An icon for a propaganda campaign in the United States during World War II, promulgated by the War Manpower Commission and the Office of War Information. The campaign centered on a call for women to give up the homemaker ideal and to take up occupations that supported the war effort or fill jobs that were left vacant when the men went to war. As large numbers of American males were drafted for service in World War II, Rosie became immortalized in songs, movies, posters, and advertisements. The messages were highly patriotic and viewed women as "production soldiers."

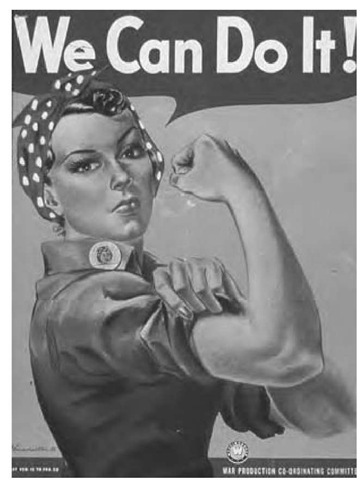

Many depictions of Rosie could be found during the war. The most famous rendition of Rosie was found on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post in 1943. In this familiar picture by Norman Rockwell, Rosie, shown eating a sandwich, is clad in coveralls, wearing headgear and goggles, and is supporting a large riveting machine on her legs, positioned just below her massive arms. In the background of this picture is an American flag, over Rosie’s head is a halo, and beneath her work shoes is a copy of Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Rockwell modeled his version of Rosie after Michelangelo’s Isaiah, significantly modifying his real model’s small frame. In another familiar poster often considered to represent Rosie, a young woman adorned in bandana and work shirt is seen rolling up her sleeve, flexing her bicep, and exclaiming, "We Can Do It."

The messages of this propaganda campaign were that women, especially married women who were previously relegated to working at home, should enter male-dominated occupations related to the war effort such as aircraft parts manufacturing, shipbuilding, ammunitions production, and mining. Women were also asked to enter nondefense-related manufacturing occupations in industry and agriculture.

Work in the defense industry normally required long hours, often entailed grueling physical exertion, and was frequently hazardous. Airplane factories were very loud and often caused hearing problems for the workers. Riveting vibrations were rumored to cause breast cancer and other physical maladies in workers; during this period, gynecological problems came to be known as "riveter’s ovaries." Some jobs were particularly dangerous, such as those in the munitions industry. Female munitions workers, dubbed "gunpowder girls," worked with the threat of explosions. Those who worked around machines—a large majority of defense employees—were at constant risk of death or dismemberment. In addition, the work was often monotonous and highly repetitive, causing high levels of boredom that was often relieved through singing. This new image of femininity challenged earlier gender conceptions. Men, who were unhappy to see women do well in occupations that were previously only open to males, often subjected women to harassment and other forms of discrimination.

We Can Do It poster, featuring Rosie the Riveter.

In spite of the occupations’ drawbacks, many women enjoyed the responsibilities of the new jobs and the newfound status of wage earner. The fact that they were able to succeed in these roles opened the door to a greater number of females in traditional male occupations. Although government and industry prompted Rosie to return to the home after the war and many were reluctantly replaced by returning males, the number of women who stayed in the workplace was higher than before the war.