Infections from Free-Living Amebae

Although amebae such as E. histolytica cannot survive and replicate outside of animal hosts, most amebae are free-living in soil or water. Amebae of the genera Naegleria, Acanthamoeba, Bal-amuthia, and Sappinia can cause acute meningitis, acute menin-goencephalitis, or chronic granulomatous meningoencephalitis [see Figures 15 and 16].91-93 Naegleria species, notably N. fowleri, cause acute meningoencephalitis in immunocompetent hosts; infection has been reported after trauma in warm freshwater in the southeastern United States. Progression of disease is typically rapid and inexorable, although effective therapy has been reported with amphotericin B, miconazole, and rifampin.

In addition to chronic granulomatous meningoencephalitis, Acanthamoeba species have been recognized as a cause of kerati-tis95 and, in a small number of HIV-infected patients, of disseminated disease with cutaneous manifestations.96 Acanthamoeba or ganisms have been isolated from water, airborne dust, hot tubs, and saline solutions used to clean contact lenses. Factors associated with the development of amebic keratitis include the lack of effective disinfection of contact lenses, a history of minor corneal trauma, and exposure to soil or standing water. The lesions, which are usually chronic and severely painful, consist of variable anterior uveitis, epithelial erosion, scleritis, and an infil-trative stromal keratitis that is often ring shaped. Lesions are refractory to the usual antimicrobial medications and must be distinguished from keratitis caused by herpes simplex virus [see 7:XXVIHerpesvirus Infections]. The diagnosis can be made by microscopic examination of Giemsa- or trichrome-stained corneal scrapings and by the use of indirect immunofluorescent antibody staining of corneal scrapings. The amebae can be cultured by inoculating corneal tissue into nonnutrient agar seeded with Escherichia coli. Acanthamebic keratitis has been treated with topical regimens using chlorhexidine (bis-biguanide) and propamidine or the polymeric equivalent polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB). PHMB was originally combined with propamidine but is now combined with hexamidine.95 This topical therapy is usually effective for patients presenting within 8 weeks, and cure can be achieved in 4 weeks of therapy.95

Trichomoniasis

Trichomonas vaginalis is a flagellated protozoan that causes an estimated three million vaginal infections a year.97 It is a venereal disease, with the highest incidence in women who have multiple sexual partners; thus, persons with Trichomonas infection should be screened for other sexually transmitted pathogens, such as Chlamydia, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and HIV. Trichomonas infection can be passed to neonates, and 2% to 17% of infected women transmit it to their female offspring during birth. It does not have a cyst form but, rather, only the trophozoite form, so that human-to-human transmission is the norm, although T. vaginalis can exist outside of the host for several hours if it is in a moist environment. Trichomonads appear to damage genital epithelium by direct contact, and this results in microulcerations and inflammation. Management of trichomonal infection is discussed in detail elsewhere [see 7:XXII Vaginitis and Sexually Transmitted Diseases].

Figure 14 A transmission electron micrograph shows developing forms of Encephalitozoon intestinalis inside a parasitophorous vacuole (red arrows) with mature spores (black arrows).

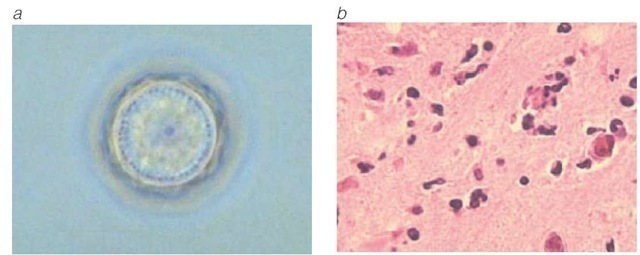

Figure 15 (a) Acanthamoeba polyphaga cyst. (b) A histopathologic slide shows A. polyphaga infection in a mouse brain. Similar histopathologic features are seen in Acanthamoeba meningoencephalitis, which generally occurs in immunocompromised persons.

Leishmaniasis

Leishmania organisms are protozoan hemoflagellates that are obligate intracellular parasites in humans. Leishmania species produce a wide spectrum of disease, ranging from generalized visceral involvement to diffuse or circumscribed cutaneous or mucocutaneous lesions. Four species complexes of Leishmania may infect humans: L. donovani, L. tropica, L. mexicana, and L. (subgenus Viannia) braziliensis. The resulting patterns of illness arise from the tissue tropism of the leishmanial species and the host’s immune response, principally the cell-mediated component of immunity.

