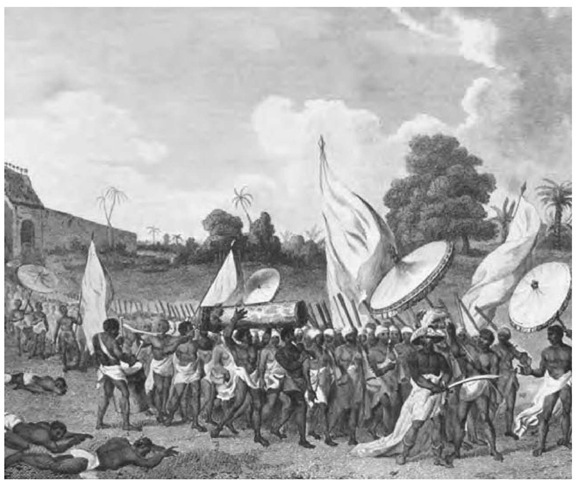

Female warriors of the Kingdom of Dahomey in West Africa. Enemies of Dahomey described its women warriors as frenzied cannibals, Europeans called them Amazons, and the people of Dahomey knew them as ahosi, or wives of the king, or mino, "our mothers." Initially these women of the palace served as the king’s guard. They fought for the kingdom as early as the beginning of the eighteenth century and, under the rule of Gezo (1818-1858), they became full-fledged warriors. By the mid-nineteenth century, their numbers averaged from 4,000 to 5,000, although some estimates went higher (Law 1993, 251). Gezo’s reign was characterized by constant warfare and slave trading, and his fear of a coup d’etat made him rely on women as his personal and political protectors.

The women warriors of Dahomey were exalted in Fon (Dahomey’s dominant ethnic group) society. Fon society allowed for this development because, although it was certainly male dominated, there were some arenas that allowed women a surprising amount of power. In all aspects of the national government and military, there were parallel positions for men and women, such as the king to the queen mother.

Both Fon and non-Fon women served in the military. In Dahomey, fathers brought their daughters to the palace, and only the tallest and strongest were selected. The bulk of the ranks entered Dahomey’s military either as slaves or prisoners of war. These women were not ethnically Fon, but their status as foreigners in the palace and lack of kin in the area facilitated their complete allegiance to the king, making them well-suited for their positions. All the Amazons lived in the king’s palace where men could not reside.

Visitors to the kingdom, especially Victorian Europeans, found the arrangement of the palace and the status of its female guards fascinating, and they recorded their impressions of the king and the women of the palace. Europeans were intrigued by the celibacy that most of these women practiced. As ahosi, they were permitted to have sex with no one but the king (although very few actually did), and adultery carried the death penalty. The threat of capital punishment did not deter all lovers, and when discovered, both the woman and her paramour would be executed. Contrary to popular mythology, there is evidence of neither clitoredectomy nor cannibalism, and reports of widespread lesbianism were created by the imaginations of European visitors to the kingdom. The women were supposed to channel the energy of their libidos into energy on the battlefield.

By all accounts, the female warriors were fierce no matter who the adversary or with what they fought. Firearms replaced less efficient bows and poisoned arrows. The women were usually outfitted with muskets that they fired from their shoulders. They also carried rope to tie up prisoners, along with gunpowder, cartridges, and short swords. Some carried razors from 18 inches to 3 feet in length that snapped into covers; they used these to take body parts as trophies.

The Amazons fought to subdue the enemy, to take prisoners, and to protect the king. Initially, the king was surrounded by his royal female guard in the front and at the center of the army, and the women and king were buttressed by male soldiers. After King Agaja was injured, however, the kings continued to go on campaigns, but they stayed to the rear of the action, still surrounded by Amazons. These women were the elite of the elite. Other women warriors and their male counterparts wended their way silently through forests and high grasses to participate in the surprise attacks favored by Dahomey. Women warriors did not fight in units with men but had their own corresponding units and fought in the same battles; women’s units were commanded by women.

An engraving entitled Armed Women with the King at Their Head by Francis Chesham (1749—1806).

The dress of the Amazons did not easily distinguish them as women. Even in the palace and on military parade, they wore sleeveless, kilt-length tunics and shorts. In the palace, their uniforms were blue and white striped, and on campaign they wore brown. Each unit sported its own hairstyle. Contrary to popular belief, they left both breasts intact.

The women underwent intense physical training accompanied by education in their traditions, use of weapons, gymnastics, and all they needed to know to be outstanding warriors. Because of their training and positions in Dahomey, the ahosi had a much greater degree of autonomy than other women in the kingdom. The Amazons disdained "women’s work." They spent some of their leisure time drinking alcohol, dancing, and singing songs proclaiming that the men would stay in Dahomey planting crops while they would defeat and eviscerate their prisoners.

In 1851, Dahomey attacked the town of Abekuta after many counselors, including women of the palace, had advised the king against it. It ended in a crushing defeat for Dahomey, and nearly 2,000 women warriors, half their original number, perished. Years of warfare had weakened the kingdom and as French troops encroached, the Dahomey fought them off to the best of its ability. Considering the outdated weapons with which they fought, Daho-mian forces inflicted considerable casualties but were unable to save the kingdom.

In fighting both Africans and Europeans, the Amazons raised the hackles of their adversaries because they were women. Legend says that when the men of Abekuta discovered that they fought women and that some of their ranks had been killed by the women warriors, their shame drove them to fight twice as hard to defeat the invaders. The French recounted stories that the Amazons drank themselves into drunken frenzies before battles. Some European men said that these women were hideously ugly, and others reported that they were beautiful. Commander Terrillon called them harpies, while many of his men greatly enjoyed watching defeated Amazons bathe in a nearby pond, insisting that they were some of the loveliest women in the world (Markouis 1974, 253; Mercer 1964, 177).

The arrival of the French ended the once-strong kingdom of Dahomey, and the corps of women warriors disbanded. Some would marry (although some suffered from low fertility rates); many others refused to wed, declaring no desire to ever be subordinate to men. These women— who gained such respect, who were feared and revered—could not reconcile themselves to returning to a life in which, for reasons of gender, status, origin, or all of these, they could never again be part of society’s elite.