If a single moment can be marked as sounding the death knell of Western colonialism, then surely it was in 1917, as the United States declared war on Germany, when Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924, president from 1913 to 1921) announced that:

The nations should with one accord adopt the doctrine of President Monroe as the doctrine of the world: that no nation should seek to extend its polity over any other nation or people but that every people should be left free to determine its own polity, its own way of development, unhindered, unthreatened, unafraid, the little along with the great and powerful.

Woodrow Wilson. President Wilson (standing center) waves to a crowd in Saint Louis, Missouri, on September 6, 1919, during a speaking tour to promote the League of Nations.

Hence, as the United States had said in 1823 with the Monroe Doctrine that it would interpose itself between the newly freed countries of Latin America, now Washington was proposing guidelines for Europe, the Middle East, and perhaps beyond. Here was the call for ”national self-determination” (Wilson’s pet phrase) for peoples subjected to colonial rule, Western or otherwise, uttered with clear determination by the greatest power of the twentieth century. To be sure, the chaos of the interwar years made Wilson’s announcement appear illusory, and three decades stretched between those momentous words and the independence of India and Pakistan. Still, Wilson attempted to implement the promise of democratic national self-determination immediately, at Versailles, as the victors in World War I deliberated what to do with the peoples released from imperial control with the disintegration of the German, Ottoman, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian empires.

The League of Nations, the precursor organization to the United Nations, was born of his hope, as was the independence of a number of countries of Eastern Europe and the mandate system that prepared certain peoples of the Middle East and Africa for eventual self-government. If only Czechoslovakia emerged much as the American leader had hoped from these grand designs, a framework had nevertheless been established that would guide later American presidents as they worked to refashion international order in the aftermath of World War II and the Cold War. Washington would work, in a word, to create a politically plural world, one free of imperial domination and constituted instead by democratic states linked by multilateral institutions for the sake of preserving the common peace.

The genius of Wilson’s design for world order was that it put American traditions and interests together in a package attractive for many of the peoples of the world. The basis of international order, Wilson held, should be democratically constituted states created by self-determining peoples. These states should interact with one another in terms of an open, nondiscriminatory international economic system. Disputes among them should be settled by a system of multilateral institutions based on

WOODROW WILSON’S MESSAGE TO CONGRESS

In 1917, Woodrow Wilson urged the United States Congress to declare war on Germany. What follows is part of this speech.

”We are glad, now that we see the facts with no veil of false pretence about them, to fight thus for the ultimate peace of the world and for the liberation of its peoples, the German peoples included: for the rights of nations great and small and the privilege of men everywhere to choose their way of life and of obedience. The world must be made sage for democracy. Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty. We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion. We seek no indemnities for ourselves, no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make. We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind. We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and the freedom of nations can make them.” the premise of collective security (rather than on the standard appeal to balance of power). In short, here was a framework for domestic and international order based on American interests and principles that corresponded to the hopes of nationalists in many other lands as well. Its consequence would be ”a world safe for democracy,” an international order composed of mutually respecting states interacting with peaceful reciprocity, the best guarantee the United States could have that its national security as a democracy would be preserved. As a result, the term Wilsonianism was born, the only ism attached to the name of an American president so far as world affairs is concerned. In due course, Wilsonianism was to become synonymous with liberalism in world affairs, and as such it has been an active ingredient in American foreign policy ever since.

At the time and since, there were many who disparaged Wilsonianism. Some doubted that democratic government held much appeal for many of the peoples of the world. Others were skeptical that even if democracy were to flower in much of the world it would create [what later liberals came to call] a ”pacific union,” a ”zone of democratic peace” —notions that harkened back to the writings of the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) in the late eighteenth century that democratic regimes were different from those based on authoritarian rule in that they would be more pacific toward one another. And yet others resisted these liberal appeals as solvents of the authoritarian and imperial systems they vowed to maintain.

The interwar years seemed to prove the skeptics right. The rise of communism and fascism, compounded by the Great Depression, made any hopes of a perfectible future seem utopian indeed. Nevertheless, the framework proposed by Wilson returned to inspire President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945) as he called for the creation of the Bretton Woods Accords (1944), which presided over the greatest liberalization of trade and investment in world history; as he oversaw the opening of the United Nations (1945-1946), which sought a new basis for conflict resolution among states; and as he promoted the Atlantic Charter (in 1941) and the Declaration on Liberated Europe (in 1945), which foresaw national self-determination for peoples liberated from Axis domination in World War II, as well as implicitly (and in due course) eventual self-government for those under European colonial rule.

Wilsonianism rested on four essential legs: (1) a call for democratic governments worldwide; (2) an appeal for an open and integrated international economic system; (3) a proliferation of multilateral organizations; and (4) the active involvement of the United States in maintaining this framework for order understood to be working for its own national security. However, of the four legs it is surely the emphasis on national self-determination, understood as democratic state building, that is justifiably understood as its most basic ingredient, even if its reassurance to an American public that primary security interests were guaranteed made it palatable at home.