Visceral leishmaniasis

Etiology and Epidemiology

The L. donovani species complex includes several species (e.g., L. infantum and L. chagasi). These species cause visceral leishma-niasis, or kala-azar, which is endemic in areas of India, China, Central and South America, East and West Africa, and the countries surrounding the Mediterranean. L. tropica can also cause a viscerotrophic disease involving bone marrow cells.98 Sandflies of the genus Phlebotomus are the insect vectors that spread L. donovani; the species vary in the different areas. In India, no ex-trahuman reservoirs are known, but in other regions, infection may involve several mammalian species, including dogs, foxes, and wild rodents.

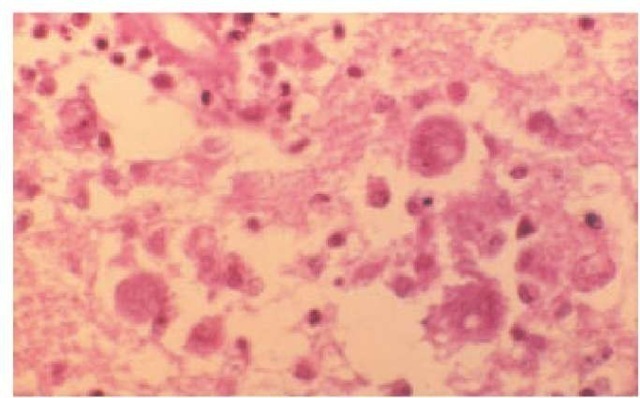

Figure 16 Naeglaria meningoencephalitis in a human brain, on hematoxylin-eosin stain.

Pathogenesis

The flagellated promastigotes of L. donovani are introduced by an insect bite. After entering macrophages of the reticuloen-dothelial system, these forms change into amastigotes, which multiply in phagocytic cells. Released amastigotes disseminate hematogenously and invade reticuloendothelial cells in the spleen, liver, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and skin. Prospective studies have demonstrated that the ratio of inapparent infection to disease ranges from greater than 6.5:1 in children younger than 5 years, the most susceptible group, to greater than 18:1 in older children and adults.99 Cell-mediated immunity controls Leishmania infection, and compromise of cell-mediated immunity, such as from young age or malnutrition, contributes to susceptibility.

Diagnosis

Clinical features Symptoms of visceral leishmaniasis usually have a gradual onset several months after infection and include weakness, dizziness, weight loss, diarrhea, and constipation. Fever, which almost always develops, may spike twice daily and is sometimes accompanied by chills and sweating. As the disease progresses, the liver and spleen enlarge, the latter often expanding into the iliac fossa. When bone marrow macrophages are parasitized, anemia and leukopenia ensue. The thrombocy-topenic patient may bleed from the gingivae, nose, or GI tract, and ecchymoses and petechiae may appear on the skin. Death can result from secondary bacterial infections, severe anemia, or uncontrolled bleeding. Latent infection can become manifest and progressive during immunosuppression, and visceral leish-maniasis can develop as an opportunistic infection in HIV-in-fected patients. Two thirds of patients with visceral leishmania-sis have typical infections, but leishmanial parasites may localize in unusual sites, including the larynx and throughout the GI tract, and hepatosplenomegaly may be absent.

Laboratory findings Anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytope-nia, hyperglobulinemia, and hypoalbuminemia suggest visceral leishmaniasis when they are observed in a patient with fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and a history of exposure in endemic areas. The differential diagnosis is wide, including hepatosplenic schistosomiasis, malarial hypersplenism, myeloproliferative diseases, typhoidal Salmonella infections, miliary tuberculosis, brucellosis, histoplasmosis, subacute bacterial endocarditis, and infectious mononucleosis. Definitive diagnosis of visceral leishma-niasis requires demonstration of the organism in host tissues cultured on a Novy-MacNeal-Nicolle (NNN) or other medium or detection of Leishman-Donovan bodies (amastigotes) in stained tissue samples. Alternatively, PCR can be performed using genus- or species-specific oligonucleotides. In most cases, the diagnosis can be established by examining bone marrow aspirates. Splenic aspirates have the highest yields but may be risky. Liver biopsy or aspiration of enlarged lymph nodes can also provide diagnostic material.

