The impact of the Russo-Chechen wars on women. Since 1994, Chechnya has experienced two destructive wars. Indeed, the wars have triggered a transformation of gender roles. If female Chechen suicide bombers, who made their first appearance in 2000, embodied a new involvement of women in the war and terror, they only represent a small fraction of the Chechen female population. They, however, do reflect the societal changes brought about by war.

In 1991, the small North Caucasian Republic of Chechnya unilaterally declared its independence from the nascent Russian Federation. After two and a half years of political and economic pressures and negotiation, President Boris Yeltsin’s Russian administration decided to launch a military campaign. Lasting from December 1994 to August 1996, the war, according to various estimates, caused between 50,000 and 100,000 deaths (Cherkasov 2004, 7-8). In the aftermath of the conflict, a problematic political situation prevailed and new tensions appeared between the two former belligerents. At the same time, the persisting tensions significantly strengthened the Chechen’s opposition to Aslan Maskhadov, the newly elected Chechen president. An open conflict arose between the moderate Chechen president and the warlords who converted to radical Islam. By 1997, Chechnya was plagued by anarchical lawlessness.

On October 1, 1999, the Russian armed forces launched a second campaign in Chechnya as a result of two events. In August 1999, the radical warlord Shamil Basayev led an invasion of neighboring Dagestan, a constituent republic of the Russian Federation, with the aim of creating an independent Islamic north Caucasian state. Then in September, the bombing of three apartment buildings killed 300 people in Moscow and southern Russia. The Russian government blamed the attacks on Chechnya and argued that Chechen terrorism justified Russian military action. The military operations quickly turned into a tremendously destructive war. In 2003, after a referendum managed by the Russians, the Chechen Republic adopted a new constitution and organized a contested election that led to the nomination of a pro-Russian Chechen president. Russia subsequently claimed that the situation was improving, but, by early 2005, it remains dramatically unchanged.

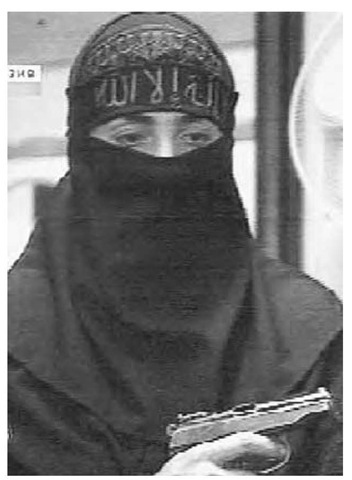

A woman, one of fifty armed Chechens who seized a crowded Moscow theater in October 2002, poses with a pistol somewhere inside the theater in this image from a Russian television station. Some of the women claimed to be widows of ethnic Chechen insurgents.

From the start of the first war, the Chechen civilian population has endured harsh conditions and extreme violence on a daily basis (Tishkov, 2004). The first conflict produced many documented atrocities against civilians, but the second has proved to be even more violent. The Russian armed forces have introduced new tactics, called mop-up or cleansing operations (zachistka) during which widespread human rights abuses are committed. At the same time, the Chechen resistance radicalized and some rebel groups have developed new strategies based on terror.

Throughout the Russo-Chechen wars, violence has primarily targeted men who are suspected of being fighters or of having links with pro-separatist or Islamist groups. They have been subjected to arbitrary arrest and detention in the filtration camps. They have frequently been tortured, if not executed. The violence, however, has never spared women. Although Chechen women rarely complain or openly express their sufferings, they have been undergoing two main types of violence. War first brought symbolic violence. Chechen women have been living in extreme precariousness and an insecure environment since the beginning of warfare. Many of them have lost one or several relatives who were either killed or abducted. Extrajudicial killings, illegal reprisals, arbitrary arrests, disappearances, torture, and looting have been pervasive. A ruined Chechnya has become a no man’s land where total impunity dominates. Many women have also experienced physical violence. As in other wars, rape of women has been part of the war in Chechnya. These sexual crimes are certainly underreported but are presumed to widely occur, particularly during nighttime raids and mop-up operations. Rape is extremely shameful in the traditional Chechen Muslim context. A woman who experiences sexual assault brings dishonor on her family and could be repudiated and even killed in the name of family honor.

This insecure and extremely violent context has been a catalyst for social changes. Indeed, it has had strong effects on gender roles within the Chechen society. In Chechen society, women are assigned the roles of housekeeper and guardian of ancestral traditions. On one hand, men typically insist on the central role of women in society, yet on the other, the men always relegate them to a subordinate position. Under the Soviet regime, women were granted better access to education. Hence, many of them played new roles in education, medicine, and commerce. Since the 1957 return of the Chechens from the deportation inflicted on them by Stalin, however, identity tensions arose between traditional representations and social injunctions and the effective roles women were playing within the society. These tensions were heightened after Dzhokhar Dudayaev, the first prosep-aratist president of Chechnya, encouraged a return to tradition. Even though this political move proved to have little impact on the private sphere, it aroused new frustrations for women, who were excluded from all public and political affairs.