It was on the basis of this political thinking that during World War II Roosevelt called for the independence of the peoples under British and French colonial rule and that he called upon Soviet leader Joseph Stalin (1879-1953) to restore the independence of those people liberated from Nazi rule by the Red Army. Roosevelt died in April 1945, but his successor Harry Truman (1884-1972) carried forth with this policy, pushing for European decolonization, opposing Soviet expansionism, and presiding over the democratization of occupied Germany and Japan.

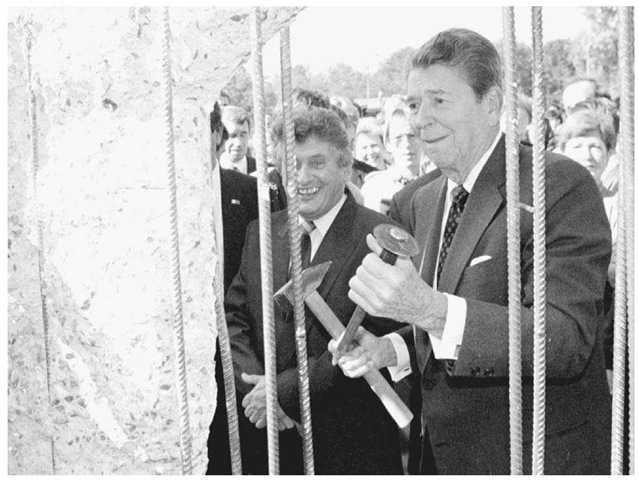

Reagan Helps Dismantle the Remnants of the Berlin Wall, September 12, 1990. The presidency of Ronald Reagan marked a high point in the resurgence of Wilsonianism. With the fall of Germany’s Berlin Wall in November 1989, Wilsonianism stood supreme as the premier blueprint for domestic and international order.

As the Cold War grew in intensity, Wilsonianism became something of a ”second track” in the conduct of American foreign policy. The ”first track” was called containment and aimed to prevent the spread of international communism. Yet at the same time a commitment to multilateralism, economic openness, and democratic government typified relations among Washington’s closest allies and its hopes for a wider network of contacts. When President John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) launched the Alliance for Progress with Latin America, or President Jimmy Carter (b. 1924) initiated his campaign for human rights, they were clearly within the Wilsonian tradition.

The presidency of Ronald Reagan (1911-2004) marked a highpoint in the resurgence of Wilsonianism not seen since the 1940s. Although Reagan eschewed the multilateralism typical of liberalism, he forcibly advanced the cause of democratic government worldwide, most notably within not only the Soviet empire but for the Soviet Union itself. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s (b. 1931) eventual embrace of this liberal creed was meant to reform, not to destroy, the leadership of the Communist Party and the legitimacy of the Soviet empire, but in short order these monolithic entities disintegrated, as did the Soviet Union itself. With the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, Wilsonianism stood supreme as the premier blueprint for domestic and international order.

The administrations of presidents George H. W. Bush (b. 1924) and Bill Clinton (b. 1946) continued in this liberal democratic internationalist tradition. The newly independent countries of central and east Europe were encouraged to democratize, and one way of aiding the process was to involve them in the multilateral organizations that had been born of World War II (including especially the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union). At the same time, democratic transitions in South Africa and South Korea could be saluted, marking as they did the spread of liberal values and institutions in still other parts of the world.

The presidency of George W. Bush (b. 1946) was at first distinguished by a distinct hostility toward democracy promotion abroad. The president, his first-term national security advisor Condoleezza Rice (b. 1954), and secretary of state Colin Powell (b. 1937), all declared their skepticism that ”state and nation building” should enjoy a high priority for American foreign policy. However, following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, a “born-again” version of Wilsonianism appeared, one that claimed that American security could only be preserved if the Arab Middle East (or a good portion of it) were democratized. The war on Iraq, launched in March 2003, was in this sense a democratic crusade designed to reform a foreign people in ways in keeping with American security interests.

In the minds of many, the question raised by the war on Iraq was whether Wilson’s old pledge to ”make the world safe for democracy” had perhaps taken a perverse turn so that now democracy was itself not safe for world order. The demands placed by the Bush administration on the governmental institutions of others seemed so high, and the means put at the disposal of achieving these ends appeared so brutal, that a doctrine that once had looked forward to undergirding world peace now seemed to have transformed itself into one destined to promote perpetual war. To be sure, Wilsonianism had always had American security as its primary concern, and many in Latin America especially had always felt that the call for democratic governments there served as a pretext for Washington to intervene in their affairs. This regional perspective now began to be more widely shared. How ironic that the ”neo-Wilsonianism” of the years after 9/11 had put aggressive self-interest so high on the American agenda that what had once been an anti-imperial framework for world order now threatened instead to become an imperial framework in its own right.