built by Senusret III and Sobekhotep II (13th Dynasty), now in the Cairo Museum. Another set of limestone blocks that formed a gate, originally leading to the storehouse of divine offerings of Montu, was begun by Senusret III and finished by Sobekemsaf, a ruler of the late Second Intermediate Period. It is now set up in the open-air museum at the temple of Karnak along with another pair of limestone door-posts and a lintel. These doorways were fitted in a mudbrick structure, probably the Middle Kingdom enclosure wall.

Another 13th Dynasty king, Sobekhotep III, usurped many lintels and door jambs. He had his cartouche carved on columns, which seem to have been the only standing sandstone structure at that time at Medamud. A red granite stand, also unearthed from the New Kingdom foundation platform, contains the names of the otherwise obscure 13th Dynasty kings, Wugaf and Amenemhat-Kay. Late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period kings give the impression that they merely reproduced or completed monuments of their illustrious predecessor, Senusret III.

Limestone architraves from the reign of Senusret III, along with other reused blocks from the New Kingdom and Late period, were excavated from the thresholds of the Graeco-Roman temple. This demonstrates that part of the Middle Kingdom temple was still standing during the reigns of the first Ptolemies. Lack of more architectural evidence at Medamud from the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period can be explained by the destruction of limestone blocks to produce lime.

Figure 64 Medamud: A, types of bread molds found at the site; B, plan of the First Intermediate Period temple; C, plan of the Middle Kingdom temple

A number of Middle Kingdom statues are known from Medamud. The earliest written record from the site comes from a seated diorite statue of Senusret II, which was recovered in front of the temple portico. A series of diorite statues of Senusret III were unearthed throughout the temple. With great realism they portray the king at different periods of his life.

New Kingdom

None of the Middle Kingdom and First Intermediate Period blocks removed from the foundations of the New Kingdom temple showed any traces of hacking where the name of Montu was inscribed. This supports the theory that the temple was rebuilt before Akhenaten’s time. Most likely, Tuthmose III was the founder of the New Kingdom temple. His name was written on a calcite tablet that was part of a foundation deposit discovered next to the New Kingdom foundation platform, and Minemose, the Overseer of Works, mentions on a statue found in the rear of the Graeco-Roman temple that he attended a grounding ceremony inside the temple of Montu in Medamud under Tuthmose III.

The New Kingdom temple was oriented along an east-west axis. This change is not only demonstrated by the orientation of the New Kingdom foundation platform, but also by the red granite gate erected by Amenhotep II and the rooms in the front part of the Graeco-Roman temple, which comply with the New Kingdom east-west axis. Unfortunately, the plan of the New Kingdom temple cannot be determined. All that is known is that a large mudbrick enclosure wall was erected, and, according to the inscription on the statue of Maanakhtef found at Medamud, a festival hall existed during Amenhotep II’s reign. Tuthmose IV probably added a building of his own.

Earlier scholars believed that Akhenaten erected buildings at Medamud, but this is very unlikely. The numerous talatat blocks discovered at the site originally came from Akhenaten’s temples at East Karnak, as their small size enabled them to be easily transported.

Possibly some of the scanty Ramesside remains at Medamud were likewise brought from another site. William Murnane observed that an unpublished reused block of Seti I’s, which was found in the gate of Tiberius at Medamud, refers to a building called "excellent is [Seti] [in] the house of Amen westward of Thebes," the name given to his mortuary temple at Gurna on the west bank of the Nile.

Late period records for Medamud are scarce. According to an inscription in a chapel from the precinct of Mut at Karnak, Montuemhat of the 25th Dynasty restored the temple and erected a statue of Montu.

Two successive structures were built at Medamud during the Ptolemaic period. From the reigns of Ptolemy II Philadelphus to Ptolemy IV Philopator, buildings were set up in the southwestern part of the site. Ptolemy II Philadelphus raised a heb-sed gate in honor of Osiris, whose cult at Medamud and the Theban region grew significantly under the Ptolemaic kings. A foundation deposit with the name of Ptolemy III Euergetes came to light under a 27x16m temple extending in a north-south direction. The Theban uprising that occurred during the reign of Ptolemy IV may explain the unfinished state of his gate (now standing along with that of Ptolemy III in Lyons) and ultimately the destruction of the first temple.