Treatment

Sodium stibogluconate (pentavalent antimony, 20 mg/kg daily I.M. or I.V. for 20 to 28 days) is the therapy of choice for treating most cases of leishmaniasis and is available as Pen-tostam through the CDC Drug Service (404-639-3670, days; 404639-2888, nights and weekends) [see Sidebar, Protozoan Infection Information on the Internet].10 Miltefosine has been shown to be effective in India for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis.100 The dose of miltefosine is 2.5 mg/kg/day, preferably in two divided doses or a single dose, orally for 28 days. When initial treatment of kala-azar with sodium stibogluconate fails, amphotericin B or pentamidine may be used.10 Kala-azar that is resistant to sodium stibogluconate may respond to liposomal amphotericin B.

Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

Etiology and Epidemiology

Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by three species of Leishmania that belong to the L. tropica complex: L. tropica is present in the Middle East and the Mediterranean littoral; L. major is found in the Middle East, Arabia, the former Soviet Union, India, and sub-Saharan Africa; and L. aethiopica is found principally in Ethiopia and Kenya. Phlebotomus sandflies are the principal vectors, although direct contact with an ill person may, in rare cases, result in infection. Infections that are caused by Leish-mania can be acquired by travelers, as well as by military and other personnel residing in endemic areas. Military personnel in the Middle East have acquired cutaneous leishmaniasis with L. major and viscerotropic infections with L. tropica.

New World cutaneous leishmaniasis arises from infection with parasites belonging to the L. mexicana group or the L. braziliensis (Viannia subgenus) group. The Viannia subgenus is distinguished from the Leishmania subgenus by the differences in development in the sandfly gut. The patterns of illness vary with the nature of the infecting leishmanial organisms, which are found in different regions of North, Central, and South America [see Table 3]. In areas of Central and South America, infection with organisms of the L. mexicana group produces cutaneous leishma-niasis. A few autochthonous cases have been found in Texas. Infections with strains of L. viannia, which are endemic in various areas of South America, cause cutaneous leishmaniasis and, in a small percentage of those infected, result in the later development of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Such mucocutaneous disease (espundia) involves the nasal or oropharyngeal mucosa, or both,and may prove fatal. All of these New World leishmanial parasites are transmitted principally by sandfly vectors, although direct human contact may also bring about infection. Various mammals are naturally infected reservoirs of the organisms.

Pathogenesis

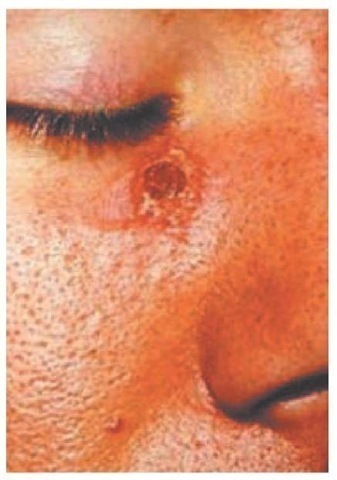

Both Old World and New World forms of leishmaniasis are initiated when the bite of an infected sandfly injects promasti-gotes into the human host. The organisms enter tissue macro-phages and capillary endothelial cells, become amastigotes, and multiply. A granulomatous inflammatory response develops at the bite site. With local ischemia, the lesion ulcerates [see Figure 17]; a bacterial infection of the necrotic area may extend the ul-ceration. Resolution of clinical infection is associated with CD4+ T helper type 1 cells that secrete interferon gamma in response to Leishmania. Progression of disease appears to be associated with an immune response dominated by interleukin-10, a cy-tokine that suppresses other cytokine responses.

Diagnosis

Clinical features In Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis, after an incubation period of weeks to months, a papule develops at the inoculation site. This area may resolve spontaneously. More frequently, it ulcerates and a shallow circular lesion appears that is several centimeters in diameter and has a raised margin. Bacterial superinfection may lead to regional lym-phadenopathy. The lesions are often solitary, but multiple bites can produce several concurrent lesions. Healing of the lesions is slow, sometimes requiring more than a year.

