The independent Republic of Sudan emerged in 1956 after two phases of colonial rule—the Turco-Egyptian (1820-1881) and Anglo-Egyptian (1898-1956) periods respectively—and as a result of encounters with two competing powers, namely Egypt and Britain.

NINETEENTH-CENTURY COLONIALISM

Under orders from Muhammad cAli, who carved out an autonomous dynasty in Egypt under nominal allegiance to the Ottoman Empire, Turco-Egyptian armies invaded in 1820 the region that is present-day northern Sudan and consolidated control from Khartoum. Eager to secure new sources of military manpower, the Turco-Egyptian regime tapped into an escalating local slave trade by seizing male slaves for the armies of Egypt and by allowing private traders to sell females and children in northern Sudanese, Egyptian, and Arabian markets. The regime also forced the development of a Sudanese cash-crop economy and extracted taxes from the free population. At its peak by 1880, the Turco-Egyptian regime had a sphere of administrative and economic influence that extended to the Red Sea in the east, to Darfur in the west, and into parts of what is now southern Sudan.

British influence began to creep into the Sudan in the third quarter of the nineteenth century, when Britain was already flexing its political and economic muscles in Egypt. In the 1870s, the Egyptian ruler Khedive Ismail (a grandson of Muhammad Ali) appointed several British and other English-speaking military officers to the Sudan and entrusted some of them with suppressing the slave trade. This last measure was part of an effort to satisfy Britain’s antislavery foreign policy in Africa. In the 1870s, Khedive Ismail also attempted to assert Egypt’s presence in northeast Africa by deploying armies in the regions that are present-day Eritrea and Ethiopia. However, these plans for Egyptian imperial expansion crumbled after Egypt went bankrupt in 1876 and yielded to British and French financial regulation.

Six years later, in 1882, Britain occupied Egypt and placed the country under its own imperial subjection. In the decades that followed, Egyptian nationalists struggled to remove British control over Egypt even while continuing to press Egyptian claims to Sudan—a situation that prompted one historian to call Egypt in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries a country of ”colonized colonizers.”

By the time Britain occupied Egypt in 1882, the Turco-Egyptian regime in Sudan was already fighting for its survival. One year earlier, a Sudanese Muslim scholar named Muhammad Ahmad had declared himself to be the mahdi, a millenarian figure who according to popular Sunni Muslim thought would restore order at a time of chaos and repression prefiguring Judgment Day. Muhammad Ahmad, the Mahdi, rallied support among many Sudanese Muslims by condemning what he described as the un-Islamic practices of the Turco-Egyptian regime, notably their excessive taxation, their appointment of Christian military officers, and their efforts to end the slave trade (which Sudanese Muslims then regarded as a practice sanctioned by Islamic law). The Mahdi’s movement, in short, was a kind of anti-colonial jihad (Muslim holy war) that succeeded in defeating Turco-Egyptian forces in a string of battles after 1881.

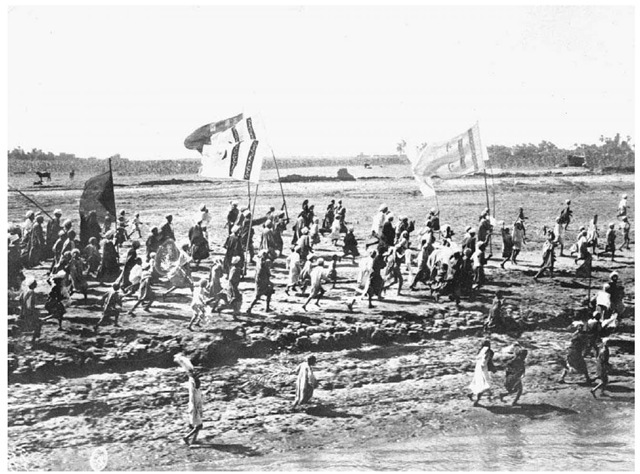

Riots in Sudan, 1924. Anti-British protestors run along the banks of the Atbara River in Sudan on September 1, 1924. Troops and ships were rushed to the scene to quell the disorders.