The first war, in such a context, represented a turning point. While men took up arms to fight the Russian army, women became wholly responsible for their families. They became deeply involved in small commercial activities, selling on local markets either their own products or the merchandise that they had bought in the neighboring Ingushetia. Women relied on their traditional image of harmlessness to go through checkpoints and to cross the frontiers. Such trips were indeed hazardous; although the women may commonly have aroused less suspicion than men, they had to deal with the hostile soldiers’ attitudes, the widespread practice of extortion at checkpoints, and the risk of being kidnapped and raped.

This image of harmlessness has also served other purposes. Since the first war, women have played the role of negotiators or intermediaries with the Russian soldiers. For instance, they have bought the release of their relatives from the filtration camps or obtained the corpse of a relative for a fee. Since 2003, they have protested in the streets against arrests and arbitrary disappearances and denounced the inertia of the local pro-Russian Chechen administration. It seems that these demonstrations have not been spontaneous but have been encouraged by either opponents to the Chechen pro-Russian government or human rights activists. Women may thus become a de facto political force and assume a traditional male social role. This evolution has, of course, taken place in other wars, but it appears to be particularly significant in the Chechen case.

Far from being passive actors, Chechen women took an active part in the war. Those who fight represent an insignificant minority. Much more common is their support of the fighters. They have provided fighters with information, materials, and arms, as well as food and medical care. Since the first suicide attack was carried out by a woman in June 2000, however, the perception of the role of women in the Russo-Chechen war deeply changed. This act symbolized two concomitant evolutions. Suicide terrorism marks the radicalization of some rebel groups and the importation of new tactics. These attacks have become more numerous than other types of terrorism, and women have committed more than 50 percent of them. Since 2000, about 42 women have become martyrs (Shahidki), although no exact figures exist.

Female suicide bombers, while having their own personal histories, show some common characteristics (Juzik 2003, 161-168; Reuter 2004, 19). Most were young, educated Chechen women coming from a middle-class or privileged social milieu. All were directly or indirectly affected by the wars and lost at least one relative. Finally, only a few have links with Islamist groups. Three of the Chechen female suicide bombers were arrested before committing attacks. Their testimonies have to be viewed cautiously because they have been distorted and instrumentalized by both parties to their own purposes.

The Russians have interpreted the onset of suicide attacks as a sign of an Al Qaeda presence in Chechnya and suspect the existence of "Shahidki battalions." For some experts, women who fall into the hands of extremists are blackmailed after having been kidnapped, drugged, and raped; according to this view, they have been indoctrinated and forced to become suicide bombers to avoid dishonor. The Chechens, on the other hand, offer another explanation; according to them, the involvement of women shows the commitment of the whole nation to fighting the Russian invaders. Women commit suicide bombing on their own because of despair or to avenge their killed or abducted relatives. This version gave birth to the black widows myth, a term referring to the female members of the commando that took hostage the audience in Moscow’s Dubrovka theatre in October 2002.

All these interpretations are ideologically biased. To understand fully the commitment of these women, a distinction should be made between individual motivations and collective strategies. A strong correlation can be seen between the Russian mop-up operations and the rise of female suicide attacks. Hence, extreme personal commitment could be explained in most cases by motives of revenge and despair (Reuters 2004, 4). In July 2001, Sveta Tsagaroeva killed the military commandant responsible for the death of her husband and brother. Vengeance could have led her to suicide terrorism. In some other cases, religion may have played a more decisive role. Khava Barayeva had strong connections to the Islamist milieu; she was the niece of Arbi Barayev, the radical Chechen warlord killed in 1999, and the sister of Movsar Barayev, head of the Moscow commando. Individual motivations evidently vary.

Suicide terrorism must also be considered in light of a larger strategy that some of the rebel groups adopt. Indeed, the organizational dimension of Chechen terrorism is revealed by the targets of the suicide-bombing operations, which were first directed against military and political objectives, well before hitting civilians, and the logistic required for large-scale hostage-takings (the Moscow theatre and the school in Beslan in September 2004). This moreover suggests that while the involved groups claim to belong to radical Islam, religion assumes an instrumental role in most cases. Chechen terrorist attacks are part of a local conflict. The Chechen field commanders who are behind these attacks, although indisputably influenced by the Jihadi mercenaries who came to Chechnya during the first war and after, have not extended their agenda to a more global struggle against Infidels. Even the most radical leaders, such as Shamil Basayaev or Movladi Udugov, who both rely on the Islamist symbols and rhetoric make the independence of

Chechnya and the retreat of the Russian armed forces from North Caucasus their sole objectives. Those facts strongly undermine the Russian thesis. Suicide bombings appear in this regard as a worrying sign of the radicalization of Chechen society (Larzilliere 2003, 162). Political violence and the strong social uncertainties provoked by the conflict make women more vulnerable or more desperate, so that they have become a new military and psychological arm in the hands of radical warlords.

Some songs and poems celebrate the female suicide bombers and praise them for their devotion to the nation. It seems, however, that suicide terrorism rouses indignation and revulsion within the Chechen society. Notwithstanding the incomprehension and the disgust they incite, female suicide bombers symbolize the social transformations engendered by war.