|

Protozoan Infection Information on the Internet |

|

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases |

|

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd Information on parasitic diseases, including DPDx, an online interactive diagnostic service (http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx) |

|

CDC Drug Service http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/srp/drugs/drug-service.html Information on special immunobiologic agents and drugs distributed through the CDC Drug Service, Scientific Resources Program, and the Division of Quarantine of the National Center for Infectious Diseases |

|

Emerging Infectious Diseases http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid The online edition of the peer-reviewed journal published by the CDC’s National Center for Infectious Diseases (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod) World Health Organization |

|

Division of Control of Tropical Diseases http://www.who.int/ctd Scientific publications and other information from the WHO’s lead program for the control of tropical diseases Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical |

|

Diseases http://www.who.int/tdr |

|

Disease information, image library, publications, research guidelines, grant applications, and other information from a scientific collaboration of the United Nations Development Program, UNICEF, the World Bank, and the WHO |

|

Karolinska Institutet |

|

University Library: Diseases and Disorders—links pertaining to parasitic diseases http://www.mic.ki.se/Diseases/C03.html |

Table 3 New World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis97

|

Parasite |

Disease in Humans |

Geographic Areas |

|

Leishmania viannia group L. viannia braziliensis |

Usually a single or few lesions but frequently very large, persistent, and disfiguring; later nasopharyngeal involvement (espun-dia) in a small percentage |

Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Venezuela, Paraguay, Colombia, northern Argentina, Belize, Guatemala |

|

L. viannia colombiensis |

Usually a single lesion |

Colombia, Panama |

|

L. viannia guyanensis |

Pian bois (bush yaws); multiple skin lesions, frequently with metastatic spread along lymphatics |

Guyana, Suriname, Belize, northern Brazil |

|

L. viannia panamensis |

Usually a single lesion but occasional spread via lymphatics; nasopharyngeal involvement rare |

Panama, Costa Rica, Colombia |

|

L. viannia peruviana |

Uta; a single or few self-healing skin lesions; no nasopharyngeal involvement |

Western slopes of the Peruvian Andes, the Argentinian highlands |

|

L. mexicana group L. mexicana mexicana |

Frequent involvement of ear pinna (chiclero’s ear, bay sore); a single or few skin lesions; no nasopharyngeal lesions; diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis rare |

Mexico, Central America, Texas |

|

L. mexicana amazonensis |

Rare human infection; a single or few skin lesions; diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis |

Amazon basin and neighboring areas, Brazil |

|

L. mexicana pifanoi |

Simple and diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis |

Venezuela |

|

L. mexicana venezuelensis |

Simple cutaneous leishmaniasis |

Venezuelan Andes |

|

L. mexicana species |

Simple and diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis |

Dominican Republic |

L. mexicana infections produce a single lesion or a few lesions on exposed surfaces of the body such as the face and ear.102 The ulcer usually heals spontaneously over 6 months. An ulcer involving the ear, however, may cause extensive destruction of the pinna. L. viannia infection is associated with lesions on the skin or mucous membranes, which may be multiple and may become very large, especially when bacterial superinfection develops. Cutaneous lesions caused by L. braziliensis are much less likely to heal spontaneously than those caused by L. mexicana.102 L. viannia braziliensis species can invade regional lymph nodes and cause progressive ulcerations along the lymphatics or extend locally and involve mucous membranes. Often, the infection metastasizes to the nasal or oral mucosa after an intervening period of months to years. Metastatic lesions can erode the nasal septum or the hard palate or soft palate. Some patients die of malnutrition or bacterial infection.

Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis occurs in parts of Ethiopia, Venezuela, Brazil, and the Dominican Republic. The initial nodule does not ulcerate; instead, multiple nodules evolve on the body. Leishmanial organisms abound in the lesions. Patients with this form of leishmaniasis have a deficiency of cell-mediated immunity, which is similar to the defective immunity that occurs in patients with lepromatous leprosy.