From the reigns of Ptolemy V Epiphanes to Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos, the present-day east-west axial temple was erected. Ptolemy V and Ptolemy VI Philometor possibly built the sanctuary area, of which hardly anything is left. Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II constructed the portico, which was later inscribed by Ptolemy X Alexander and Ptolemy XII. Ptolemy XII also ordered the erection of the three kiosks to the west of the court (of Antoninus Pius). A sharp distinction between the two construction phases is shown by the reuse of the earlier Ptolemaic temple’s blocks in the foundations of the latter one, and by the clearcut distribution of cartouches in both temples.

Figure 65 Medamud: plan of the Graeco-Roman period temple

Textual evidence can sometimes throw light on otherwise obscure archaeological data. A commemoration stela (inv. 8668 of the 1935-6 Medamud site book, in the IFAO archives) found 2m from the gate of Tiberius mentions the construction of the mudbrick enclosure wall under the Roman emperor Augustus. The measurements of the wall given in the stela (176m long) match very closely those recorded at the site (172m). Contrary to widespread opinion, Tiberius probably did not build the gate, but merely decorated the monument that had been erected by his predecessor. The gate is named "the door of administering justice," a term which designates the open-air area where local disputes were dealt with. The four-pillared courtyard to the south of the three kiosks may have served a similar purpose under the last Ptolemaic kings. The damage seen on figures on the gate blocks probably occurred in Coptic times.

It is difficult to differentiate the actual construction phase of a building from when it was decorated. This is particularly true for the Graeco-Roman period, and the use of cartouches as a dating criterion can be misleading. However, it seems likely that the last temple of Medamud was near completion under the Ptolemies. Judging from the cartouches of Augustus and Vespasian on the thick north-south wall to the east of the three kiosks, the wall is of Roman date. But the kiosks, which are adorned with Ptolemy XII’s name, are of a later date than the wall, as they were clearly built leaning against the wall. Thus, this north-south wall was constructed earlier than Ptolemy XII’s reign, but it was decorated in the Roman period.

The Roman contribution may have been mainly of a decorative nature. Vespasian had a hymn to Amen-Re inscribed on part of the wall west of the court where the emperor Antoninus Pius later raised or decorated the double colonnade. The exterior enclosure stone wall of the Graeco-Roman temple was decorated by Trajan, and Domitian had its cornice carved. The famous scene of the bull, engraved on a stone projection on the exterior face of the south enclosure wall, shows the god delivering an oracle before the emperor (probably Trajan). A sacred lake, a well and a crypt were built during the Graeco-Roman period, as well as the dromos and tribune, which probably connected Medamud to the precinct of Montu at Karnak. Unfortunately, their exact date of construction is not known. The temple and town were apparently destroyed during the reign of Diocletian, who left his cartouche on a reused block fragment. In Coptic times, two churches were built in the temple area.

Montu, the local god

Middle Kingdom inscriptions refer to Montu as practically the sole god worshipped at Medamud. From the Boulaq Papyrus 18, a procession is described in which the statue of Montu was brought from Medamud and carried for two days to the royal palace in Upper Egypt, during the reign of Sobekhotep II. From the New Kingdom onward, the god also appears in the form of Montu-Re, or later as Amen-Re-Montu, when Montu was gradually superseded by Amen.

The inscriptions at Medamud emphasize Montu’s chief role as a warrior god. Senusret III set up a limestone doorway, named "Senusret, who drives the evil away from the Lord of Thebes who lives in Medamud." The temple was also described as a fortress, the so-called "house of fighting." In Graeco-Roman times, reference is often made to an "arena" in which the bull god contended with evil forces.

The quadripartite nature of Montu is another crucial feature of the god: "he is the one with four heads on a single neck." This quadripartite division of the god stresses his ability to control the universe through the domination of its four cardinal points, which materialized in the four cities that embraced and guarded Karnak: Armant, Tod, (North) Karnak and Medamud. Four pairs of Ptolemaic limestone statues of Montu and his consort Rat-taui were discovered in the rear section of the Graeco-Roman temple; each pair carried an inscription which made them the lords of these four cities.

Another important feature of the god described in the Medamud texts is his cosmogonic character. In the first Ptolemaic temple, the gate of Ptolemy IV was oriented toward the holy place of Djeme at Medinet Habu, where the Ogdoad (eight gods) went to rest after having given birth to Ptah and Atum in Memphis and Heliopolis, respectively. Medamud was then believed to be the last stop before Djeme, and Montu, whose statue was probably taken out of the temple on special occasions to face the sacred hill, was thereby associated with the creation myths of the universe.