At the decisive battle for the city of Khartoum in 1885, Mahdist soldiers killed the British general, Charles Gordon, who had gone to evacuate the city. A decade later, when the European powers were pursuing their Scramble for Africa, memories of Gordon’s death in Khartoum helped to rally popular British support for the colonial invasion of the Sudan, set out to destroy the Sudanese Mahdist state (1881-1898) that had supplanted the Turco-Egyptian regime.

THE ANGLO-EGYPTIAN CONDOMINIUM

In 1898 Britain justified and bolstered its claims to Sudanese territory and thwarted competing French interests in the region by declaring that its invasion had been a “Reconquest”: a shared British-Egyptian effort to reassert political claims that the Mahdists had usurped. Britain went still further in 1899 by framing the new colonial regime as an Anglo-Egyptian “Condominium” in which Britain and Egypt would be co-domini, or joint rulers. To reinforce the Sudan’s special status, Britain refused to call the country a colony (akin to say, Nigeria or Hong Kong) and placed the Sudan under British Foreign Office rather than Colonial Office supervision. In reality, Britain dominated the Sudanese government. In the first half of the Anglo-Egyptian period Egyptians nevertheless made their mark on the colonial regime both in the army, where they served as officers, and in the bureaucracy, where they functioned as accountants, clerks, and educators.

Beginning in 1919, a year of nationalist revolt in Egypt, Britain became increasingly concerned about Egypt’s capacity to inspire anticolonial, that is, anti-British, sentiment within the Sudan. These concerns reached a climax in 1924 following a spate of urban anticolonial activities in the Sudan followed by the assassination in Cairo of the Sudan’s British governor-general. Responding to this crisis, Britain expelled the Egyptian army from the Sudan and fired or retired Egyptian bureaucrats in the Sudan. By 1930 the British had replaced almost all Egyptian employees with young, educated northern Sudanese men who were members of a nascent nationalist class.

In the second quarter of the twentieth century Egypt continued to insist on its rights to the Sudan even while struggling to reverse its own subjection to British imperi-alism—a subjection that remained palpable notwithstanding Egypt’s official “independence” in 1922. Ongoing frustrations over Egypt’s status in the Sudan sharpened nationalism in Egypt. Meanwhile, within the Sudan itself, nationalism was coming into focus among the educated northern Sudanese who closely followed and admired Egyptian popular culture as manifest in newspapers and poetry and increasingly, too, in movies and songs.

Despite these cultural ties, political sentiments toward Egypt varied among budding Sudanese nationalists. Whereas some insisted that Sudanese identity was distinct and autonomous from its Egyptian counterpart, others stressed the political and cultural affinities between Sudanese and Egyptians (even while rejecting Egyptian paternalism). These two camps of early Sudanese nationalism—represented by the slogans Sudan for the Sudanese and Unity of the Nile Valley respectively— came to dominate the local political scene in the late Anglo-Egyptian period.

DECOLONIZATION

Many of the political dramas of the immediate post-World War II years in the Sudan revolved around the questions of when and how Britain would devolve political authority on Sudanese nationalists (who were pressing for a greater role in local government) and what Egypt’s future status in the country would be. The situation became clearer after the signing of the Anglo-Egyptian Agreement of 1953, which set out plans for parliamentary elections in the Sudan and acknowledged the right of the “graduates” (that is, members of the educated class who enjoyed exclusive suffrage at this time) to decide whether to unify with or separate from Egypt. Sudanese parliamentarians ultimately chose separate autonomy. Thus the Sudan gained independence on January 1, 1956, barely six months after the start of a civil war that went on to blight the country during most of the late-twentieth-century postcolonial period.

Meanwhile, in 1956 (four years after the Free Officers Revolution of 1952), Egypt entered the final phase of its own decolonization as British troops finally withdrew from the Suez Canal zone. A few months later, the Nasser government nationalized the Suez Canal, an event that precipitated the Suez Crisis. Historians suggest that the Suez Crisis confirmed the demise of British and French colonialism in the Middle East and ushered in the cold war era of U.S.-Soviet regional dominance.