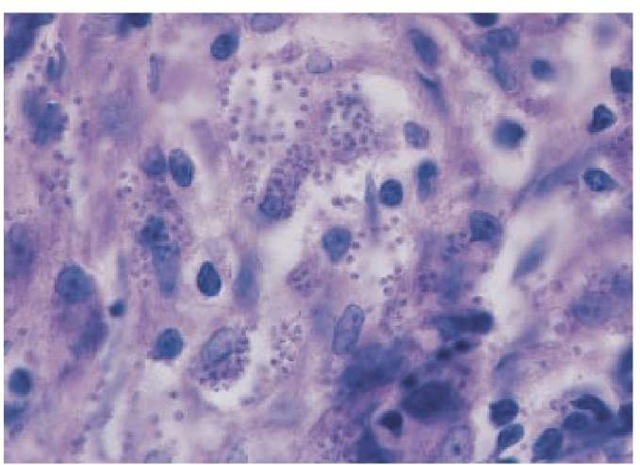

Laboratory findings Definitive diagnosis is made by demonstrating amastigotes on stained smears [see Figure 18] of a biopsy or of scrapings from the border of an ulcer. Alternatively, the diagnosis can be made by culturing amastigotes on NNN medium inoculated with lesion material. Use of PCR targeting parasite kine-toplast DNA has allowed detection of organisms that might be missed on histologic section or culturing. Moreover, this technique serves as a rapid method for speciating L. mexicana and L. viannia. In contrast to L. tropica and L. mexicana amastigotes, which can be readily cultured and are abundant in lesions, L. viannia amastigotes are difficult to culture and are sparse in lesions, especially those of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Organisms of these species cannot be distinguished morphologically, and specialized immunologic, enzymatic, or nucleic acid studies may be needed for definitive speciation. Except in diffuse cutaneous leishmania-sis, the leishmanin skin test is usually positive.

Treatment

Although the pentavalent antimonial compounds, sodium stibogluconate (20 mg/kg/day I.V. or I.M. of pentavalent anti-monial for 20 days) and meglumine antimoniate, are the general treatments of choice for both Old World and New World cutaneous leishmaniasis,10 optimal therapeutic regimens with these or alternative agents have not been rigorously defined. Individual species and geographic strains of Leishmania respond differently to treatment and have different capacities to cause mucosal disease or to heal spontaneously.

Figure 17 An ulcerative lesion of L. (Viannia) braziliensis acquired in the jungles of Belize.

Furthermore, it is difficult to distinguish infective species solely on clinical grounds. Therefore, progress in developing rational plans for appropriate treatment has been impeded. Advice on treatment of leishmaniasis is available from the CDC’s Division of Parasitic Diseases [see Sidebar, Protozoan Infection Information on the Internet]. Leishmania organisms have ergosterol in their membrane and are sensitive to amphotericin-containing preparations and azole 14-demethy-lase inhibitors. Amphotericin B and lipid preparations of am-photericin have been shown to be effective for mucosal leishma-niasis resistant to antimonial compounds. For Old World cutaneous disease with L. major, treatment with fluconazole (200 mg daily for 6 weeks) has been shown to be effective.103 Pentamidine and topical paromomycin have been used as alternatives for treatment of cutaneous disease.

Trypanosomiasis

American trypanosomiasis (ChAgas Disease)

Infection with the protozoan hemoflagellate Trypanosoma cruzi produces American trypanosomiasis, or Chagas disease, which has acute and chronic forms.104

Etiology and Epidemiology

Two forms of T. cruzi infect mammals: trypanosomes, which are carried in the blood, and amastigotes, which are found in infected cells. The parasite is transmitted by several genera of re-duviid or triatomid bugs, commonly called assassin bugs because they prey on other insects or called kissing bugs because of their predilection for biting the face [see Figure 19]. Nonhuman reservoirs include cats, dogs, rats and other rodents, raccoons, opossums, and armadillos. The local pattern of transmission of T. cruzi infections depends on the species of reduviid bug, the sylvatic and domestic mammalian reservoirs, and housing conditions. Infected animals living around dwellings, usually in rural areas, are likely to transmit the organism to reduviid bugs. These infected bugs inhabit niches in walls and ceilings of poorly constructed houses. At night, they come out and feed on the blood of sleeping humans by biting exposed skin areas such as the face. During their meal, the insects excrete feces containing infective-stage metacyclic trypanosomes, which enter the host through the bite wound, cutaneous abrasions, or mucous membranes of the conjunctiva or lips.

Figure 18 Amastigotes are demonstrated on Giemsa-stained biopsy tissue from an ulcer in a patient with Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Although reduviid vectors are present in the United States and infected mammals have been found in several states, the opportunity for transmission of infections seems limited. Only five autochthonous cases of Chagas disease have been reported in the United States.105 In rural areas of Central and South America, human infections are common where conditions favor access of infected bugs to persons.104 In addition, infections may be transmitted by blood transfusions, across the placenta, to laboratory workers, and, in rare instances, by ingestion of foodstuffs contaminated with the excreta of infected reduviid bugs.